This article explores how institutional power dynamics have influenced the history and development of Yorùbá opera since the pre-colonial period. It highlights the indigenous roots of Yorùbá opera as a background for analyzing how three selected works from the colonial and post-colonial eras engage with issues of power. Focusing on Yorùbá Ronú, by Hubert Ogunde, Chaka by Akin Euba, and Funmilayo by Bode Omojola, the article examines how operatic elements such as plot, characterization, song, chant, pitch organization, and orchestration serve as essential components of an empowering intercultural operatic form. It places special emphasis on the significance of oríkì (praise chant) as a recurring narrative device in all three works, demonstrating how it is used to recall, re-enact, and re-signify historical events and figures, as well as weigh in on the storytelling. The article concludes with a reflection on the importance of these works in terms of the anti-colonial or decolonial strategies they embody.

Opera is African, and the politics of power and its consequences have shaped its poetics in Nigeria since ancient times. Focusing on the Yorùbá people of western Nigeria, this paper examines how institutional power dynamics have shaped the history and practice of opera since the pre-colonial era. In addition to discussing indigenous precolonial practices and their extension in new forms, I examine how Nigerian opera composers and theatre practitioners have engaged with the issue of power in their work. I discuss three categories of opera, the precolonial Agbégijó (masque theatre, whose history extends into centuries before the British colonial rule in Nigeria, and whose impact continues till now), the neo-traditional opera of the colonial and post-colonial era, and the more recent art music operas that bear significant affiliations with Western European operatic genres.

My interrogation of opera in this essay begins with a basic definition: the employment of music as a crucial component of theatrical musical storytelling. Pre-colonial and post-colonial Yorùbá operas often combine music, chant, dance, speech-based dialogues, instrumental music, acting, and dramatic narratives in the explication and performance of dramatic plots. A crucial and recurring tool of narrativity in such operas is oríkì (praise chant), defined by a singing-speaking vocalism, typically performed as panegyric texts, often historical. In praising an individual, for example, oríkì performers interpolate the achievements of the person’s ancestors along with the person’s praise, generating a historically cumulative form. In Yorùbá society, every deity, person, family, town, institution, etc. has a compendium of oríkì. So too are Olodumare (the Yorùbá God of the universe) and all Yorùbá deities.1 My interrogation of oríkì in this essay follows two approaches: as a specific type of narration, one that focuses on textual panegyrics, as well as a type of vocalism, defined by the Yorùbá recitative chanting. It is not in all cases that recitative chanting is praise oriented.

In societies with a history of colonial rule, artistic expressions must undergo significant experimentation, as creators of new forms and their audiences have to grapple with how to re-interpret old forms in new ways in a transitioning society. My discussion tackles these issues historically and analytically. I examine the precolonial roots of opera in Western Nigeria, the impact of European musical and theatrical practices, and analyse the types of choices and decisions that inform the works of 20th- and 21st-century Yorùbá operatic composers. The operas that I discuss are Hubert Ogunde’s Yorùbá Ronú, Akin Euba’s Chaka, and my most recent opera, Funmilayo. All these operas explore the issues of power in two ways: as a focus of plot and in terms of how they resist, or rework Western operatic forms or theatrical conventions associated with the “colonial matrix of power.”2 My conclusion reflects on the significance of these works in terms of the anti-colonial or decolonial strategies they propose. As a background to my analysis, I begin with a brief discussion of critical terms, namely, opera, narrativity, and oríkì.

Western scholars, performers, and composers often view opera primarily through the lens of its European history and tradition. However, despite the global influence of Western opera, largely due to colonialism, and while the term “opera" originates from Italy, the essential use of music as a means of storytelling and dramatic performance is not exclusive to the Western world. Additionally, as history demonstrates, opera traditions in Europe itself have varied significantly in form and style, as well as in the varied scope and use of music. History also shows that opera has followed or adapted to specific national traditions and aspirations, and that there is no singular understanding of opera, despite the global predominance of the Eurocentric notion of opera.3 As Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka noted in his essay "African traditions at home in the Opera House," the “alliance” between music, drama, dance, and spectacle, essential to all operatic practices, including those of the West, existed before the onset of colonialism.4 Opera has never been a “foreigner” in Africa.

