Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit (2012) belongs to that corpus of cultural productions that are all-black cast but are produced and finance by white, mainstream finance and this relationship brings multi-layered complexities. This black-art-white-finance arrangement does not auger well with the ideological positions of the black-white politics in South Africa, in that it introduces into the production ambiguous, irreconcilable clashes that pit Africans’ call for liberation on the one hand, with the maintenance of the logic of coloniality on the other. Ziyankomo selection of its historical narrative adds to this ambiguity in that it eschews honest reflections about Africans, in this case, the Zulu historical experience and the violence of the colonial encounter. Instead, it opts for selective experiences that recreate detached, ahistorical surface representations, which fly in the face of the calls for decolonisation (Ngugi 1986) and decoloniality (Mignolo 2018). Arguably, Ziyankomo’s take on the motif of the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior locates it with a collection of South African productions whose revisiting of the image of the dancing Zulu warrior marks continuities with racist, colonial British representations of the Zulu warrior of the Empire Exhibitions and falls into anthropological politics of the 1930s whereby there were massive calls for the retribilisation of the Bantu, the indigenous people of South Africa. Drawing from interdisciplinarity of epistemologies of Walter Mignolo’s concept of decoloniality this article, intends to explore the historical underpinnings of ideological ramifications of the anthropological turn, which betrays long shadows of colonialist-apartheid values and their constrictions of post-apartheid contemporary African opera performances. The article argues that Ziyankomo is firmly located in cultural productions meant for exotic entertainment while simultaneously obfuscating contingent historical realities affecting Africans. The question the article raises relates to value systems within a whiteness culture of erasure. Who funds black opera and how can such funding structures be seen to be advancing a decolonial question? Ziyankomo then in this discussion becomes anchor and site to investigate black opera production and issues of social justice within the current structures of its funding model.

Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit was performed on 10, 13, 15, and 17 March 2012 at the State Theatre and 23, 25, 29 and 31 March 2012 at the Joburg Theatre. The production was the second instalment by Opera Africa in its commitment to producing new work in isiZulu language, the first having been the internationally acclaimed Princess Magogo KaDinizulu (2002). Aside from these productions, Opera Africa produced several classical canons which it re-imagined for the South African context. Ziyankomo was crafted under the production eye of Sandra de Villiers, the co-founder of Opera Africa, with music by Phelelani Mnomiya (1960–2020), an established choral and gospel composer, and the libretto by Themba Msimang (1944), a talented isiZulu-language literary giant. This article examines Ziyankomo to assess if it can participate in decoloniality practices. Central to these considerations is how a supposedly Black opera participates in an industry shaping vexing, contingent politics of racial capitalism that continue to flout transformation in post-apartheid South Africa. I explore the extent to which the history of performing race in theatre, opera funding in South Africa, visual representations and African-language literary politics, all together contribute to reading Ziyankomo’s complex and contradictory role in the reclamation of Zulu cultural history. Through Ziyankomo, and against the backdrop of Black opera studies in South Africa, on the continent and globally, I question the extent to which opera can participate in decoloniality discourse.

My critical inquiry draws from Walter Mignolo’s writings on decoloniality as developed from Aníbal Quijano’s concept of coloniality.1 Both frameworks will be used to examine a representation of the dancing Zulu warrior in the history of theatre and its ties to South Africa’s racialised cultural and political economies. Both Quijano and Mignolo’s concepts are foundational in rethinking Black opera’s position, its articulation of the African/Black experience as consequences of repertoires of violence, visited upon them by colonialism and slavery. Quijano’s concept of coloniality has opened up spaces for the reconstruction and restitution of silenced histories, repressed subjectivities, subalternised knowledges and languages performed under names of modernity and rationality.2 In this discussion Quijano’s concept will be tied to Mignolo’s concept of decoloniality to problematise how universalised art forms such as opera engage claims to being vehicles through which the materiality of the human condition may be addressed. Stanton observes that “contemporary hegemonic forms of Eurocentric subjectivity have no imperative toward decolonization.”3 This is because historically, European colonialism and modern coloniality sedimented epistemic biases that produced normative ways of being, and consciousness that have been internalised and regenerated throughout the worlds that experienced colonial contact.

Using the frame described above, I explore the overlap in meanings of the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior by tracing it to its historical emergence in British colonialism. I analyse how this historical antecedent created spaces for staging Blackness for South African post-1994 audiences socialised into contested perceptions of white superiority and the inferiority of the other. Using the coloniality-decoloniality lens the aim is to scrutinise, how these perceptions have (im)perceptibly evolved in South African racial history and affected white people in their common view of Africans as the racialised other. In this manner, I argue that Ziyankomo cannot be accounted for in the absence of the rhetoric of race (Black versus white) and the foundational political economy that is important to its material racial difference, which however, indigenisation of opera rhetoric attempts to conceal. I further argue that even though the production locates itself in the precolonial Zulu world, its structural absenting of colonial whiteness from the period the opera is set in ironically draws attention to its eschewing realities by concealing past foundations of marginalisation it ought to be revealing. In other words, Ziyankomo’s presentation of a mendacious colonial Zulu cosmology, free from the violence of colonialism, using a Western-derived, exorbitantly expensive art, ironically, obscures and draws attention away from the very foundations of the colonial-capitalist logic necessary for the opera’s production, thus allowing for continued forms of framing knowledge in ways that favour European norms of intellectual production.

It is difficult to position opera in its classical definition, social function, recycling of its traditional repertoire, and the political economy of its production as a genre associated with discourses of decoloniality. It is a challenge for the opera industry globally to respond satisfactorily to transformation drives calling for the decolonisation of the operatic repertoire, equity in casting and indigenisation of narratives. Likewise, key institutional performance frameworks such as artistic quality and innovation, audience development and access, institutional governance and leadership, cultural and social impact as well as commercial profitability unobtrusively gravitate away from established conventions. The South African opera industry, in which Black opera participates, aligns itself with these particularly Western operatic institutions from which it is derived through colonialism. Though this is the case, the genre in South Africa is indigenising in attempts to break away from limitations of classical conventions to form a distinctively South African opera.4 The effects of these attempts are yet to offer a clean break. It is in view of these observations that South African opera in its traditional form still belongs to a larger field of European art forming a European modernity that is “hopelessly entangled with economic, political and epistemic sources of power established through European colonial violence.”5 This entanglement makes South African (Black) opera occupy an ambiguous position which is inexorably imbricated in complexities that undergird some of the darker tones of colonial modernity. By zooming into Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit, this article investigates Black opera in South Africa questioning whether it can be a vehicle for decoloniality discourse.

Arguably, Ziyankomo continues the staging of the colonial logic of racial supremacy and belongs to a long performance history that conflates the entire complex gamut, of non-symbiotic relations between Black art and white patronage in South Africa. A case in point is the flattening out of the historical Zulu identity and socio-political experience in the Western popular imagination. Fascination with the image of the Zulu nation has historical antecedence; from the British Empire Exhibitions of the 1850s, which laid foundation for the racist othering of British subjects. Charles Caldecott’s 1853 exhibition staged Zulu tribal lives and later, lives of other natives from all over the British Empire.6 According to Rob Power these exhibitions produced, circulated, sold racism to the British and made it a norm for the British subjects throughout the Empire. Entertainers, showbiz managers, writers and prospectors drew from pseudo-scientific theories to present racial difference to project an identity of white British’ “greatness” as owing to “the dynamics of racism in Britain which carefully stage-managed interaction between Black people and white people, all with an intention to assert white cultural dominance.”7 This ideology also permeated South Africa racial-cultural politics. It found elaboration from the turn of the twentieth century with the dramatic performances of the Bantu Men’s social club. From the 1930s, the Bantu Men’s Social Centre, an elite African cultural fitment, founded and wholly funded by the South African Institute of Race Relations premiered several musical plays and theatre productions some of which celebrated the British bourgeoisie sensibilities, and another which celebrated African Americans’ emancipation from enslavement.8 Among the musical plays premiered in the decade of the 1930s is Moshoeshoe, written by HIE Dhlomo, a musical play in a series of other plays about past indigenous kings. Moshoeshoe was hailed by white cultural brokers and rejected by urban Black audiences, including those who were in the Free State, the historical area of Moshoeshoe seat of power. African audiences perceived the play as preoccupied with African tribal antiquities, an aspect white liberal South Africa mainstreamed in their attempts to retribalize modernising South Africans.9

Again, in 1959, King Kong, a jazz musical by Todd Matshikiza, a Sophiatown intellectual, was premiered at the University of the Witwatersrand Great Hall. The production drew on African urban music genres that have accrued up to the exhilarating decade of the 1950s. In this case too, the Union of South African Artists loaned from a rich patron, the African Medical Scholarship Trust Fund, affluent individuals such as Robert Loder (who worked for the Anglo-American Corporation), Edward Joseph (a stockbroker), John Rudd (a business executive), Ruth Hellman and from group and personal connections as well as purchasing of advertisement space in the King Kong programme, for the production. Interestingly, the musical played to mixed-audiences, two thirds of whom were white and liberal. In that way the musical was framed as a stance against the apartheid government’s racist laws that prevented a mixing of races.10

Another musical, Ipi Tombi/Ipi N’tombi (1974), a Black-themed-white-financed production by Betha Egnos Godfrey and her daughter, Gail Lakier, posited itself as a celebration of Black South African culture.11 It was well received in South Africa and in major metropolitan cities globally, but it was at the Harkness Theatre on Broadway where the musical attracted negative criticism, with protestors saying the play presented false impression of life in South Africa. Other musicals of the same constitution are Welcome Msomi’s UMabatha (1971) and Joan Brickhill and Louis Burke’s Meropa (1974), renamed Kwa-Zulu for its England tour.12 Ipi Intombi was revived in 1997, and played at Baxter Theatre, University of Cape Town.13 It added themes of a clash of cultures, generational clashes, the land question and reclamation of one’s heritage. In UMabatha and Meropa, and both versions of Ipi Ntombi, the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior featured prominently. It is in view of these observations that a detached symbolism of the dancing heroic Zulu warrior comes across as misplaced in the South African performance history attesting to the views that the underlying significations in Ziyankomo opera connect it to this performance tradition, which subtly reinforce Black-white relations, albeit, under the hegemonic sway of whiteness in the 21st century.

