This article discusses the opera — or rather the “Play with Music and Pageantry” — Njinga by IONE and Pauline Oliveros. It extends understanding of Deep Listening through their joint work, considering in particular their treatment of historical narrative, and reflects on the philosophical implications of this, drawing on writings by Hayden White and Catherine Malabou. The operatic mode of Deep Listening in Njinga is presented as a praxis that addresses the historical trauma of enslavement and its continuity through forms of coloniality by composing conditions for the emergence of ancestral subjects touched by the passage of knowledge and affects across time and space.

“Those who are dead are never gone, they are there in the thickening shadow.”1

”For me, this is ancestor reverence at work.”2

Pauline Oliveros may be a familiar name to many readers, in particular through her practice of Deep Listening (DL) and the algorithmic text scores — notably the Sonic Meditations (1970–74) — through which it is best known. Her reputation is also established as a pioneer of composer-led free improvisation, DIY tape and electronics, Post-Feminist and Queer practices, and telematics — what we all now use with Zoom and MS Teams, she was doing a decade before the World Wide Web. Her ritualistic, theatrical, and operatic work may then come as a surprise. There is little written on it, including by Oliveros herself. Their appearance beyond the US has been rare, and their documentation and scores are not readily available. So whilst she has acquired legendary status for many, this is without knowledge of a significant body of her work. This article aims to address that imbalance.

I also intend to raise further awareness of IONE, Oliveros’s creative partner, performing collaborator, and spouse. Not only did she instigate their operas together; she wrote, directed, and often performed their texts. This raises two issues. First, as DL was not simply one aspect of Oliveros’s work but the name for an all-encompassing mode of creative practice, the operas should be understood as consistent with its principles.3 A core concern of this article is how DL addresses storytelling through opera, and especially how it affects historical narrative. I build on Colleen Renihan’s The Operatic Archive: American Opera as History, which examines ways in which operas by US composers since the 1990s have treated historical subjects not only by representing them on stage but by enlivening or reliving them, using music’s power to evoke memory and feeling.

Second, whilst DL is attributed to Oliveros alone, it is better understood as a life practice operative at all times, both awake and asleep, a practice that was not proprietary but informed by her work with others, above all by her relationship with IONE.4 I will focus on Njinga: The Queen King: The Return of a Warrior (1993), their first opera — or rather, “A Play with Music and Pageantry” – which gives voice to Njinga’s story as an African leader combatting colonial incursion, a phenomenon not yet consigned to the past but treated here as a decolonial task of re-membering or threading the past with the present. DL is not only a discipline of personal meditation, here, but a political practice dealing with injustice. In Oliveros’s words, “One of the things we want to do according to my partner and co-Deep Listening teacher Ione is ‘make peace more exciting than violence.’”5 What emerges from this article is, I hope, both a more nuanced understanding of DL and a potent means of engaging historical injustice in the present with contemporary politics of the past.

We immediately face a problem doubled: neither the opera nor the history it conveys are finished, complete, or discrete objects. The history of the opera and the history in the opera are open, incomplete, porous. Njinga was not fixed definitively in full score but was constitutively in process. Oliveros and IONE were concerned with the performance context, being especially attentive to audiences as agents in the production of meaning, and adapted pieces to given circumstances.6 Furthermore, it is not a “work” in the sense of an intentional object but, in keeping with DL principles, a collaborative endeavour. Alongside IONE’s text, choreographic direction was led by Carol Chappell, and the music has multiple credits: Titos Sompa for traditional Congolese music, Nego Gato for traditional Brazilian music and dance, in addition to Oliveros’s original music and sound.7 Whilst the DVD recording of its first performance at Brooklyn Academy of Music provides a useful reference, then, it does not and cannot tell the whole story.8 Any attempt to claim Njinga’s definitive meaning would be misleading. Drawing on interviews, I therefore emphasise its development process in order to appreciate the formal logic by which it constitutes meaning as emergent in performance.

This approach is consistent with how the opera addresses its historical material, one that can be understood as decolonial, following critiques of the coloniality of Western historiography. Aníbal Quijano, for example, registers the violence implicit in history conceived as an object, singular, especially when written as the continuous narrative of a “macro-historical subject” endowed with intention.9 As I will show, Njinga elaborates a heterogeneous history, a narrative comprised of differences that resonates with Hayden White’s presentation of “the practical past” in artfully presenting past and present knowledge in ways that can disposition audiences and reorient action.10 In short, the processual composition of the opera materialises the past within the present so that it is not a closed book but a writing still being written, in bodies, hearts, and – provisionally – on the page and the stage.

My own history with Oliveros and IONE also affects this text. I have been privileged to work with them, featuring Oliveros’s work in a festival I curated in Birmingham in 2014, attempting to secure European performances of their last opera, The Nubian Word for Flowers, delivering with IONE a performance lecture on Oliveros’s legacy in Athens for documenta14, and contributing a text for the 50th anniversary edition of the Sonic Meditations. In keeping with DL, in which there can be no outside position from which to observe the experience — the musical and aural contrast with visual distance is notable — no separation or sitting in judgement, my aim is rather to unfold the logic at work in this “operatic” mode of DL with its musical and philosophical implications. What matters with Njinga is not what it means but how it produces meaning as an historical event.

I begin by introducing DL through Oliveros’s collaborative and operatic work in order to present its formal logic, then introduce IONE both to describe the emergence of Njinga and to relate the way that DL, as a practice of expanding consciousness, affects and is affected by the past. By unfolding the creative process of making this opera, I aim to account for DL as a praxis — or logic through application — so that its production of meaning through performance, as an event, becomes clearer. DL intervenes through dream and memory, I will argue, without the repetition of trauma.