The indigenous pre-colonial Yorùbá Agbégijó is different, of course, from the European styles and forms discussed above. It, however, represents yet another example of an operatic tradition. As I explain below, Western-influenced operatic performances of the colonial and post-colonial era often draw on the elements of Agbégijó to create new intercultural forms that illustrate how new African compositions redefine opera in ways that may affirm, invoke, or re-signify both Western and African cultural and musical premises of opera. In extending the range of operatic narratives and re-signifying them beyond what typifies Western operatic genres, new African operas are shaped in response to the dynamics of colonial domination. The anti-colonial political agenda of new African operas is illustrated in the works of the Egyptian composer Sayed Darwish (1892–1923), who, like his operettas, “was very much connected to the political resistance movement against British domination.”5 Darwish’s interrogation of power through opera was not only against external forces. It was also responsive to the dictatorial politics of Egyptian leaders. As Nora Amin further observes, “Darwish will always remain the most powerful evidence that music can decolonize, unite and revolutionize, even in the face of continuous interruption, manipulation and state control of consecutive dictatorial regimes.”6 The conception of new African opera to redress and challenge the politics of colonialism has also been discussed by Moses Nii-Dortey (2012) in his discussion of The Lost Fishermen, an opera by the Ghanaian composer, Saka Acquaye.7

As mentioned above and explained below, oríkì has featured in Yorùbá theatrical performances from time immemorial, playing a crucial role in defining dramatic narratives. Kofi Agawu, in explaining the "logic of progression” that marks musical expressions, observes that the “idea that music has the capacity to narrate or to embody a narrative, or that we can impose a narrative account on the collective events of a musical composition, speaks not only to an intrinsic aspect of temporal structuring but to a basic need to understand succession coherently”8 Narrativity denotes the inherent orientation of a musical performance to self-define the premises of its efficacy and coherence based on the convention of practice to which it is affiliated and as gleaned by listeners. Such premises are both internal and external. Teleological, discursive, and rhetorical devices activated within the narrative process itself are complemented by extra-musical references, for example, the historical, biographical, and social elements that form part of the thematic concerns of the narration. As Richard Taruskin has observed, “Narrating is not simply a tale but a telling. and whoever or whatever is designed as a teller is a “voice.”9 His observation reminds us of critical components of the narrative enterprise, namely, the “constituents of the narrated (the “what” that is represented), those of the narrating (the way in which the “what” is represented), and the principles regulating their modes of combination.”10 Added to this is the cultural provenance of a narrative practice that provides the background for understanding how new variants (and specific iterations) of a narrative genre overlap with, deviate from, or revise its historically abstracted form.11

Abiola Irele (1993) draws attention to the multi-dimensional power of African oral narrative forms like oríkì. He describes narrative expressions as a process of “reconstitution” in which the elements of history interface with those of form: a narrator must decide on the aspects of a story to be reconstituted, while also pondering the discursive strategies to employ.12 The stories or (the content) that are recalled in a narrative act and the imaginative ways they are told (how they are arranged and the ordering principles followed) could be schematised as creatively ordered facts, marked by two complementary impulses: the will to factualize (that is, the conveying of experiences and events as factually as possible) and the will to fictionalize (that is, the creative retelling of story). The latter is a process of recasting, based on certain organisational premises and oriented toward reflection and re-symbolizing, and in ways that are attributive of new meanings. The factional and the fictional are, of course, not mutually exclusive, although a particular narrative may emphasize one approach over the other: one may emphasize plot narrative, while the other may emphasize a textual or structural approach. The two components reflect distinctions that are “analogous to that between diegesis and exegesis.”13

These basic perspectives of narrativity provide a background for understanding the concept and practice of oríkì in Yorùbá performance. Oríkì genres exist as a body of variable text, a storytelling form marked by certain techniques of rendition, the practice of which dates back hundreds of years. But oríkì is not just a product of history. It is also a medium through which history is narrated and constructed, performed, documented, or fictionalized through creative or artistic interrogation. On the one hand, the performative and textual elements that define it have over the years coalesced into a performance style, while on the other, oríkì often interrogates historical events in the composing of its panegyric or non-panegyric text. In terms of its textual and discursive elements, oríkì is performed in a specific type of singing-speaking voice and features sequential itemisation of the text and poetic devices as vital elements of dramatic storytelling. However, as I explain below, its narrative significance tends to lie chiefly in how it is performed to recall, re-enact, and re-signify history as relevant to a specific context of its performance.