With regard opera in South Africa, Ziyankomo belongs to a history of indigenising opera practices that started in 1801 and became nuanced post-1994.14 Earlier work such as Michael Williams and Roelof Temmingh’s Enoch, the Prophet (1994), Sacred Bones (1996), Buchuland (1998); Mzilikazi Khumalo’s Princess Magogo kaDinizulu (2002); Michael Williams and Mats Larsson Gothe’s The Poet and the Prophetess (2008) and a significant number of other operas, introduced aesthetic norms that exchanged musical practices from Western-derived operas in experimental ways. This evolution increasing led to innovation by other Black composers who reflected on local subjects and drew on African indigenous music heritage, not only as colouration of their compositions but also for disrupting intrinsic operatic musical idiom. Even as the notion of indigenisation is important for debates on how a Western form, such as opera, roots itself in colonial countries such as South Africa and elsewhere, it significantly adds but differs from the concept of decoloniality. Decoloniality takes things further as it critiques the lingering effects and dominance of the Western forms of economic power, intellectual production and being, which privileges European ways and marginalises others. Decoloniality calls for an active push back against Western forms of power structures through delinking, epistemic disobedience and the reclamation of local knowledge, cosmologies and cultures, for the construction of a world where all local histories and civilisations are equally valid.

Black opera’s positionality as an indigenising music innovation is not questioned herein, but what is problematised in this discussion is the thought of Black opera as participating in decoloniality practices within the structures established by Western-influenced operatic institutions undergirded by the lingering, dominant architecture and structures of Western cultural and political economies. Ziyankomo becomes central to this debate owing to its political economy and production framework. In terms of its treatment of its subject matter, Ziyankomo further posits itself as a site where coloniality-decoloniality clashes exist in the same text owing wholly from the material history that it both reveals and conceals. Its content falls short from colonial-derived racial relations, and historiography that obfuscate, dilute and layer guises of (dis)continuities of rationalities that prop enduring forms of colonial whiteness in South Africa. The following sections expand on these contentions.

In Europe and America opera companies dependent on private donors or government funding which manifest their interests through a notion called “risk avoidance” programming or what the contemporary opera composer, William Schuman, codified as “timidity programming”.15 According to this programming practice, conventional programming is preferred over high-risk 20th century work for a variety of reasons which in the main has to do with tastes and preferences of opera communities, local politics, funding by both national government and local municipality. This programming affects Black operas negatively most of which fall within what would be called high-risk operas because they are newer compositions and are unfamiliar to audiences used to canonical works.16 Markus Tepe and Pieter Vanhuysse, Lena van der Hoven, Sakhiseni Yende and Vusabantu Ngema and others provide case studies of how opera is aligned with the state or elite classes for pursuance of national and political agendas.17 For example, Opera Africa financial reports for the period 2012–2018 show that it had 10% for the company’s operational costs. To mount a production, it needed substantive fund to cover for the cast of 55 singers, 36-piece orchestra, support team, transport and accommodation. In an application it put through to one of their main funders, it received 0.55%, which was for formatting of scores and orchestral parts in line with the standards set by the funder. In another instance, Opera Africa approached another state funder for helping it realise the touring of its fully indigenised African opera. After a delay of two years, it received a response from the funder that indicated that out of the original amount requested it could only be allocated 20% leaving the company to raise 80% of the deficit from private donors and patrons, some of whom have relations to past governments interests or the neoliberal post-apartheid business class or international conglomerates.18 According to the company’s little books for their different productions, Opera Africa funders are Department of Arts and Culture, National Arts Council, MTN, Distell, ATKV, RSG 100-104fm Dis Die Een, Maponya Mall, Lufthansa A Star Alliance Member, Standard Bank, Arts and Culture Trust, National Lottery Fund (a core funder), South African Music Rights Organisation (SAMRO), Rand Merchant Bank, South African Theatre and The Mandela at Joburg Theatre. For Ziyankomo’s production, the latter eight companies provided various amounts to make up for the shortfall which could not be provided by their core-funder.

Mary Ingraham, Joseph So and Roy Moodley make similar findings for the intransigency of opera. They observe that, the historical tangible and non-tangible monuments of colonialism continue to cast long shadows of colonialist values and constructions on contemporary performances, not only in the mounting of historical works, but also in the creative production of new works.19 There is hope though Joshua Tolulope David work on the production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute for the Nigerian audiences shows how this reimagination set the tone to think about decoloniality when indigenizing opera.20 While Ziyankomo attempts the same, there are representations that are antithetical to the Zulu society which makes it ring hollow of its intensions.

Questions that arise specific to the operatic tradition in general, and Ziyankomo specifically relate to: Ziyankomo’s content, can it be perceived as a decolonizing and decoloniality discourse? Can South Africa’s opera industry’s agenda of incorporating Black opera into its financial ecologies which has long tentacles stretching back to colonial-apartheid enterprises be ignored even as they frustrate South Africa’s broadly encompassing transformative agenda? Is the production process, political economy and content of Ziyankomo aware or oblivious of proverbial whiteness tendencies to control and manage the transformation agenda in attempts to maintain the status quo? Can Black opera be truly Black if the means of production are still firmly locked in the hands of the (white) capitalist class, whose intentions in South Africa are associated with extraction of Black labour, including the labour of professional opera singers? And what is to be made of small opera houses who have relations with white capital class as donors and providers of infrastructure, but also disrupt dominant culture by questioning debilitating legacies of colonial-apartheid violence on Black subjectivities?

Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit is a one act opera based on a historical tragedy; a forbidden love relationship between King Mpande’ concubines and the sons of his most trusted and influential Prime Minister, Masiphula.21 The setting of the opera is circa 1850s at the Palace of King Mpande KaSenzangakhona, half-brother of King Shaka, the only survivor of King Dingane’s bloody reign. The curtain rises on three women gossips (sung by Caroline Modiba, Andiswa Makana and Amanda Rakale) confirming that the King’s maidens of isigodlo are for the King alone, they are the King’s “flowers.” The stage setting is simple; a shark screen forms the background with an illuminated shield-like figure on which is an image of a mask of a Nigerian deity. The illuminated shield-like formation is also used to project translations of lyrics. On a four-stepped stage platform, a choir ensemble costumed with drawings representing a host of Nigerian gods repeats the injunction. The entire costuming of the ensemble; flowing Black gowns, with gloved hands in red and white colours are far-fetched for the Zulu ethnic regalia and the historical setting for the opera. These cult significations are pointing more to pantheons of Nigerian religious gods, mythology and tradition, rather than the Zulu belief systems and cosmology. The gossips caution the guards of the King’s maidens to make sure that none are tempted to stray by any of the virile, good-looking warriors. Two couples, Ziyankomo (sung by Given Nkosi) and his love, Gabisile (sung by Kelebogile Boikanyo); and a second warrior, Makhosini (sung by Aubrey Lodewyk) and his sweetheart, Nomakhwezi (sung by Thembisile Twala), are seen sneaking around.