Oliveros’s work in theatrical and expanded performance pre-dates the Sonic Meditations and DL. In San Francisco, she was part of a community of artists who created their own DIY spaces. Alongside musicians and composers, there were the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Actor’s Workshop, Anna Halprin’s Dancers’ Workshop, and the Open Theater. Oliveros collaborated with many of them: “works with A.A. Leath, Lynn Palmer, and Norma Leistiko were called operas and were generally absurdist in nature.”11

In the experimental spirit of the late 1950s, music was rarely “absolute” — a supposedly pure concern with sound and form — but increasingly engaged with the performance situation and context as a whole, including performers’ gestures, costume, space, site specificity, stage design, audio-visual technologies, and especially the nature of audiences. It was in this sense that Cage’s work was famously charged with “theatricality” by the art critic Michael Fried.12 Or as Cage pithily put it in “Composition as Process,” “an ear alone is not a being.”13 In a similar vein, we might say that DL is not only an ear-based discipline, and Oliveros’s work was often theatrical in this mode of expanded performance.

Perhaps her most elaborate staged work of the time, Pieces of Eight (1964) was written using instructions rather than notation, specifying

virtually every aspect …, from the costumes, props, and staging to the performers’ actions, including their emotional attitudes and breathing. The score calls for wind octet and a large selection of props, including a cuckoo clock, eight alarm clocks, a papier-mâché bust of Beethoven with blinking red eyes, a cash register, a tape of bird sounds, ticking clocks, telephones, and an organ. The performers dress as plumbers, pirates, priests, and other bizarre characters. Based loosely on Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Pieces of Eight resembles early twentieth-century performance art such as the futurist “variety theater” or, as one critic observed, the theater of the absurd.14

These experiences showed her that conventional music notation not only limited compositional possibilities but also constrained the mode of collaborating with artists in this expanded form of performance. She turned to her “automatic writing” of doodles and visual puzzles, finding a kinship with mandalas, and saw this as a means to create form that had compositional logic — “an organizing principle”15 — that remained open to the initiative of collaborators. Pieces of Eight was the first outcome. In addition to the humorous nod to Treasure Island, the piece made multiple puns of the number eight, stemming from the mandala form she adopted, a circle divided into eight parts shaping the connections between different elements.16

By the mid-1970s, as she explored expanded consciousness through scientific, spiritual, and creative means, Oliveros was awarded a Fellowship to study ritualism in “American Indian music”. This bore fruit with Crow Two: a Ceremonial Opera (1974). Commemorating her grandmother following her death, Crow Two was formed as “a human mandala” A central “Crow Poet”, “a beautiful woman of seventy with silver gray hair who sits smoking and dreaming”17 is surrounded by four “crow mothers”, encircled by two dancers, and a further ring comprising seven drummers, rock players, and others meditating. Beyond them sit didgeridoo players and Heyokas or “sacred clowns” from Lakota culture who aim to distract the meditators, with the audience enclosing the whole (Figure 1).

Tara Browner accuses Oliveros of “whiteshamanism”, of misappropriating Lakota culture by drawing from ethnopoetics rather than by learning directly from Lakota people, and in particular of incorporating Heyo’ka within a mixture of spiritualities and nativist traditions — anticipating a later critique of appropriation in Njinga.18 I will address this claim in a further essay, but note here that this is based on a binary opposition that misses how the piece operates.19 It was not what the Heyokas “mean” but how they produce meaning that is key here. The piece is a meditation on meditation, understood as a capacity to balance conscious and unconscious processes.20 The Heyoka interjections provide a necessary disequilibrium and discontinuity offsetting the different durational, drone-like and intuitive meditational forms of the other performers, and it is this interplay of attentional modes within a field of associations prompted by the “Crow” in its symbolic diversity that is designed to affect meaning as both singular — what strikes the individual — and collective.

The mandala form operates as a “psychogram” allowing for “psychosonics”, in Heidi von Gunden’s terms.21 Oliveros began to appreciate the mandala as a “spatial orientation,”22 a specific conjunction of times, places, and people comprising the encounter and constituting its meaning. “Mandala time is based upon the principle of synchronicity,” von Gunden claims; “events do not develop in the Western sense of linear cause and effect.”23

Jann Pasler has elaborated some key implications in an article using an interview with Oliveros contemporaneous with Njinga’s production (1993).24 First, she correlates this temporal “orientation” with the spatialisation of historical time described by Fredric Jameson.25 In brief, if modernist sensibility in the wake of Hegel traced time as a line progressing purposefully from past to future through dialectical negation, postmodernity marked its rupture and dissolution. Historical time did not now advance so much as it “spread”. This is not the place to detail all the problems of this “post”, “lateness” or afterlife of modernity, but it is neatly summarised for our purposes in John Cage’s analogy of music history as a river (the canon, say) that had turned to a delta and was now becoming ocean.26 Distinguishing musics and then historicising them in their lineages, what Susan Buck-Morss critiques as a vertical slicing through history27 — as though taking a sample from the ocean and distinguishing how much comes from different source rivers — becomes increasingly problematic. Musical time no longer progressed in the avant-garde sense of advanced techniques, always pointing beyond itself, but concerned the temporal mode of its experience. This time was not only phenomenological, in the way that “time” has been treated as distinct from “history”, but also and simultaneously symbolic.