The Agbégijó dates to at least the 14th century, developed as part of palace activities of the ancient Yorùbá Ò̩yó Kingdom. Its development followed three main historical and artistic phases, namely, ritual, festival, and theatre, each of which corresponded with the reign of specific kings. For example, the ritual phase had become institutionalized by the mid-16th century during the reign of Alaafin Ò̩finran c. 1544). As Adedeji has extensively discussed, it existed as Egungun (“masquerade”) performances that were enacted as ancestor-venerating theatre.14 The festival theatre expanded the scope of the ritual phase with a larger retinue of masked performers, known as Eegu'nla (“lineage-masquerades”), each of which was affiliated with a specific family. The Eegu'nla performance was a “dance-drama” supported by choral chants (based on oríkì) and accompanied by bàtá drums.15 Drummers and chanters were drawn from O̩mo̩lé (family members) of each of the participating masquerades.16 By the late sixteenth century, these performances had evolved into a semi-independent theatre that could be re-staged as a command performance featuring masked dancers and actors (known as Ò̩jè̩ performers) and accompanied by drummers. In the 18th century, the Ò̩jè̩ music-dance-drum performance received great support from Alaafin Abiodun (who reigned from 1770–1789). He helped to stimulate specialization in various aspects of “craft-guild” arts.17 Two prominent 18th-century British explorers, Hugh Clapperton and Richard Lander, witnessed the Agbégijó and reported about it in their travelogues.18 An account of their experience is summarized by Adedeji as follows: “To mark their seven weeks stay in Old Oyo Katunga, the capital of the Oyo Yorùbá empire, the Alaafin (king) of Oyo invited his guests to see performances provided by one of the travelling troupes which at that time was waiting on the King’s pleasure. The time was Wednesday, February 22, 1826.”19

This brief history of Agbégijó highlights the triadic significance of operatic performances in pre-colonial Yorùbá societies: asserting the power of the King, serving religious purposes, and providing a medium for community-wide participation. In its democratic expansion to include the participation of families, Agbégijó helped to strengthen the bond between the king and his subjects, functioning as a tool for the sustenance of the institution of kingship in Yorùbá society. The history also draws attention to the significance of the Yorùbá Mask as a work of art and a religious emblem that connects the living with the supernatural. Music exists as both chant and song, performed as call-responsorial singing and as a singing-speaking voicing in the form of oríkì (panegyric) and the “orílà” (totem). Dialogue tends to be scanty, while dance helps to generate excitement and a means for explicating dramatic spectacle (idán), satire (è̩fè̩), or “reprobation” as obtainable within the Yorùbá cosmology.20 The Agbégijó tradition continues today as detailed in my ethnographic account of an event that I witnessed on July 15, 2007, in Oshogbo, Western Nigeria.21 One of the Agbégijó oríkì that I recorded during my research in Oshogbo is provided below. It was performed by a Dùndún drummer who later recited the words of his “talking” drum to me, as shown in the Yorùbá transcription and the English translation.22

This short excerpt narrates the significance of dance in the Agbégijó mask theatre. The chanter urges the masquerade (referred to as “My Father”) to dance, wonders why he is reluctant to do so, and asks whether he has been fed properly with his favourite food, yam porridge. The language of the chant is poetic, elevated with symbolisms that draw on animals and the tools of everyday life. For example, the lines “The anterior of the frog images that of the bullfrog” and “The tail of the needle pierces neatly into the dress” emphasize the iconic relationship between dance and mask, a compatibility that is further articulated in the concluding line, viz., “To not dance is unthinkable.” By referring to the masquerade as “My father,” the chanter reminds the audience of the cultural belief surrounding the mask performance in Yorùbá society—the veneration of ancestors, whose counsel and knowledge could be invoked through ritualised performances. Masquerades are manifestations and representations of ancestral voices. This excerpt highlights the multiple foci of oríkì: the instigation of an entertaining performance, reflection on the aesthetics of Agbégijó mask theatre, and historical contextualization of the performance as an agelong medium for the veneration of ancestors in Yorùbá society.