In the opera, the bliss of these lovers is shattered by guards, (sung by Phenye Modiane, Simon Mashike and Thomas Mohlame) when they catch them, right on the premises of the King’s royal enclosure, and bring them before the King, (sung by Fikile Mvinjelwa). The setting changes and the spotlight falls on the King and his royal council consisting of his Prime Minister Masiphula, (sung by Thando Zwane), uMntwana (Prince) uCetshwayo, (sung by Esewu Nobela), women of the court, and the warriors. The setting has ten Black and white shields, (four on each side of the two big shields on the left and right side of the stage) forming the background of King Mpande’s court. The colours of the shields bear the most loyal adherence to the historical period. Oral accounts state that regiments who were age mates of King Mpande, such as uMxhapho also known as iziMpunga, uDlambedlu and iQhwa, were known to have carried black and white shields. Even with this single accurate depiction of the era, misappropriations in the details about the period and Zulu traditional heritage point to concerning tendencies by dominant cultures, especially white cultures in South Africa, that amalgamate indigenous people’s cultural values and norms in unsettling ways while at the same time reinventing these traditions. In the case of this opera West African spiritual belief symbolism and the misappropriation of Zulu national couture and practices are meshed up into one dramatic spectacle and represented as the post-apartheid Zulu episteme and cosmology. The production team’s sartorial choices used synthetic, inauthentic garments; contemporary customised look-alike cloths procured from outside-culture manufacturers exploiting Zulu cultural symbols through misappropriation and who reduce South African indigenous community to mere consumers of commodities supposedly representative of their culture. Further, even as a pan-Africanist signalling is manifest in the overture and costuming, inattention to ethnic-bound detail and the exclusion of local cultural custodians in the procurement of proper sartorial elements continues colonial tendencies of flattening African identities and superimposing European-based views of these identities and knowledge produced about them. The opera in this way functions within coloniality of power, “which produce distorted paradigms of knowledge and spoil the liberating promises of modernity.”22 Ziyankomo struggles to delink from the European continental philosophy and phenomenology transplanted to the colonial frontiers during settler invasion. It operates within the European colonial matrix of power which devalues and erases “local histories that do not correspond to the local history of the heart of Europe.”23 The Pan-Africanism intended in Ziyankomo through these symbols lead to entangled coexistences in power differentials.24