As music no longer progressed stylistically or dialectically, the role of past musics became more prominent. Musical postmodernism then seemed obsessed with citation and collage, composed of fragments of its past. However, synchronic time conceived spatially is not a question of continuity or discontinuity — of forward motion or past reference — but of links within a network. In this way, music offered ways of connecting different times and places by acting as a form for relating, and specifically of engaging an audience’s collective memory.28 Jameson had likened the problem to “cognitive mapping” — the capacity to make sense of the world in the way that you might know your way around town — which in the alienating “modernist city” had begun to dissolve. In a world become fluid, oceanic, without fixed reference points, we can easily become disoriented.

Pasler then ventures that practices like Oliveros’s afford a reorientation. Mandala time, in other words, is not a structure in which one thing or one sound necessarily follows another from beginning to end, but a means of organizing the presence of many times simultaneously — the social time of memory and imagination, the historical time of the performance site and context, as well as the phenomenological time articulated through the event. In Oliveros’s words (cited by Pasler)

It’s being aware in the moment and being able to reflect upon it, being able to reflect on what has happened rather than theorizing. Dealing with what is,” … rather than setting up a thesis in advance and projecting into the future. If there is a frontier in music, she says “it's relationships, and collaboration, and an aesthetic arena that is developed in performance.29

Oliveros gave a remarkably succinct account of this through what might be considered the fundamental mandala of DL, a circle with a central dot — although the two-dimensional printed circle should really be understood as a sphere (Figure 2).30 We can allow our attention to dilate, to open so that it receives all sound in the field or, crucially, to tune into memory and anticipatory imagination (or auralization)31 along with others. This is the sphere. However, we can also constrict our attention by focusing on one sound, a fine point, which a performer can channel for us. In this way, attention has “a tuneable range”; von Gunden describes Oliveros tuning attention and awareness “much as if these functions of consciousness were potentiometers on an oscillator.” In her mandala-based performance pieces, audiences are immersed in a space of memory, myth, and of multiple times and places. The aim is not to represent time but to affect it meaningfully. For Oliveros,

Listening is a process. It can be like a bolt of lightning all at once in the moment or it consists of good intuitive guesses and thoughtful references to past experience. Raw listening has no past or future. It has the potential of instantaneously changing the listener forever. It is the roots of the moment.32

Performance, theatre, ceremony, and — with IONE — opera extended DL practices to address connections in symbolic time, shaped collaboratively, that does not “advance” or “climax” but that can swell and surge. In Njinga and their other four “operas” — the Lunar Opera (2000), the “dance-opera” Io and Her and the Trouble with Him (2001), the Taoist performance piece Oracle Bones, Mirror Dreams (2009), and the “phantom opera” The Nubian Word for Flowers (2006–2020) — the spark and energetics of this potential came from Oliveros’s relationship with IONE.

IONE, whom Oliveros met around 1984, is a writer, poet, playwright, performer, and psychotherapist specialising in myth, heritage, dream phenomena, and women’s issues. Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, her 1991 landmark memoir, traces resonances through time via her mother Leighla, a journalist, writer of murder mysteries, and Calypso composer; her grandmother Be-Be, a stage dancer in Black vaudeville and the Harlem Renaissance, whose partner Leigh Rollin Whipper was a founder of the Negro Actors Guild of America; and his extraordinary mother, Frances Rollin Whipper, a writer, political activist campaigning against slavery, segregation, and for women’s suffrage in the pre- and post-Civil War southern US. Writing under a male pseudonym, “Frank” Rollins wrote the first full-length biography written by an African American, published in 1868, on Martin Delaney, the abolitionist, nationalist, and highest ranking Black commissioned officer in the Union army. She also won one of the earliest Civil Rights lawsuits after being denied first class passage on a steamship traveling between Beaufort and Charleston, South Carolina.

This lineage accounts for IONE’s interest in the musical stage: Be-Be took her to Broadway shows — indeed, IONE herself appeared in Show Boat when it was revived in 1946 — and her mother performed her music at Radio City Music Hall.33 For IONE, however, this is not only family history but a well-spring of knowledge and spiritual understanding that inhabits her. Inheritance is not simply genetic coding for, say, blue eyes or short height. It is also symbolic, material culture that incorporates familial and collective memory accessible through dreaming consciousness.34 We might say that cultural memory is already present in the womb. This is why intuition, dreaming, writing, and other creative practices provide access to ancestral being that can, IONE says, be healing.

The sense of connection between IONE and Pauline goes both ways, not as a transfer from one to the other so much as a resonance with the other’s being; separating out where the contribution of one begins and the other ends is neither possible nor meaningful. Whilst IONE’s enthusiasm for the musical stage led to their many creative collaborations, she also pursued listening in dreams as her particular specialism.35 Like Oliveros’s account of DL, this practice is also concerned with emergent phenomena — visitation dreams, musical inspiration, connections across times, out of body experiences, and psychic connection — that swell and surge between attentional states, especially those of aural awareness during sleep and listening within dreams, and the hypnoidal movements between sleep and wakefulness.36 Her creative vision

is to explore the transitions and connections of moving from dreaming life to waking life, of moving through various forms of consciousness by contemplating sleeping dreams as well as body/mind experiences of conscious/waking dreams, and to “project” these experiences through creative performance.37

One such dream was of Njinga Mbande, who ruled as Ngola (leader) the Kingdoms of Ndongo and Matamba — in present-day Angola — from 1624 until her death in 1663. It was through her father that IONE first encountered a defining image of Njinga.38 Prof Hylan Garnet Lewis (1911–2000) was an eminent sociologist, celebrated for Blackways of Kent (1951), his participant-observer account of African American life in a small Southern town prior to the civil rights era. His work also included a prominent role as an adviser for the Volta River Project in Ghana (1956), Kwame Nkumrah’s thwarted plan to decolonise the country through domestic industrialisation.39 In the engraving, Njinga meets the Portuguese colonial Governor João Correia de Sousa in 1622; offered a floor cushion, she refused this submissive position and instead used the back of her servant to sit as an equal, at eye level with her adversary (Figure 3), a scene that appears prominently in the opera.40