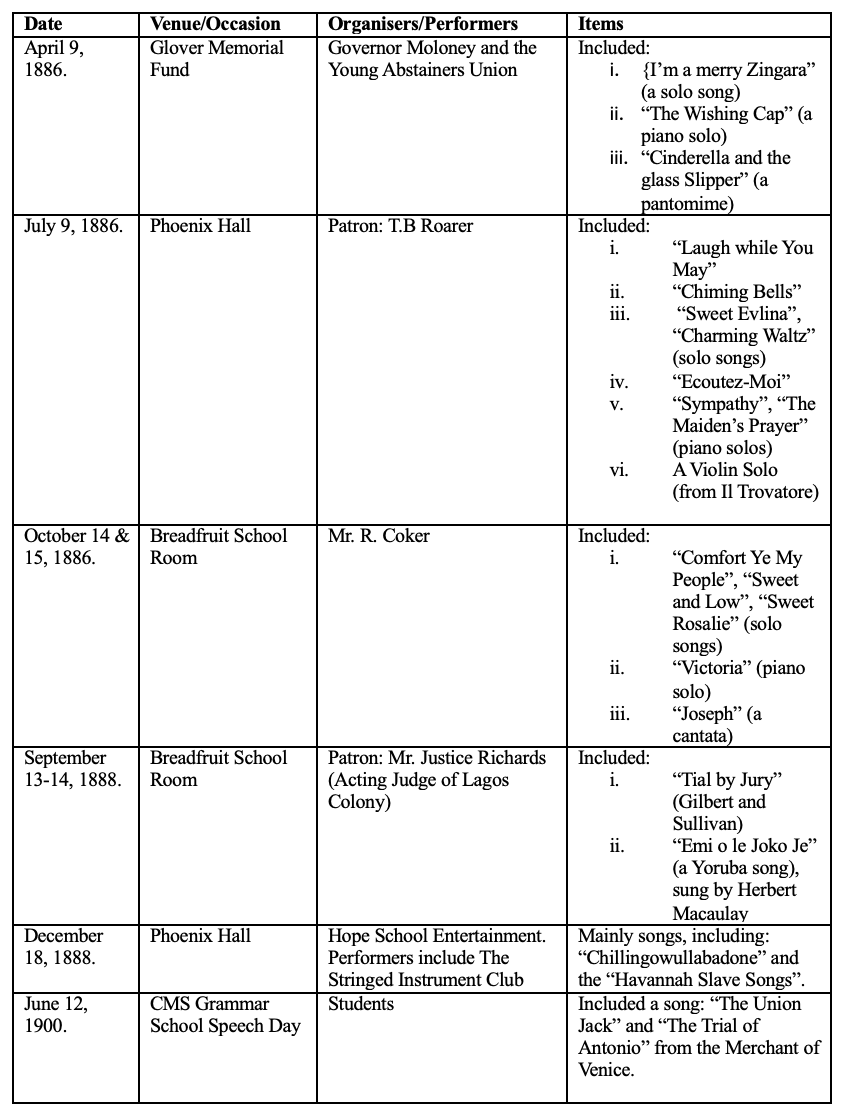

By the last two decades of the 19th century, the cultural impact of British colonial rule was already being keenly felt in Nigeria, particularly in cities like Lagos and Abeokuta, where Christianity had begun to take root. British hymnody was introduced through the Church, and European classical music was taught and performed at missionary schools. Alongside the activities of missionaries were those of philanthropic organisations aligned with the colonial elite, who organised European concerts that included theatrical performances and helped to strengthen the influence of British Victorian-era culture in Nigeria. The concerts were aimed at the elite—both British and Nigerian—and were often widely reported in the press. For example, one such concert was reported by The African Times on May 1, 1876. It was organized by Lt. Governor Lees to welcome the British Consul in Lagos, Sir William Hewett, who had just returned from a tour of Ekiti in Western Nigeria. The newspaper reported, “All the principal people, native as well as European, were there.”23 As shown in Table I, the concerts featured a variety of shows, including pantomimes (such as "Cinderella and the Glass Slipper"), instrumental solo performances, musico-dramatic works (like Handel’s oratorio, The Messiah), musical excerpts based on Shakespeare (for instance, The Trial of Antonio-from The Merchant of Venice), Gilbert-Sullivan operas (like Trial by Jury), and many more. Although these events occurred in late 19th-century Nigeria, their historical impact would endure beyond the end of colonial rule in 1960. The ongoing influence of colonialist culture, as evidenced by the continued relevance of Victorian-era performance traditions in Nigeria, highlights the ironic ways colonial domination operates: its cultural and political significance is often sustained by imperialist foundations long after colonial rule has ended and long after the colonising country may have progressed to another cultural phase. A significant outcome of these shows was that Nigerian dramatists and composers began to develop proscenium-type performances, in which audiences and performers are more distinctly separated from one another, contrasting with indigenous Yorùbá circular spaces where “there is always ample room for spectators to join professional performers, either by singing refrains or by dancing.”24 Yorùbá folk opera frequently incorporates Western stagecraft techniques, such as set designs, lighting, etc. Neo-traditional opera25, despite its primarily Yorùbá form, may also utilise Western instrumentation, pitch systems reflecting the effects of Western tonality, and the “number opera” format reminiscent of the British Gilbert-Sullivan operas.