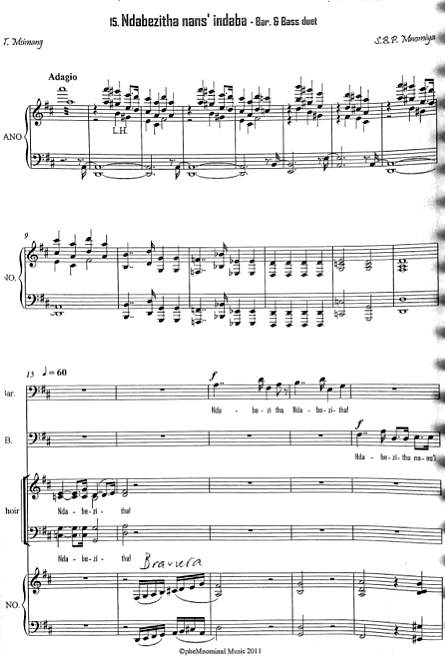

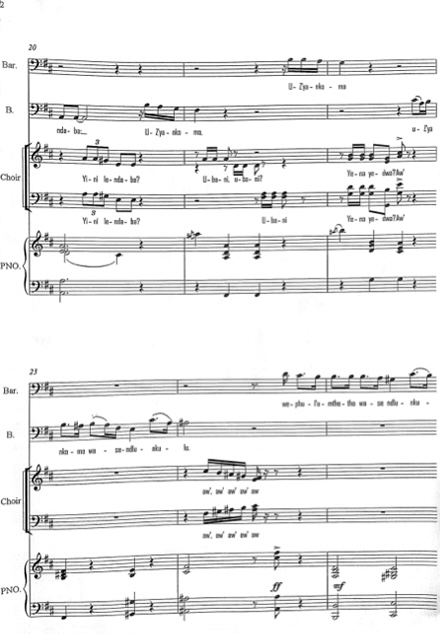

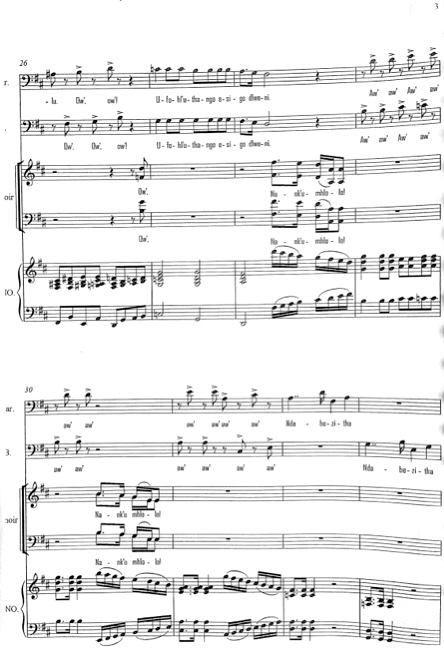

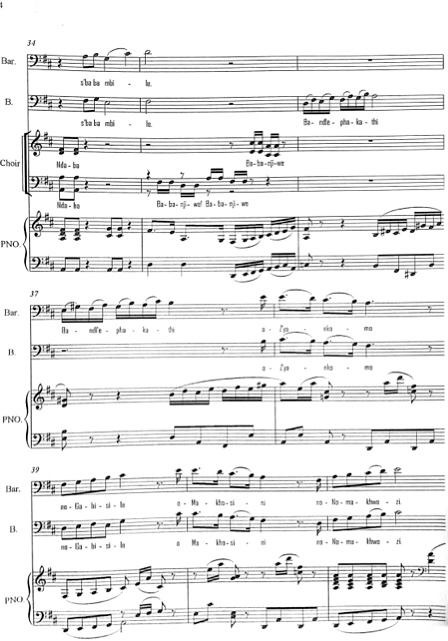

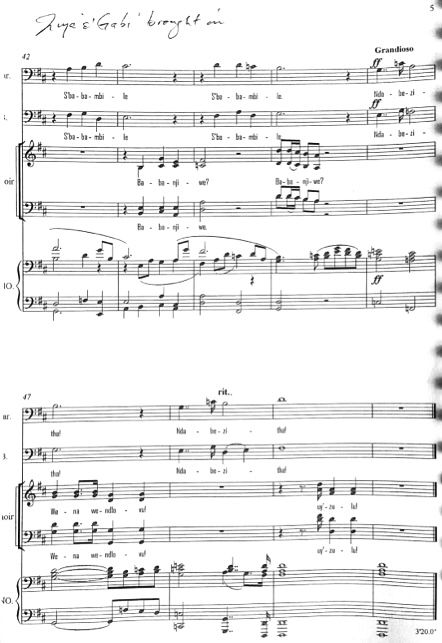

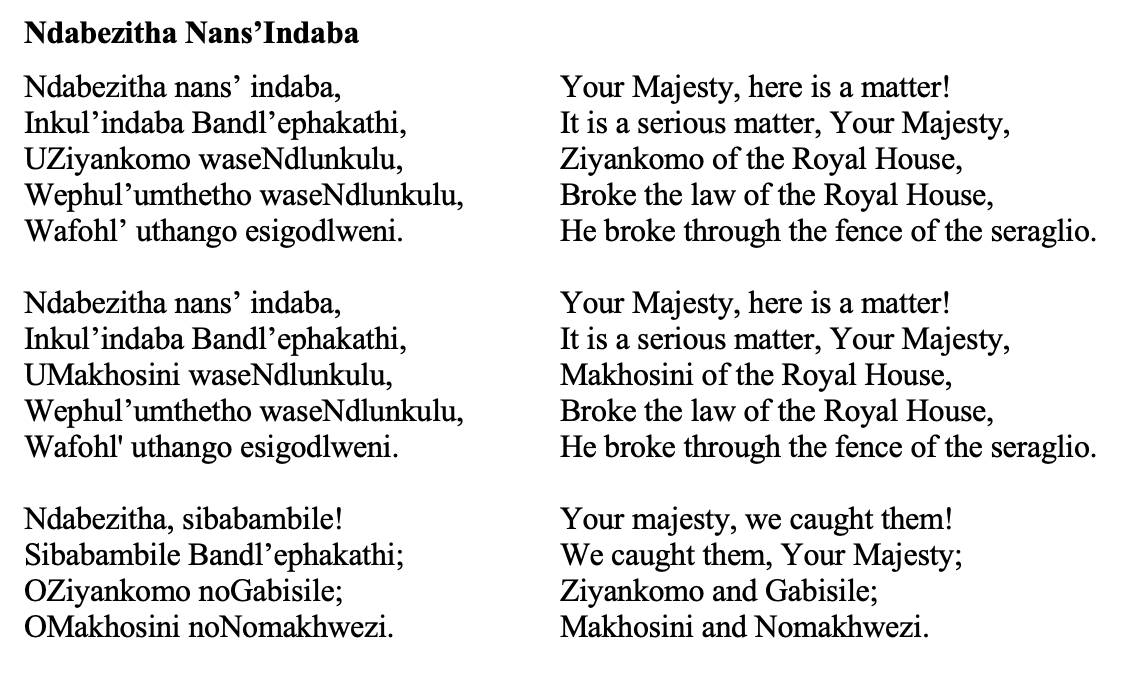

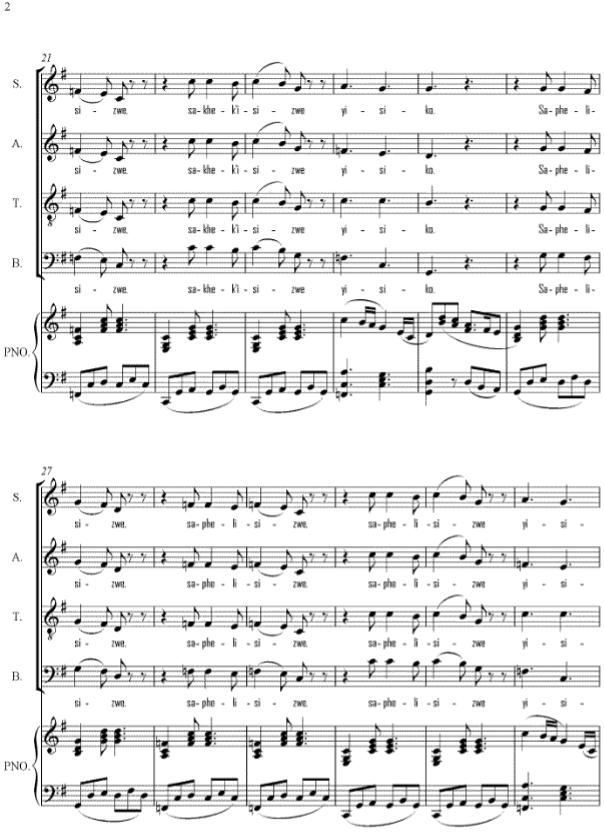

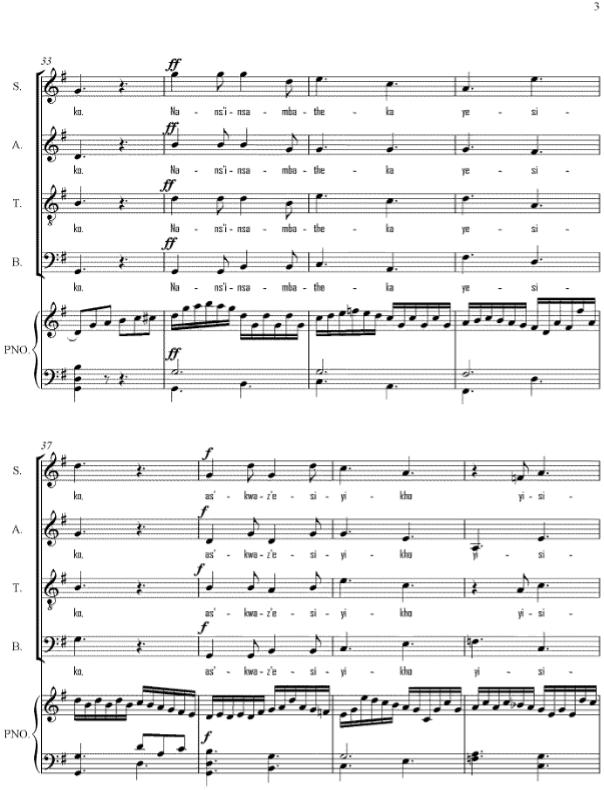

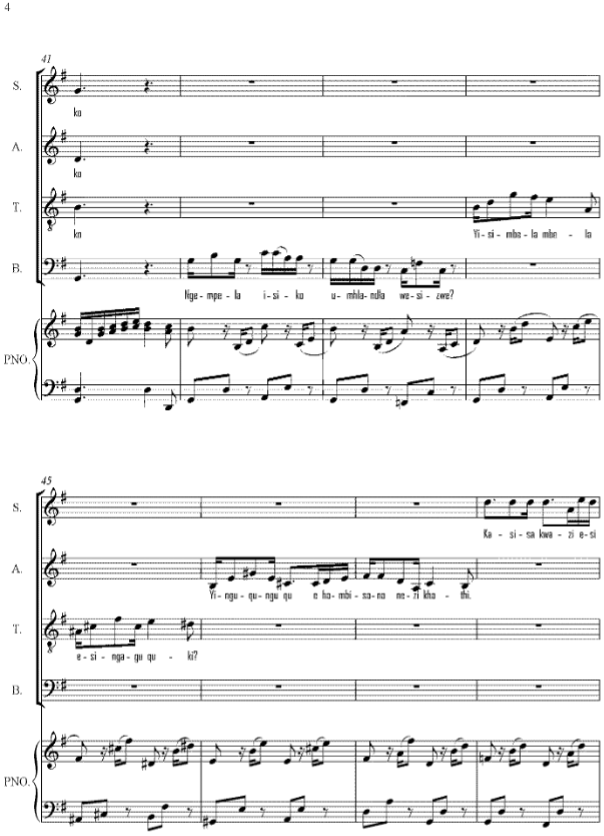

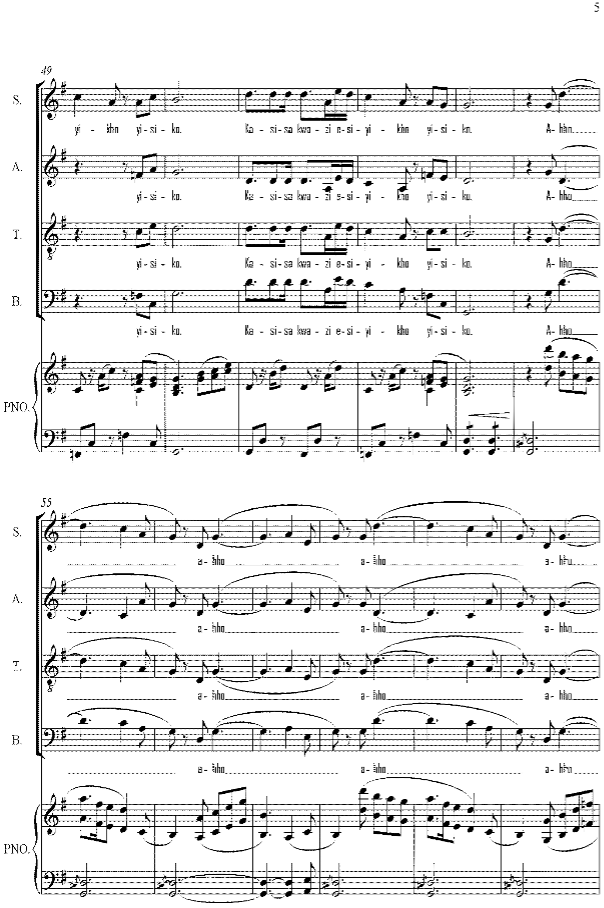

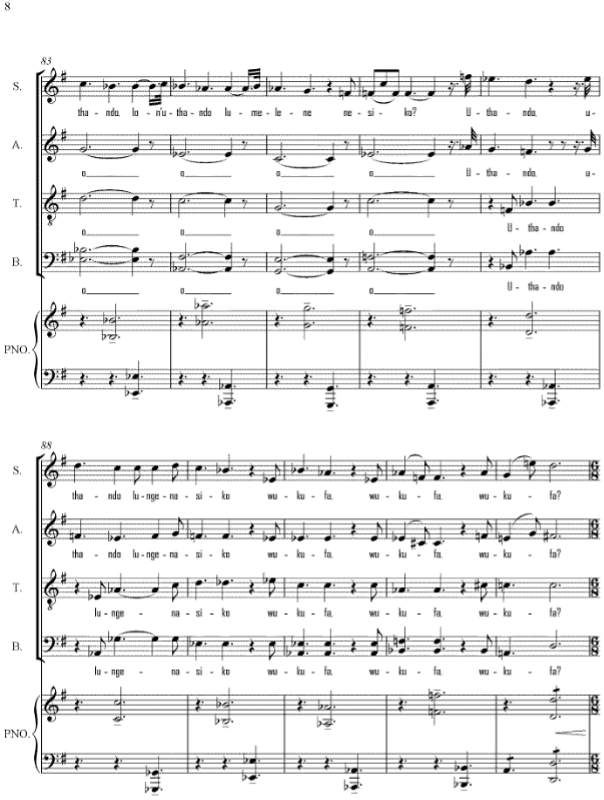

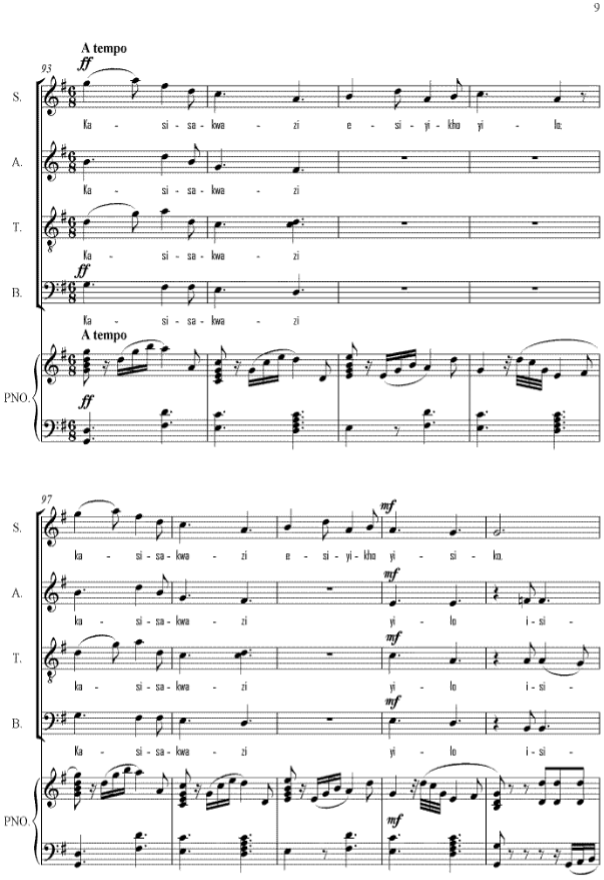

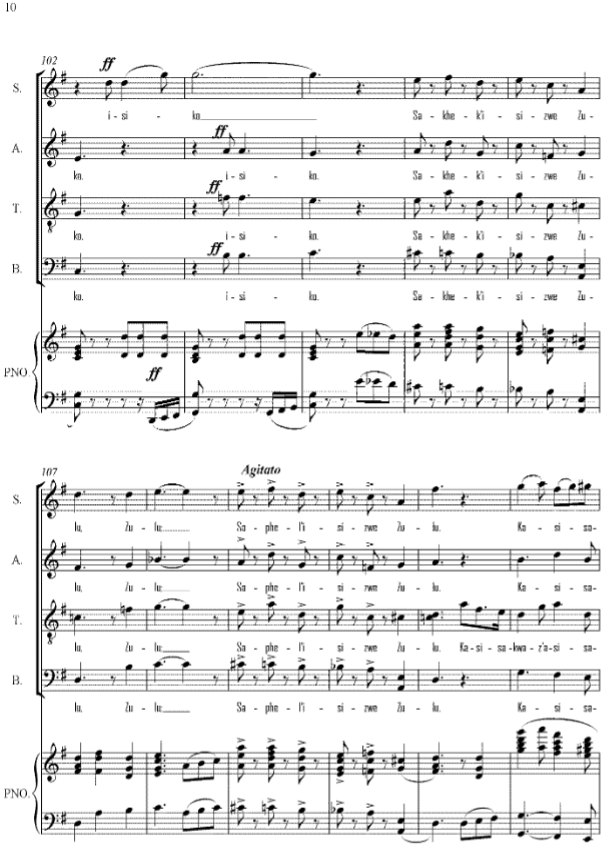

Aside from these vexing inaccuracies in ethnic detail, the music sang during this moment, of charging Ziyankomo is exhilarating. For its aural comprehension, I depended on the renditions; Ndabezitha Nansi’Indaba and Ntab’Ezinhle, local school and adult choirs sang for the Meloding yaTshwane Music Festival in 2023. The choirs and the orchestra at this festival were accompanied by a fully orchestrated score, unlike in 2012 at the time of the opera’s premiere when the entire opera was performed with only the piano as accompaniment. In the opera, the song both the SABT and TB voices presented for charging Ziyankomo is Ndabezitha Nans’ Indaba:

The song triumphantly announces that the disobedient young people have been arrested committing an abomination in the palace. Underlying this disobedience is an intergenerational conflict between those siding with tradition and the young lovers’ defiance of traditional custom because of their convictions about love. The gleeful emotion of the traditionalists is conspiratorially introduced through the SABT voices and TB voices, firstly, by singing a royal salutation, Ndabezitha! a once contentious salutation that a colonial secretary of native affairs, Theophilus Shepstone, wanted to outlaw for King Cetshwayo, and reserve it instead for white colonial officials. The Zulus resisted, hence it continued to be used as a sign of profound reverence up to present times, not only for the Zulu monarchs, but also for all indigenous royal houses of South Africa and eSwatini. This salutation is followed by an exhortative “Nans' indaba!” establishing not only the urgency of the matter, but also an expression of clandestine expectations for quick and immediate actions to be taken against the wretched lovers. In terms of the presentation of this charge Mnomiya uses clear functional harmony and SABT voicing. The call and response assume antiphonal textures, at times started by the two male voices and at others, alternating with the choir using parallel motions to anchor vocal writing imitating African natural speech, for an example the exclamations establishing surprise, “Awu!” “ubani?” “nank’umhlolo!” and so forth. These aural interjections are language prosodic features with which Mnomiya grounds his harmony, melody rhythm and meter, form and structure, text setting and vocal texture, as well as the African idiomatic influences to strong African traditional and contemporary spoken language and singing traditions.

In interpreting the juxtapositioning of the royal salute and the youngsters’ defiance, it is clear that the young couples’ wilful challenge of the custom is a hidden text in the opera meant to undercut the power and authority invested in the monarch and the reverence the royal salute extract as a social contract. Whereas Scott’s use of the concept was by subalterns challenging the authority of the state,25 in this opera, the subalterns have been subsumed as they are made to mask colonial-apartheid interests, which throughout history have been geared to undermine the entirety of African traditions. For the colonial-apartheid project, the historical King Mpande was favourably perceived because he succumbed to the Boer and colonial officials after the annexation of Natal; he was foundational to the white people’s building of lasting legacies in South Africa.26 However, from the traditionalist Zulu nationalists’ point of view, King Mpande was the least revered for his indolence in his leadership of the Usutu Royal House. His failures caused allegiance for the royal house to be transferred to his warrior son, uMntwana uCetshwayo. In the opera the politics that characterised the historical generational conflict between King Mpande and uMntwana uCetshwayo are abjured, instead they are projected to tensions playing out between Ziyankomo and Makhosini as the younger generation, and King Mpande and Prime Minister Masiphula as the older generation. Even then, the opera does not provide contexts to make a case for the reasons why the young men - taught in the ways and traditions of the land - intentionally transgress this law knowing that it is punishable by death, or for the women of isigodlo whose power is owing to their proximity to the King also disobey injunctions of being umdlunkulu (women of the royal house). Instead, the opera is preoccupied with showcasing Ziyankomo’s prowess, as a greatest warrior-dancer before he is executed.