As a canny diplomat and courageous warrior, Njinga resisted colonisation and especially the expanding slave markets, earning her a disputed posthumous reputation.41 For Europeans, she came to embody a racialised, gendered, primitive Other, a deviant, treacherous, corrupt and hypersexual leader, unable to control her desires, who was rightfully subdued. Daniel Silva notes how, by having male concubines, she provided a model for French libertine writers in the late 18th century, such as Jean-Louis Castilhon and the Marquis de Sade. Significantly for what follows, Hegel used her reputation implicitly — he indicated her story but renders her unnameable — in his argument positing History (i.e. history as such, Quijano’s “macro-historical subject”) as the reflexive narrative form of a European male subject; colonised peoples, especially women, were not subjects in this sense at all.42

For Angolan and wider African independence movements, however, Njinga became an icon of righteous resistance and an inspiration for anti-colonial struggle. Agostinho Neto, then leader of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and later the first President of independent Angola, wrote a poem on her in 1960, initiating a move to present Njinga as a heroine and rallying figure for MPLA-aligned nationalism that continues today, for example with the 2013 film Njinga: Rainha de Angola.

Silva argues that in contrast with this political reclamation of her story, which tends either to reproduce colonial emphasis on the “primitive” state of Njinga’s culture or modernises it anachronistically for modern moral or political tastes, she has been inspirational for diasporic moves towards a deeper dismantling of Empire. Rather than making her an historical subject, contra Hegel but within the same historiographical form — a problem Hayden White diagnoses in terms of what constitutes an event as legitimately “historical” — poems such as “Song of Love and Respect for Queen Ana de Souza” (1978) (using Njinga’s baptismal name) by negrista Georgina Herrera entailed a “ounter-hegemonic renegotiation and reinvention”.43

We can push this further by considering Black women in historiography. To counter their erasure from history and from the writing of history, as “their stories have been either untold or mistold”, Paula Sanmartín argues that Afro-American and Afro-Cuban women writers have incorporated themselves and their own lived experience in “seiz[ing] discursive control of their (hi)stories”.44 By creating ‘a “literature of fact” with which … to counteract a “history of fiction” in order to ensure the “correct” representation of black women in historiography’, Black women authors have constituted performatively the subject-voice of Black women historical figures in the present.45 White draws similarly on Toni Morrison’s account of her novel Beloved — as a self-declared exercise in the “philosophy of history,” by voicing its historical central figure Margaret Garner to bridge past and present — to elaborate a key aspect of “the practical past”. This addresses the past as a social practice of world-making, or (re)orienting time, which he contrasts with ultimately futile attempts to ground historiography “scientifically”.

For our interest in the practical past must take us beyond “the facts” as conventionally understood in historiological thinking. Indeed, it must take us beyond the idea that a fact…is identifiable by its logical opposition to “fiction”, where fiction is understood to be an imaginary thing or product of the imagination.46

History speaks in the present through the voices of those excluded by historiography.

IONE first wrote on Njinga in the mid-1970s with the aim of publishing in the feminist magazine Ms, where she was a contributor, but as it was declined she eventually saw it printed in the Village Voice in 1980.47 Reflecting back on the journey from this to the opera, IONE said,

The article would not come unless I wrote it in the first person. I was trying to write a third person article about this woman, but I couldn't. It just wouldn't come alive until I began to, in essence, bring her through me, through the dream time. So I did that. And as I say, when I looked at the article, I thought, gee, this is really a play.48

This is staged in Njinga, where the Journalist, a young Black woman who bridges this ancestral past by writing about it and so discovers — and so becomes — who she is, begins typing her account of Njinga’s diplomatic encounter with de Sousa, changing her third person into a first person narration.49

As IONE’s relationship with Oliveros blossomed in the late-’80s, they began performing together. Oliveros improvised as IONE voiced her texts, then gradually bypassed the written page and improvised in ways that were neither exactly spoken word poetry nor performance poetry.50 It was a short step to creating the opera together. With Njinga, then, IONE and Oliveros staged the disappearing of Black women as historical actors in the conventions of historical narrative. They did not aim to set the record straight so much as to queer this (hi)story itself, using dream consciousness to (make) present this ancestral subject through music, dance, and performance.51

At first, Oliveros was terrified by the idea of creating this opera, in particular the risk of being perceived as a white composer appropriating African culture.52 After a long period of meditating on it, her solution was to create a composition on three levels. On the first, in a manner typically ahead of her time, field recordings from Angola and the New York subway provided a soundscape for different scenes using a spatialised speaker array with delay processors — a “Portable Virtual Acoustical Environment” — to simulate their acoustic spaces.53 Her own music, second, provided “atmosphere and a kind of emotional comment and host” for traditional music related to Angola at the third, “so that these could remain independent in the environmental sound, the traditional music, and my own music, and yet interact”.54

This prompted an intensive process of research. Oliveros’s friend Carol Chappell, who had studied African drumming and dance with traditional masters since 1975 and was teaching in the same studios, introduced her to Nego Gato (and later to Titos Sompa).55 He encouraged Oliveros and IONE to make a field trip, in 1990, to Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, where a substantial Angolan diaspora — forcibly displaced by the slave trade that underscored Njinga’s (hi)story — had maintained and modified their traditions. Hosted by his family, they attended a Candomblé ceremony — the syncretism of African religions with Catholicism, by which saints corresponded with African deities — and learned about Capoeira Angola from masters of this dance form that slaves had used to disguise the modes of fighting denied to them, “to maintain their prowess”.56