Despite such Western influences, Yorùbá neo-folk opera composers were conscious of the need to emphasise indigenous dramatic elements, an approach that aligned with the anti-colonial agenda of the political leaders of the time. As I have explained in another publication, in their resistance against colonial rule in Nigeria, Nigerian leaders of the colonial era realised that the struggle for political and economic independence must exist in tandem with cultural nationalism.26 Euba defines the new folk opera form as “multi-artistic” dramatic performance featuring music, dance, costume, and poetry with strong “imprints of traditional music.” The close affinity between it and their “traditional prototypes” is what makes them neo-traditional forms.27 And describing its practice, Euba adds that the “typical composer is highly knowledgeable about traditional culture and modern Nigerian society. It is usual for a composer to lead his (sic) own performing company and to have members of his family as core personnel in the company.”28 He also explained that the “typical composer is also the librettist, principal actor, artistic director, and producer, and very often, one of his wives plays the female lead.”29 These characteristics apply generally to the three doyens of the Yorùbá folk opera, Hubert Ogunde (1916–1990), Kola Ogunmola (1925–1973), and Duro Ladipo (1931–1978), all of whom played active roles in shaping the development of the new form during and beyond the colonial era.30 They all utilised oríkì as a crucial component of their operas. My discussion here concentrates on Ogunde.

Born in 1916, Ogunde is credited with establishing the first professional theatre company in Nigeria and is regarded as the “father of modern Yoruba theatre.”31 His first company, the African Music Research Party, established in 1945, was dedicated to creating dramatic works that rely significantly on indigenous Yorùbá music and dance resources. He also firmly established himself as part of the nationalist movement that campaigned against colonial rule. Although Ogunde was not a politician, his dramatic works often comment on political and non-political issues that are topical to the politics of nationalism. For example, political themes are the focus of “Strike and Hunger” and “Bread and Bullet”, while ethical and philosophical themes as obtained within a Yorùbá worldview and portrayed through myths and legends are expressed in Aropin N’teniyan (To Despise is Human, 1964), “Aye” (This World! 1972), and Jayesinmi (Let Peace Reign, a film, 1981).

But his most popular work is a political satire, titled “Yorùbá Ronú” (1964). Composed and written in 1964 (just four years after the end of British colonial rule), Yorùbá Ronú is based on a political crisis emanating from the dispute between King Fiwajoye and his rebellious deputy, Ekeji Oye, who plots to overthrow the legitimate rule of his boss.32 The opera is also a parody of the tumultuous relationship between Obafemi Awolowo, Premier of Western Nigeria from 1954–1959, and his deputy Ladoke Akintola. Thus, although the story is historical in its origins, it is contemporaneous with a simmering political crisis of the early years of Nigeria’s independence following the end of British colonial rule. Historically speaking, the plot recalls the 19th-century intrigues of Afonja, a war general who plotted to overthrow the Alaafin Aole of the Oyo Kingdom. The work interpolates drumming, chant, and song, with a predominantly spoken dialogue. The “Yorùbá Ronú” era marked an important phase of the Yorùbá Traveling Theatre tradition and a moment for experimenting with a new intercultural operatic form adaptable to a Western-type performance space and relevant to current social life and political development.33 For example, the recall of ancient history to reflect on contemporary political development models Ogunde’s approach to the use of music in the opera. Also, the interpolation of songs within the dramatic plot in Yorùbá Ronú recalls the impact of the number opera form of the Gilbert-Sullivan operas. This is paralleled by the use of oríkì, Yorùbá songs and dialogues, dances, and costumes. Many of these elements are illustrated in the theme song of the opera (also titled Yorùbá Ronú), performed by a male solo (Hubert Ogunde) and supported by a female chorus.