In the history of African letters, the Dhlomo brothers, HIE Dhlomo in Cetshwayo and RRR Dhlomo in UCetshwayo allude to this growing disregard for custom around the same period this opera is set. HIE Dhlomo shows that the basis of this disrespect for tradition is at the feet of colonial officials,27 and the disintegration of the Zulu society because of the growing influence of British colonial modernity. The opera’s avoidance of representation, involving King Mpande who fled King Dingane from Kwa-Zulu to colonial-administrated Natal, makes it hard to ignore the ahistorical nature of the generational conflict occasioned by British colonial disruptions of Zulu society.28 Ziyankomo’s execution goes against any historical record, especially, in view of how the colonial officials, missionaries and white settlers viewed these arbitrary executions of ordinary people by their kings. What the opera erases are myriads of conflicts, internal and external to the Zulu kingdom, during which King Mpande’s lethargic rulership caused a Zulu civil war – his sons, Mbuyazi and Cetshwayo fought for leadership.29 Further, what are erased are King Mpande’s successes too, as “the most enduring kings of the Zulus. He avoided the incessant attempts by the Voortrekkers and the British to meddle in Zululand internal affairs.”30 Even with that being said, King Mpande’s land policies were a problem: he gave white people large tracts of land as a compensation for their support in gaining the kingdom. As though this was not enough, white settlers unlawfully occupied land under his watch.31

Although Canonici and Cele are of the view that historical fictions are just stories set in the past, however, “history provides actual facts, while fiction provides universal interpretation that makes the facts relevant and meaningful for those who are able to read between the lines at the particular time”.32 Therefore, the opera’s historical canvass is significant for the claims it makes to epistemic generation, especially in its attempt to be seen as charting a different path from conventional opera. Even though the opera downplays the historical significance of King Mpande in Zulu history, the opera exists in intertextual relations with several isiZulu fictitious treatments of the Zulu past with storylines and characters drawn from known events. In addition to HIE Dhlomo’s Cetshwayo, RRR Dhlomo’s UCetshwayo, Vilakazi’s Khalani MaZulu (in Inkondlo kaZulu) and NgoMbuyazi eNdondakusuka (in Amal’Ezulu), Ndelu’s Mageba Lazihlonza, Hlela and Nkosi’s Imithi Ephundliwe, Blose’s Uqomisa Mina Nje Uqomisa Iliba and Msimang’s Izulu Eladuma Esandlwana share commonalities in that their references derive from known history.33 Irrespective of their ideological leanings, they reflect or foreground the encounter between the British colonialists, the Boer Republic of Natalia, Christian missionaries, white settlers, and the Zulu Monarchs and their people as a basis of narration. The erasure of this important history in the opera, constricts and confines it within the coloniality project, where local histories are erased, especially, the histories about violence visited on Black people by white speculators, or internecine wars, or Black-on-Black violence instigated by white settlers and colonial officials and Boer farmers, or/and land grabs by the colonial-apartheid administrations and the Africans’ struggle against land dispossession. In the history of Zulu and African Nationalism the land question has remained a central challenge in radically transforming South African political and social landscape.34 Thus, the omission of the land question cuts out large chunks of histories of arbitrary dispossession of Africans of their lands by the white race.