They began building the opera through workshops, first at the Yellow Springs Institute in Chester, near Philadelphia, then later in Lisbon and at Chappell’s studio in Woodstock. Sessions would begin by forming a circle, expressing feelings, and practising listening meditations guided by Oliveros “to get [their] energy connected and then proceed from there.”57

IONE’s initial idea of a “minimal play” for perhaps six people playing multiple roles began to expand, nowhere more so than in their production for the Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, in July 1993. Whilst preparing this, IONE delved into the local archives and found slave ledgers — read out in the production — and she and Oliveros were introduced to a descendant of Njinga who had some of the Ngola’s artefacts and was able to pass on what she had herself learned from her elderly grandmother.58

IONE “designed the show so that [they] could always invite local people in”, and having adapted the script specifically for the Portuguese context was then amazed by the response.59 Still living this (hi)story, over 80 diasporic Angolans from the quartieros, “walled in” districts of Lisbon — many from Luanda, the harbour city from which slaves were shipped — auditioned and took part, much to the Theatre administration’s consternation. “Every time we went into the theatre, we were creating a whole world”, a phenomenon that earned her the nickname Cecil B. IONE, after the pioneer of epic historical films, Cecil B. Demille. Over 800 came for the performance in Lisbon

and the entire audience just completely went wild as [Njinga] points to her servant and has the servant go with all fours and that she can sit and have an appropriate seat to converse with the governor. The moment that everyone went crazy because they knew that was their history in Lisbon. And it was a powerful moment for the Africans, for the Angolans.

It is important to note how this mode of production was both necessary to enable Njinga’s hi(story) to inhabit the stage with and through its performers, rather than simply to be represented, and disconcerting for institutional norms, not least in its technical demands, participatory ethic, and its appeal beyond their regular audiences. Promoters, funders and other partners approaching the project through issues of representation struggled to understand and accept its multicultural (and lesbian) creative team.

The play is about … the encounter of two very different worlds, the Portuguese and the Angolans… . And what we discovered as we were both creating the piece, and it would go into a theatre with our multinational cast, was that we were replicating that encounter. And so the theatre had to deal with us and find out some things about themselves and about us coming in. And it was never easy.60

Constitutively open to local collaborators and especially to audiences, we can see that Njinga developed as a praxis combining research and creative collaboration. This mode of investigation and composition is itself then staged by the opera. The Journalist acts as a kind of Greek chorus whose research into this (hi)story both contributes to the plot’s narration and simultaneously enacts a process of self-discovery. As she listens to her dreams, she brings the practical past into the living present to find it resonating in both her body and her political present — a third “plot” staged in counterpoint with Njinga’s and the Journalist’s concerns Operation IA Feature, the CIA’s covert effort to defeat the anti-colonial MPLA forces governing Angola, as well as the Agency’s involvement in the assassination of the Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba. Oliveros’s composition then supports this movement between times past and present, as we will see.

This account of Njinga resonates with and supplements Renihan’s argument, in The Operatic Archive, that the turn to historical (and recent) subjects in opera from the 1990s can best be approached through the ways that history has itself been reconceived, especially from the 1970s. In recognising the problems of history conceived as a mode of writing, the aim of scholars and artists alike has been “to broaden understandings of history, to de-centre history, re-humanize it, and re-shape it in light of new realities of citizenship, memory, and story-telling”.61 Her study draws particularly on operas dealing with experiences of war and trauma; Njinga approaches this through similarly traumatic and ongoing experiences of racism, chattel slavery, and colonialism, using DL.

IONE and Oliveros’s work is not the only opera featuring an African queen, but it is the first to present her own voice. The Carthaginian queen Dido is perhaps the best-known precursor, as portrayed through tragedy by Purcell and Berlioz, though her Blackness is erased in these works. In contrast, the race of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine is pivotal to the plot. Bought in a Madagascan slave market, this “Indian” queen becomes the amorous foil for the opera’s hero, the Portuguese colonial explorer Vasco da Gama. The theme of slavery is largely passed over in silence, compared with religious bondage, or sublimated in devotion. Its politics are Orientalist, conveying the impossibility of inter-racial love to preserve “the dignity of the Romantic hero and a hero of European colonial enterprise”.62 Grand opera may have introduced historical figures to the stage to appeal to the emerging historical (and national) subjectivity of European publics, yet this was not to be a place for Black women.63 If opera has been a vehicle for expressive interiority, its vocal subjectivity has been premised on its whiteness. It is indicative that when William Grant Still’s Troubled Island (to a libretto by Langston Hughes and Verna Arvey), on the Haitian revolution, was first produced by New York City Opera in 1949, the lead characters of Jean Jacques Dessalines and his wife Azelia were sung by white opera stars in blackface.64