Like most Yorùbá folk operas, Ogunde’s Yorùbá Ronú is not scored. It does not employ Western staff notation. It was never conceived as a notated composition, and my discussion does not employ any form of music notation transcription. My discussion relies on song lyrics, an English translation, and a recording of the song, accessible through the link I provide in the footnote.

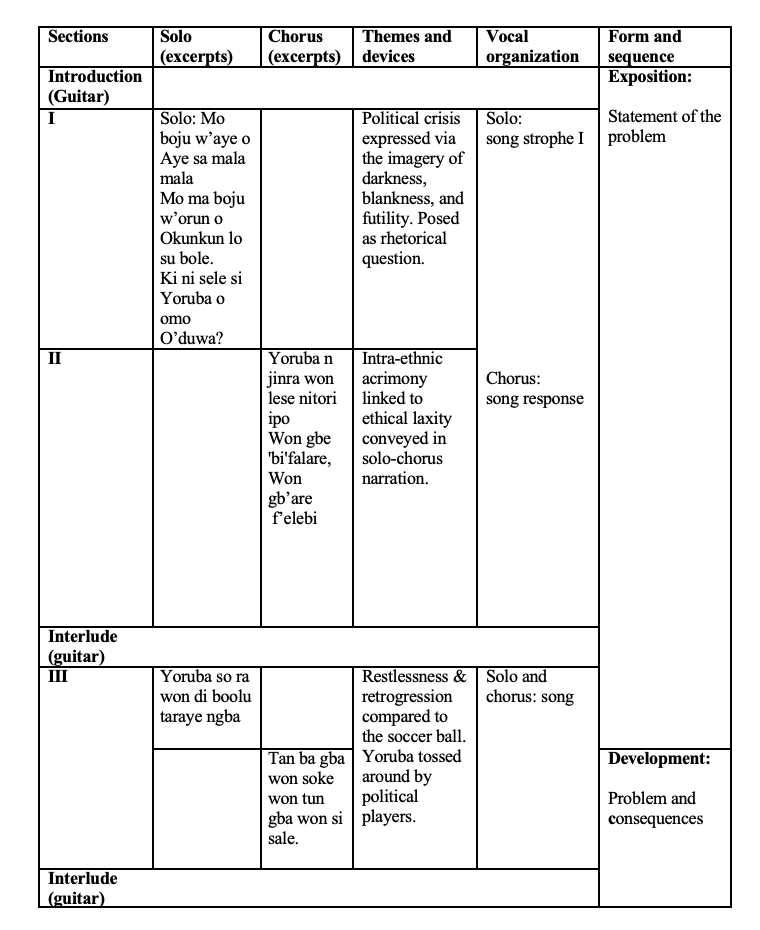

The song describes the political darkness that envelopes Western Nigeria, critiques the unethical behaviour of politicians, and calls for sober reflection. As shown in the Yorùbá song-text and the English translation, underlining the philosophical index of the song is the use of the imagery of darkness (that envelopes the heavens) and the blankness and futility of life, the invocation of Yorùbá ancestral figures (for example, Oduduwa), and the rhetorical use of proverbs (see excerpts and Table 2 below, and the full song with English translation in the appendix).34

Interpolated into the stanzaic/strophic form is a solo-chorus conversational technique. As shown in Table 2, the evolving relationship between the male soloist and the female chorus is crucial to the telling of the story of the political crisis that engulfed the Yorùbá nation in the 1860s. In the early moments, the chorus expands on the expository statement of the solo part by providing answers that develop the story. And because each new line of the song text tends to generate its melody, the development of the storyline guarantees musical continuity, as can be observed by listening to the recording.35 As the song progresses, the relationship between solo and chorus becomes more dynamic and interactive through the overlapping of parts, especially in the final segment of the song, where the musical material also changes to activate closure to the song. As shown in Table 2, the male solo changes into an oríkì text that extols and invokes the goddess of the earth, Ilè̩. The convergence of the solo-chorus overlaps and the layering of song over invocatory oríkì text help to impart dramatic intensity and a sense of urgency that help to emphasize the message of the song—the political crisis in Western Nigeria.