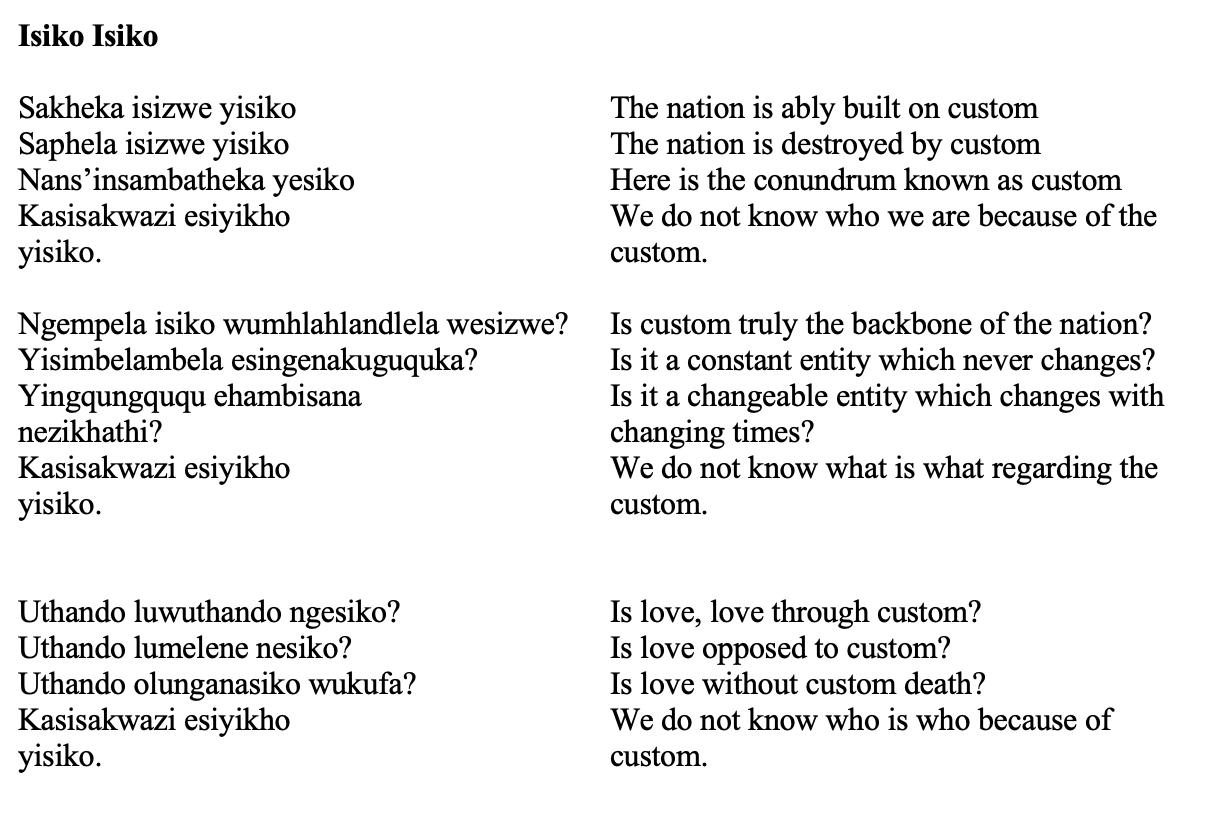

Ziyankomo’s omission of central historical detail of any contact between indigenous people and the British in South Africa opt for a technique well-established in South African visual media; that is, structured absence.35 However, in this case there is reversal of the race structurally absented; in this instance, whiteness is structurally absented with an intention of erasing the repertoires and grammars of genocidal violence of whites’ historical imprints in contemporary African popular imagination. The opera creates impressions of a pre-colonial past, which imagines a period when autonomous Zulu power and prestige still held sway. The central irony of course is that the recreation of characters bearing the names of historical figures such as King Mpande, Prime Minister Masiphula, and uMntwana uCetshwayo necessarily places the opera within a historical timeline during which European interests by different white ethnicities coalesce and organised themselves around the dispossession of the Zulu society and by extension Africans, of their land, the dismantling of Zulu society’s social and political organisation; and the undermining of their culture and humanity. In this way, the structured absence of the white race works within the greater predetermined frames of whiteness generally which are brought home by the closing song, Isiko, in the opera:

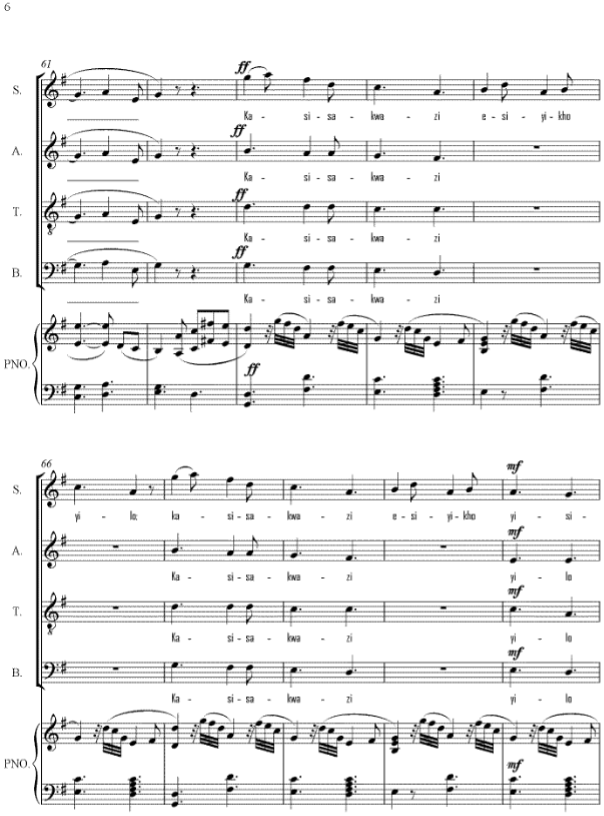

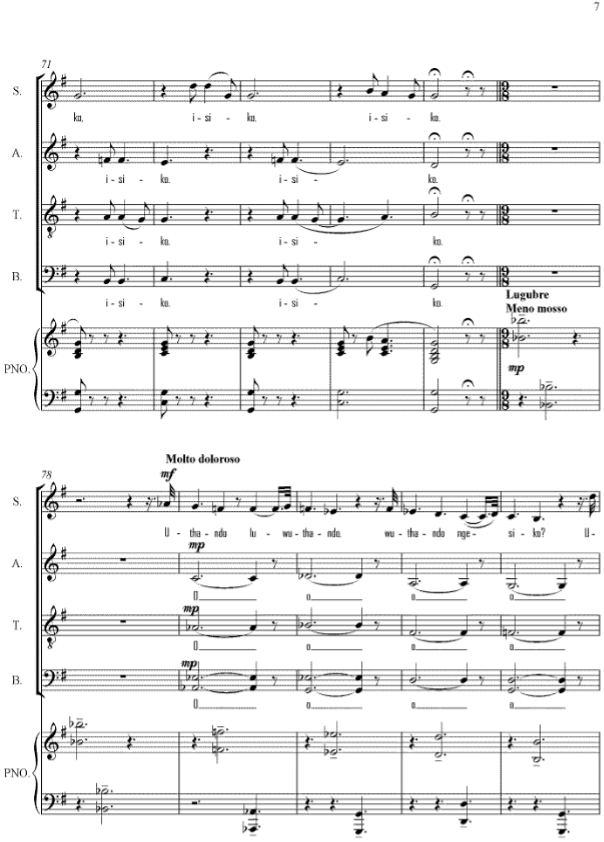

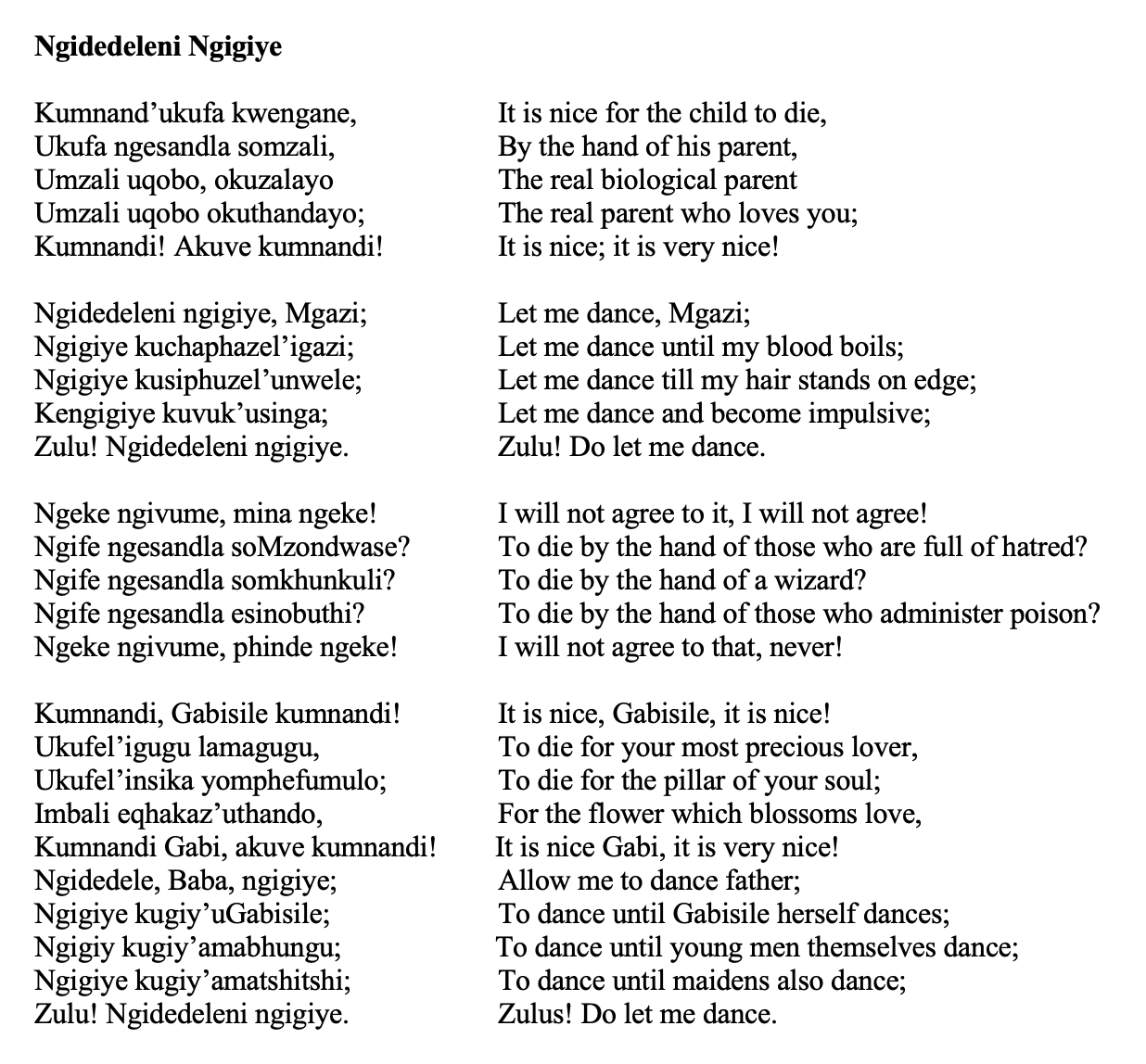

The questioning of tradition and culture in this song implies modernism influences characterised by the rejection of tradition, alienation and disillusionment, individualism and subjectivity, and belief in progress and innovation. The opera presents tradition, culture and custom as an enigma opposed to individualism, subjectivity and change. The first three lines of the first stanza allude to tradition as a maker and destroyer, but largely, the destroyer of life and society. The subsequent rhetoric questions juxtapose tradition and change, and how the rigidity encapsulated in tradition is inimical to individual’s freedoms. At individual level, the alienation and disillusionment of the lovers highlight the effects of traditionalism on the psychology of all characters; Makhosini deserts his lover, Nomakhwezi feels betrayed, Gabisile commits suicide and Ziyankomo becomes sardonic and his entire worldview is distorted. His dancing song, Ngidedeleni Ngigiye, establishes his disenchantment and signals that he is on the verge of a psychiatric delusion in his denunciation of tradition:

In a state of utter melancholy and self-abandonment, he charges in defiance that he must be let to dance because he is going to be enjoying being killed by the hand of his father. He accuses the world for which his father stands of hatred, witchcraft, and toxicity. He declares that he chooses death rather than exist in a society that put boundaries on the most primal feeling of human affection. Directly addressing his father, he obstinately implores him to let him be and rally the younger generation to join him in a dance of death; who joins him by clapping hands from bar 79-84, while also interjecting with encouragement quoting his honorific name, Mgazi, right there in the presence of his father, his senior and the rightful bearer of the clan name at this moment.

In terms of the argument of this discussion; the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior and encouragement to move away from traditional prescriptions cannot be overlooked. This message, within the broader historical context of colonial contact, has been a persistent discourse.36 The opera displays that tradition has no place for young people, even if they were to be distinguished. By offending tradition Ziyankomo is not spared and his loss is not lamented by traditionalism. His loss for this society is expressed by Cetshwayo, a peer, in a song Ntab’ Ezinhle. From historical supremacist frames of reference, the demise of Ziyankomo cannot be underemphasised; the opera carries a subterfuge mockery of the Zulu kingdom that has since succumbed to colonial-apartheid domination. According to Benedict Carton and Robert Morrell the perceived violence embedded in Zulu warriorhood formed the basis of its denunciation by the colonial government of Natal. Well-drilled and highly motivated Zulu regiments were a force that represented formidable danger to colonial Natal and settler community, thus the demonisation and machinations to contain it resulting in the commodification of the warrior image from the period of the migrant labour system up to contemporary times when it has become part of harmless tourists’ attraction.37

Furthermore, the performances of the dancing warrior have been appropriated into modern performance events, mainly funded by the neo-liberal corporate sector either as “heritainment” or for displaying celebrations of the taming of a once heroic ethnic nationalism.38 Within the tradition of Black cultural production in South Africa, the Black-art-white-money industrial complex is fraught with the funding of folklorish performances in non-innocent ways, where obfuscation of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic ideologies coalesces in unsettling ways. It is in view of the foregoing views that the framing of Ziyankomo becomes a hard sell in including it outright in decoloniality practices.

According to critical race theories, whiteness is a social construct and a social location of power, privilege and prestige. As a metaprivilege, “whiteness has an ability to define the conceptual terrain on which to set the tone of how race is constructed, deployed, and interrogated. Whiteness generates a distinct cultural narrative, controls the racial distribution of opportunities and resources, and frames the ways in which that distribution is interpreted. Whiteness holds sway over the very terms in which its own ascendency is understood and might be challenged.”39 These observations by Barbara J. Flagg open up debates on challenges that have been experienced in South Africa with regards white funding of Black art or art with Blackness-related content. The post-apartheid field of production merely bestowed on the arts and culture a symbolic emancipation, but not the requisite discourse to rupture foundations on which whiteness is predicated. In the context of this opera this practice allows internalised domineering material structures of whiteness that hide its role in the destruction of the Zulu Kingdom and the Zulu society. As seen in the opera such practices regenerate suppressed colonial-ethnographic tropes that went under during the heydays of the struggle against apartheid to resurface. Christopher Till observes in the case of South African museums and Black arts that financiers of arts often than not, impose influential directives in the constitution of arts. In many instances, their directives do not necessarily compliment and speak to the vision embodied by the government. It is a case of whoever pays the piper dictates the tune.40

Sakhiseni Yende and Vusabantu Ngema offer revealing understanding about the centrality of indlamu dance and the figure of the dancing warrior in the post-apartheid performance scenario. They claim that indlamu as a Zulu upper class culture has been used to create impressions that it is part of Zulu culture untarnished by Western influences, “probably because it is regarded as a touchstone of Zulu identity”.41 In the performance history of South Africa, indlamu and its dancing warriors have been used “as a tool to present a Zulu warrior/combatant as an ordered disciplined, submissive and obedient member of society”.42 Drawing from Gerrard Rooijakkers, they situate indlamu and the Zulu warrior culture within a social fiction theory of mythomania – the craze around heritage to highlight how the past is mobilised for all kinds of purposes that are non-innocent by local elites.43 Developing from Richard Schechner observations about the performance of traditional culture, Yende and Ngema affirm that the appropriation of heritage by the elite results in the transformation of tradition, often leading to its fundamental changes in function and significance. Not only do indlamu and the figure of the dancing warrior permeate theatre and opera locally and internationally, but these are also featured as packages for tourists, in tourists’ sites. While the dancing and the figure of the warrior evoke feelings of nostalgia for some, but increasingly, the heritage is for exoticisation. In addition, Yende and Ngema are of a view that in post-apartheid neoliberal and capitalist South African society, elites draw on indlamu as an internationally acclaimed heritage, to exploit its historical positioning for insidious and innocuous purposes that are associated with how these warriors and the military dance were understood traditionally and in the popular imagination; Zulu warriors are perceived to be submissive and obedient to their authorities. Therefore white financing of Black art where a heritage like a Zulu dance and a figure of the warrior are distinct, tend to confirm the view held by Flagg that, “Whiteness also carries the authority within the larger culture it dominates to set the terms on which every aspect of race is discussed and understood”.44 In the opera, Ziyankomo does not protest his conviction; in fact his belief in individualism makes him to choose death, thus he requests to entertain his audiences before he bows out of this world permanently. The idea of obedience in the face of death, and defiance of tradition by the younger generation directed as it were at an African masculinity is suggestive of stabilising agent forces at play meant to ensure maintenance of the status quo in the world outside the opera

The constitution of a Black opera narratives that eschews honest reflections about Black historical experiences in favour of detached, ahistorical representations make it difficult to read meanings suggestive of alternative knowledge production as argued by Walter Mignolo. Even though the theme of Ziyankomo is a universal one, it carries with it contingent histories and ethnographic perspectives that do not help it engage decoloniality practice. Its re-invention of tradition and questioning of heritage are suggestive that Ziyankomo is preoccupied with the culture of erasure; omitting historical facts in favour of exoticisation control, obfuscation of reality and maintenance of a supremacist status quo. By situating the opera within a plethora of other writings from the isiZulu literary tradition - to which the librettist belongs - the discussion demonstrated the intertextuality that scrutinised it for the historical detail it omitted from its representation of King Mpande’s courtly affairs.