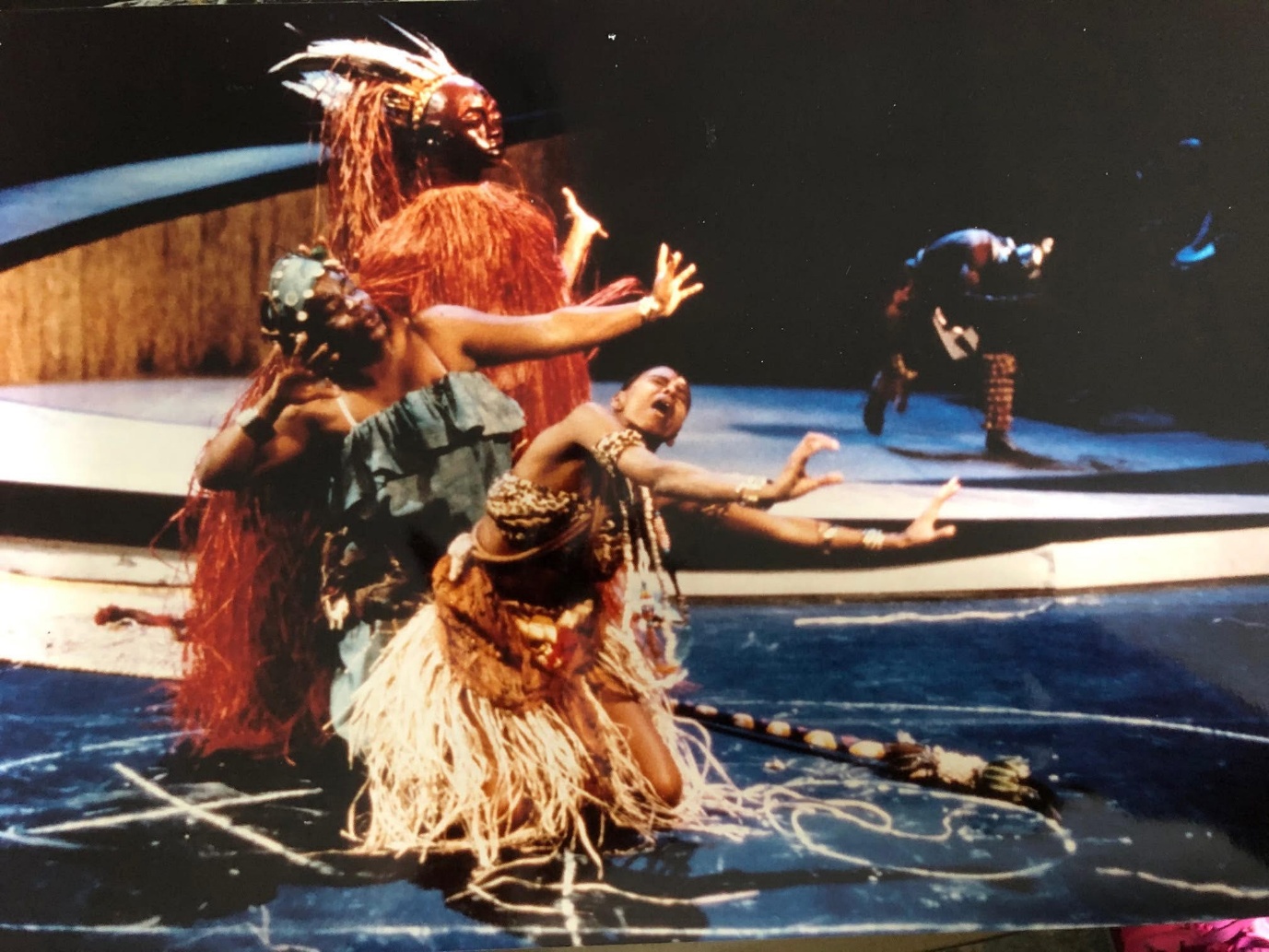

Oliveros and IONE bring Njinga’s (hi)story to life, then, not simply by granting her an inner life but by altering the nature of the subject from which it is voiced. Njinga’s story is voiced variously by the Journalist, as a disembodied and dream-like ancestral voice, and is performed — and spoken in her native tongue, Umbundu — by three dancers portraying episodes from different stages in her life and ancestral afterlife, who even appear together on a mandala drawn onto the stage (Figure 4). This subject is multiple, both historical and present, and conceived as such by IONE.65 Indeed, both the journalist and Njinga are encouraged and guided by ancestors who “haunt” the fringes of the stage as “ghostly figures in traditional costumes…[dancing], silently observing and affirming”.66 The dreamworld of their appearance, telescoping times and places, is between the stage-light and stage-darkness, the hypnoidal space that both troubles the Journalist and gives her confidence: “Oh Shadows! I can’t sweep them out of the corners”.67

This ancestral subjectivity is also not only vocal but corporeally present through dance, a key feature of the pageant. As Chappell explained,

dancing is the story. It's not merely used to tell the story, but it becomes part of the way of life and the way an African person expresses themselves … . Music gives life to the dance. The spirit leaves the drum, goes into the earth, and enters into the body of the dancer … . And that's where the spirituality comes in, that share of energy between the drummer and dancer.68

From reports of multiple productions, the dancing did not remain on stage alone. In Washington DC, for example, IONE arranged for the African dancers to process along the aisles and through the audience.69 At an outdoor performance at New York’s Lincoln Center in 1995, some of the audience, “dominated by African-American women[,] … joined in the dancing at various points throughout the performance”.70

For IONE, this was an expression of the opera’s ancestral subject presented through dream consciousness. Njinga’s

first visions come in dreams. Her first breakthroughs are in the future and past … . And in dream time, we connect to what might be called in other cultures the spirit world. So, it's very important that we have this connection in play. So, I feel that the audience itself will be feeling very much as though they were in a dream when they're in the theatre. That's my goal.71