Likewise, the opera’s focus on the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior is unsettling and point to other challenges brought about by white financing of Black (themed) art. Ziyankomo fits into a mould that has shaped South African performance history: as derived from the British exhibitions and as shaped by racial capitalism. In that, the British Exhibitions of the 1850s set the tone for racial relations for the rest of the British Empire to which South Africa was not immune as a colonial outpost. Performances that highlighted race difference became a staple for white financed productions and these practices have spilt over to the post-apartheid dispensation. Lack of suitable funding by the government in post-apartheid South Africa does not assist in overhauling the funding structure dominated by whiteness. Thus, the figure of the dancing Zulu warrior is read as attempts at controlling Black masculinities, seeing that the symbolic gesture of Zulu warriorhood points to Zulu philosophies of discipline, submissiveness and obedience - shadows of colonial-apartheid ideologies of acceptable Black masculinity. White financing of Black (themed) art betray desires for maintenance of Western domineering value systems. Core to the themes of control, recycled are problematic cultural determination sensibilities that re-entrench value systems that prop whiteness, white privilege and beneficiation.

Black History Month. “Human Exhibitions and the Origins of Racism.” B:M2024. Accessed August 10, 2024. https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/african-history/human-exhibitions-and-the-origins-of-racism/.

Blose, M. A. J. Uqomisa Mina-nje, Uqomisa Iliba. Johannesburg: Educum Publishers, 1968.

Canonici, N. N., and T. T. Cele. “Cetshwayo kaMpande in Zulu Literature.” Alternation 5, no. 2 (January 1998): 72–90.

Carton, Benedict, and Robert Morrell. “Zulu masculinities, warrior culture and stick fighting: Reassessing male violence and virtue in South Africa.” Journal of Southern African Studies 38, no. 1 (March 2012): 31–53.

David, Joshua Tolulope. “Representation, performative exchange and Afropolitanism: Rethinking Opera production in Nigeria Through The Magical Flute.” Cambridge Opera Journal (2025): 1–26.

Dhlomo, Herbert Isaac Ernest. “Cetshwayo.” In H. I. E. Dhlomo Collected Works, edited by Nick Visser and Tim Cousens. Johannesburg: Ravan Press,1985, 122–123.

Dhlomo, R. R. R. UCetshwayo. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1952.

Flagg, Barbara J.. “Whiteness as metaprivilege.” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 18, no. 1 (January 2005): 1–11. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol18/iss1/2.

Fleming, Tyler David. “‘King Kong, Bigger than Cape Town’: A History of a South African Musical.” PhD diss., University of Texas, 2009: 109–10.

Hlela, Moses and Nkosi, Christopher. Imithi Ephundliwe. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1968.

Ingraham, Mary, Joseph So, and Roy Moodley, eds. Opera in a multicultural world: Coloniality, culture, performance. Routledge, 2015.

Kennedy, Phillip A. “Mpande and the Zulu Kingship.” Journal of Natal and Zulu History 4, no. 1 (1981): 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02590123.1981.11964211.

Klawanski, Gillian. “The two Jewish women behind legendary Ipi Ntombi,” South African Jewish Report, December 12, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2025. https://www.sajr.co.za/the-two-jewish-women-behind-legendary-ipi-ntombi/

Knight, Ian. The Anatomy of the Zulu Army: From Shaka to Cetshwayo, 1818–1879. Barnsley, S. Yorkshire: Frontline Books, an imprint of Pen & Sword Books, 2015.

Latrell, Craig T. “Exotic dancing: Performing tribal and regional identities in East Malaysia's cultural villages.” TDR/The Drama Review 52, no. 4 (December 2008): 41–63. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2008.52.4.41.

Maposa, Sipokazi. “South Africa: UCarmen Given Thumbs-Up at star-studded premier.” Cape Argus, March 24, 2005, 1. Accessed July 25, 2025. https://allafrica.com/stories/200503240170.html.

Masina, Edward Muntu. “Zulu Perceptions and Reactions to the British Occupation of Land in Natal Colony and Zululand, 1850–1887: A Recapitulation Based on Surviving Oral and Written Sources.” PhD diss., University of Zululand, 2006.

Mhlambi, Innocentia J. “African heritage revealed through musical encounters and political ideologies in Cameron White’s Ouanga! and Reuben Tholakele Caluza and Herbert Isaac Ernest Dhlomo’s Moshoeshoe (South Africa).” In African Performance Arts and Political Acts, edited by Naomi André, Yolanda Covington-Ward, and Jendele Hungbo. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021, 106–27.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality.” Cultural studies 21, no. 2–3 (April 2007): 449–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Decoloniality and phenomenology: The geopolitics of knowing and epistemic/ontological colonial differences.” JSP: The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 32, no. 3 (2018): 360–87. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.32.3.0360.

Msimang, Christian Themba. Izulu Eladuma ESandlwana. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1976.

Ndelu, B. B. Mageba Lazihlonza. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1962.

Opera Africa ZA. “Ziyankomo and the Forbidden Fruit by Phelelani Mnomiya.” Uploaded May 20, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sCfM4gn-RE.

Paleker, Gaioonisa. “The State, Citizens and Control: Film and African Audiences in South Africa, 1910–1948.” Journal of Southern African Studies 40.2 (2014): 309–23.

Peterson, Bhekizizwe. Monarchs, Missionaries and African intellectuals: African Theatre and the Unmaking of Colonial Marginality. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Press, 2000.

Peimer, David. “Musical Travails in the British Empire.” The Oxford Handbook of the Global Stage Musical (2023): 158–89:166.

Phakathi, Mlungisi. “The land question in South Africa and the re-emergence of the nationalism of AmaZulu.” Journal of Nation-Building and Policy Studies 4.2 (2020): 103.

Pistorius, Juliana Mia. “Inhibiting Whiteness: The EON Group La Traviata 1956.” Cambridge Opera Journal 31, no. 1 (2019): 63–84. doi:10.1017/S0954586719000016.

Pierce, J. Lamar. “Programmatic risk-taking by American opera companies.” Journal of Cultural Economics 24, no. 1 (February 2000): 45–63.

Qureshi, Sadiah. “Meeting the Zulus: Displayed Peoples and the Shows of London, 1853–79.” In Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1910 edited by Sullivan, Jill A., John Plunkett and Joe Kember. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2012, 183–98.

Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality and modernity/rationality.” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (April 2007): 168–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

Roos, Hilde. “Opera Production in the Western Cape: Strategies in Search of Indigenisation.” PhD diss., Stellenbosch University, 2010.

Roos, Hilde. “Indigenisation and history: how opera in South Africa became South African opera.” Acta Academica 2012, no. sup-1 (January 2012): 117–55.

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press,1990.

Schechner, Richard. “From ritual to theatre and back: The structure/process of the efficacy-entertainment dyad.” Educational Theatre Journal 26, no. 4 (December 1974): 455–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3206608.

Staff Reporter. “Return of the Loincloth.” Mail and Guardian. August 15, 1997. https://mg.co.za/article/1997-08-15-return-of-the-loincloth/.

Stanton, Burke. “Musicking in the borders toward decolonizing methodologies.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 26, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 4–23. https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.26.1.02.

Tara, Firenzi. “The changing functions of traditional dance in Zulu society: 1830–Present.” The International journal of African historical studies 45.3 (2012): 403–25.

Tepe, Markus, and Pieter Vanhyusse. “A vote at the opera? The political economy of public theaters and orchestras in the German states.” European Journal of Political Economy 36, (September 2014): 254–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.09.003.

Till, Christopher. “Bridging the gap: researching art of Africa.” In Mintirho ya Vulavula: Arts, National Identities and Democracy, edited by Innocentia J. Mhlambi and Sandile Ngidi. South Africa: Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA), 2021, 348–385. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1k76jmn.20.

van der Hoven, Lena. “‘Opera has been Dying Down Slowly Even Before Covid-19 in South Africa’: Mapping South African Opera After 1994.” SAMUS: South African Music Studies 41–42, (February 2023): 255–93.

Vilakazi, B. W. Inkondlo KaZulu. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1935.

Vilakazi, B. W. Amal’Ezulu. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1945.

Yende, Sakhiseni Joseph, and Vusabantu Ngema. “Indlamu: An Image of Zulu Upper-Class Culture of the Past.” E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences 4, no. 3 (March 2023): 300–11. https://doi.org/10.38159/ehass.20234310.

Zungu, Marvin. “Voices of the Nation, Ziyankomo, The Forbidden Fruit: Ndabezitha Nans’ indaba and Ntab’ ezinhle.” Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMp7Vh0fD7M&list=RDJMp7Vh0fD7M&start_radio.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.