Oliveros’s compositional approach, the sound design and music are all productive of this dreaming state and its power of connection across time and space. Angola, New York, and the Brazilian and Portuguese diaspora are interwoven not as sonic signifiers attempting a realist staging but as a plurality of embodied times opened to and capable of morphing with each other by resonating with the listening memories and imagination of the audience. Indeed, the “interaction with African musicians who also improvise with [Oliveros’] music at times for special effects” is most telling at precisely those moments where dreamwork unites the living present with those in the re-membered past.72 It occurs when the Journalist, reflecting on others’ comments that she “talks Black Talk” only with her grandmother, now dead, begins talking with her after a dream (Njinga, 8:40); when narrator-Njinga says that she “was a child when the dream began” (11:13); when the Journalist voices Njinga’s encounter with the Portuguese (1:04:45); most powerfully, when Njinga is taught to conjure her own ancestors through dream (35:52); and at the conclusion (1:45:10) when the Journalist reads a report of the uncovering by New York City Hall of the bones of a seventeenth-century African woman.73

It is through dreaming consciousness, then, that the politics of Njinga’s (hi)story plays out. Decolonisation is fought not only in the present, in the shadow wars of neocolonial “adventurism”, but also through Njinga’s rebellion in the past, and the interlacing of these struggles through the practical past.

Oliveros coined the term Deep Listening for this discipline in part as a pun, following her 1988 descent into the Fort Worden Cistern — a “two million gallon hole in the ground” with a 45” reverberation time — alongside Stuart Dempster and Panaiotis to record the first Deep Listening album. What has not been acknowledged is that this consolidation of DL occurred at precisely the time she and IONE began living and working together, contemplating and then making Njinga. We can approach DL without reading its genealogy and biography as singular. Similarly, the authorship of this piece was, like the (hi)story it stages, multiple, not only shared between them but extending to a host of collaborators, participants, and audiences, listening for and dancing with these ancestors in ways that stage an open process of collective and self-discovery through dreamwork, memory, and listening.

Njinga’s praxis engages the intertwining of past and present in ways similar to Toni Morrison’s characterisation of Beloved as a “philosophy of history”.74 White situates this alongside a shift in addressing the “historical event”. Events, he argues, traditionally became historical to the extent to which they could be incorporated in a narrative series, according them meaning and answering “to the central question of ethics: ‘What should (ought, must) I do?’.”75 This emplotment of events was maintained in nineteenth-century historical realist novels — like Tolstoy’s War and Peace — just as historiography was purified of plot in the name of scientific objectivity to constitute “the historical past”. Philosophers of history, however, were concerned with “divining general principles regarding the nature of human beings” existence with others in time’, and so also aligned with the action-orienting ‘practical past’.76 White then proposes that, in the wake of historical trauma — notably the Holocaust, 9/11, and the event of enslavement — the status of “the event” was itself changed, becoming a philosophical problem. As these occurrences could not be sequenced in the realist mode, postmodern novelists created literary devices to re-present the historical event otherwise, each constituting its own philosophy of history.77

In this sense, DL operates not only as a phenomenological framework for meditation but as a meaningful practice that composes events to heal historical trauma. We can contrast this approach with the Freudian logic of trauma, especially as it relates to postcolonial experiences of the event of chattel slavery. As Catherine Malabou shows, trauma is a temporal wound, the product of an event that cannot be cathected, cannot be meaningfully incorporated within continuous self-narrative but creates a block to which the subject continually returns.78 Similarly, neocolonialism demonstrates that coloniality — to use Quijano’s term — never ended but continues to operate, to repeat itself. It is necessary but insufficient, then, to account for this (not yet) past of enslavement through historiographic norms because these are themselves colonial, as White elaborates through the ways that events were rendered “historical” by their detachment from the miraculous and from the practical pasts afforded by myth, “memory, dream, fantasy, experience, and imagination”.79

Malabou is similarly critical of the mythic dimension of Freudian trauma, famously the Oedipal logic whereby a senseless contingent event — at the crossroads of history, perhaps — can always be made meaningful by recourse to an earlier one (such as the subject’s abandonment or removal from its parents) that accounts for it. She contrasts this with the late modern phenomenon of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which indicates the presence of unexpected catastrophic events that refuse the reimposition of order, that cannot be reincorporated in self-narrative without introducing an inauthenticity in psychic life. The trauma “creates another history, a past that does not exist and, in this sense, constitutes a ‘neurotic imposture.’”80 PTSD cannot be healed by returning narrative to the subject because the event marks a discontinuity that changes the subject. It is the refusal to acknowledge this that ensures the continuity of coloniality by appearing to consign the experience of enslavement to the historical past.81

Suggestively, for us, Malabou refers to a distinction made by the military psychiatrist Claude Barrois, who contrasts the Oedipal with the Orpheus myth. “Traumato-neurotic personalities have returned from hell not from childhood. … . ‘Back from the land of the dead, the poet is no longer inclined to sing.’”82 Neither the Journalist nor Njinga sing in IONE and Oliveros’s play, but they do dance and connect through time. The Journalist does not recover her self-narrative but becomes a different subject, visibly changed through her ancestral past. Rather than curing through transference to a misleadingly “neutral” analyst-historian, the task now, Malabou argues, is to return feeling to the subject, to have compassion, becoming the subject of the other’s suffering “not to take his place, but to restore it to him.”83 In contrast to novelists, the Orphic event of opera affords just such an emotional connection.

This is precisely how Oliveros accounts for DL.84 It is also how IONE describes the processual composition of Njinga, whereby for history to be transformed, not repeated, it must be inhabited differently.

The purpose of the play is to heal. And one way to do that is to involve people who are in the local places with process. The process itself is a very healing process. It's a creative process of working on something like this to heal and to educate. This automatically extends the aura of the healing into the community. It creates a larger community. And that itself goes out into their families, their worlds, and hopefully continues to expand.85

Simply reclaiming Njinga’s (hi)story by giving her a narrative voice would leave colonial history intact. This play with music and pageantry is decolonial, then, in making other connections, rewiring the relations of past, present and future, and so opening onto other possible worlds.

“Ancestral Voices,” on Njinga the Queen King. Directed by Stephen Barnwell (1992; NY: Mode, 2010), DVD.

“Ancestral Voices.” Njinga the Queen King. Directed by Ione Lewis. New York: Mode Records, 2010.

Andrews, Jean. Meyerbeer’s “L’Africaine”: French Grand Opera and the Iberian Exotic. The Modern Language Review 102, no. 1 (2007). http://www.jstor.org/stable/20467155, 108–24.

Bernstein, David W. The San Francisco Tape Music Center: 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-Garde. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Browner, Tara. “They could have an Indian soul”: Crow two and the processes of cultural appropriation.’ Contemporary Music Review 19, no. 3 (2000): 243–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411890008574774.

Buck-Morss, Susan. Year 1: A Philosophical Recounting. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021.

Buck-Morss, Susan. Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. London: Marion Boyars, 1968.

Cavazzi, Giovanni Antonio. Istorica descrizione de' tre' regni Congo, Matamba et Angola: Situati nell'Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni apostoliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini. Vol. 5. Bologna : Giacomo Monti, 1687. urn:oclc:record:1047404784.

De Certeau, Michel. The Writing of History. Translated by Tom Conley. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

Chappell, Carol. Conversation with Ed McKeon. Online, December 1, 2024.

Fried, Michael. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Gunden, Heidi von. The Music of Pauline Oliveros. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1983.

Hegel, G.W.F. The Philosophy of History. Translated by J. Sibree. Kitchener, ON: Batoche Books, 2001.

Hibberd, Sarah. French Grand Opera and the Historical Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

IONE. Listening in Dreams: A Compendium of Sound Dreams, Meditations and Rituals for Deep Dreamers. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2005.

IONE. “Deep Listening in Dreams: Opening to Another Dimension of Being”. In Anthology of Essays on Deep Listening, edited by Monique Buzzarté and Tom Bickley. Kingston, NY: Deep Listening Publications, 2012, 299–313.

IONE, dir. Njinga the Queen King: The Return of a Warrior. Performed December 1993. New York: Mode Records, 2010, DVD.

Ione, Carole. Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color. New York: Harlem Moon, Broadway Books. New York: Drogue Press, 1991.

IONE. Conversation with Ed McKeon. Online, October 18, 2024.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991.

Kostelanetz, Richard, ed., Conversing with Cage. London: Omnibus Press, 1989.

McKeon, Ed. “After Words.” In Sonic Meditations, edited by Pauline Oliveros. Kingston, NY: PoPandMoM, 2022.

McKeon, Ed. “Listening Changing Itself: a Future for Pauline Oliveros.” Unpublished lecture, first performed with IONE at documenta14, Athens, July 13, 2017.

Malabou, Catherine. The New Wounded: From Neurosis to Brain Damage. Translated by Steven Miller. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012.

Oliveros, Pauline. Sonic Meditations. Kingston, NY: PoPandMoM, 2022/1974.

Oliveros, Pauline. “Auralizing in the Sonosphere: A Vocabulary for Inner Sound and Sounding.” Journal of Visual Culture 10, no. 2 (2011): 162–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412911402881.

Oliveros, Pauline. Sounding the Margins: Collected Writings 1992–2009. Kingston, NY: Deep Listening Publications, 2010.

Oliveros, Pauline. The Roots of the Moment. New York: Drogue Press, 1998.

Oliveros, Pauline. “Cues.” The Musical Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1993): 373–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/77.3.373.

Oliveros, Pauline. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2005.

Oliveros, Pauline. Software for People: Collected Writings 1963-1980. Baltimore, MD: Smith Publications, 1981.

Osborne Peter. The Politics of Time: Modernity and Avant-Garde. London: Verso, 1995.

Pareles, Jon. “A Tale of Africa’s Past That Haunts the Present”. New York Times, December 3, 1993), C 3.

Pasler, Jann. “Postmodernism, narrativity, and the art of memory.” Contemporary Music Review, 7, no. 2 (1993): 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494469300640011.

Kereszi, Victoria, IONE and Pauline Oliveros. “Peak Moments”. Njinga the Queen King. 2009. Directed by IONE. New York: Mode Records, 2010, DVD.

Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality and Modernity / Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2007): 168–78.

Ramirez, Eloy. “Queer Theory and Third-Wave Feminism in Pauline Oliveros’s Meditative Works.” MA Thesis, University of Arizona, 2020.

Renihan, Colleen. The Operatic Archive: American Opera as History. New York: Routledge, 2020.

Revell, Irene. “Live Materials: Womens Work, Pauline Oliveros & the feminist performance score.” PhD Diss, University of the Arts London, 2022.

Sanmartín, Paula. “‘Custodians of History’: (Re)Construction of Black Women as Historical and Literary Subjects in Afro-American and Afro-Cuban Women’s Writing.” PhD diss., University of Texas, Austin, 2005.

Sheppard, W. Anthony. Revealing Masks: Exotic Influences and Ritualized Performance in Modernist Music Theater. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001.

Silva, Daniel F. “(Anti-)colonial Assemblages: The History and Reformulations of Njinga Mbande.” In The Routledge Companion to Black Women's Cultural Histories, edited by Janell Hobson. London: Taylor & Francis, 2021, 75–85.

White, Hayden. The Practical Past. Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press, 2014.

Zimmermann, Walter. Desert Plants: Conversations with 23 American Musicians. Vancouver: Aesthetic Research Centre of Canada, 1976.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.