Ogunde’s use of the guitar exists as part of an intercultural style informed by both Western and Yorùbá elements. An emotive-sounding guitar introduces the song, functions as interludes between the stanzas, and provides a brief cadential closure (see Table 2). As can be heard in the recording, the guitar’s Western-type tonic-dominant note oscillations complement the ostinato patterns of the percussion. Both the guitar and the percussion function minimally and unobtrusively, in ways that defer to the musico-dramatic narration of the vocal part. Singing is generally in unison, featuring parallel harmonies only at cadential points. Although cadential harmony in thirds are not uncommon in indigenous Yorùbá singing, their use here alongside the dominant-tonic ostinato punctuation of the guitars, both elements of which are minimalist (that is, lacking a sustained sense of harmonic or rhythmic progression), could also be heard as a residue of tonal harmony as practiced in the British Christian church in Nigeria.36 The use of a Western-style number opera, residues of Western tonality, the guitar, and a proscenium-type presentation (rather than indigenous Yorùbá circular performance spaces), interfaced with African song and chant tradition, percussion, Yorùbá poetic devices and narrative processes, highlight how composers of the neo-traditional folk opera assert indigenous elements without completely breaking away from colonial influences.

Nigerian composers who studied Western art music have been developing a new operatic tradition that departs significantly from the neo-traditional genre. The list of such composers and examples of their works include Adam Fiberessima (Opu Jaja), Samuel Akpabot (Jaja of Opobo, 1972), Lazarus Ekwueme (A Night in Bethlehem), Meki Nzewi (A Drop of Honey) Akin Euba (Chaka, 1970), and Bode Omojola (Funmilayo, 2023).37 My examination of this category centres on two works, Chaka and Funmilayo, both of which also incorporate Yorùbá indigenous operatic resources, including Oríkì, and explore the theme of political power. I have discussed Chaka extensively in another publication. My discussion of it here is therefore brief, used mainly to highlight its historical significance and how it functions as a precedent for my own work.38

Akin Euba (1935–2020) studied piano and the basics of classical music at CMS Grammar School in Lagos before moving to England and the United States to study Western classical music. Like many African composers, moments of critical reflection on his work as a composer followed his encounter with ethnomusicology, first at UCLA as a master's student and later as a doctoral student studying with Kwabena Nketia at the University of Ghana. Perhaps more than any other African composer, he advocated for an African art music idiom that draws on indigenous resources to empower African composers in their efforts to forge an alternative art music tradition to the one imposed on Africa through colonialism. Charting an alternative compositional path does not necessarily imply a total rejection of European elements. Indeed, the concepts and approaches he proposes often revolve around a pragmatic intercultural approach that acknowledges the historical reality of colonialism. They include African pianism, which emphasizes how the European piano could be used to simulate indigenous African elements, and creative ethnomusicology, which focuses on how research into African music could empower an African composer in the pursuit of an alternative art music modernism.39 Euba also explored the possibility of Africanising the European symphony by integrating traditional African instruments with European ones, as illustrated in Chaka, a style element he describes as follows: “The African identity of the work may be observed first in the use of various African traditional instruments, employed in a polyrhythmic style typical of African culture. Secondly, the first three ostinato sections of the prelude are characterized by bell patterns derived from a standard pattern commonly used in many parts of Africa, the adowa dance of the Ashanti of Ghana, and the atsiagbekor dance of the Ewe (also of Ghana).”40

Akin Euba’s Chaka (for soloists, Yorùbá chanter, chorus, dancers, and an ensemble of Western and African instruments) was composed in 1970 but reworked several times. My discussion is based on the final version of the work as performed by the Birmingham Opera Company in England in 1998.41 The plot of the opera examines the theme of political power as obtained within the colonial history of South Africa. It focuses on the activities of King Zulu, the Chaka (1787–1828), who ruled Zulu land in present-day South Africa. The libretto is based on Léopold Senghor’s account of the life of the king as narrated in his dramatic poem titled Chaka. The main characters of the opera are Chaka (Bass), White Voice (tenor), Noliwe (Chaka’s bride-to-be, soprano), Leader of the chorus (bass), Praise Chanter (preferably female), Chorus, and Dancers. As Euba explains, “Chaka was one of the first Africans to take a stand against what later became apartheid, and for his courageous act, he died a martyr not only for his own people but for all Africans.”42

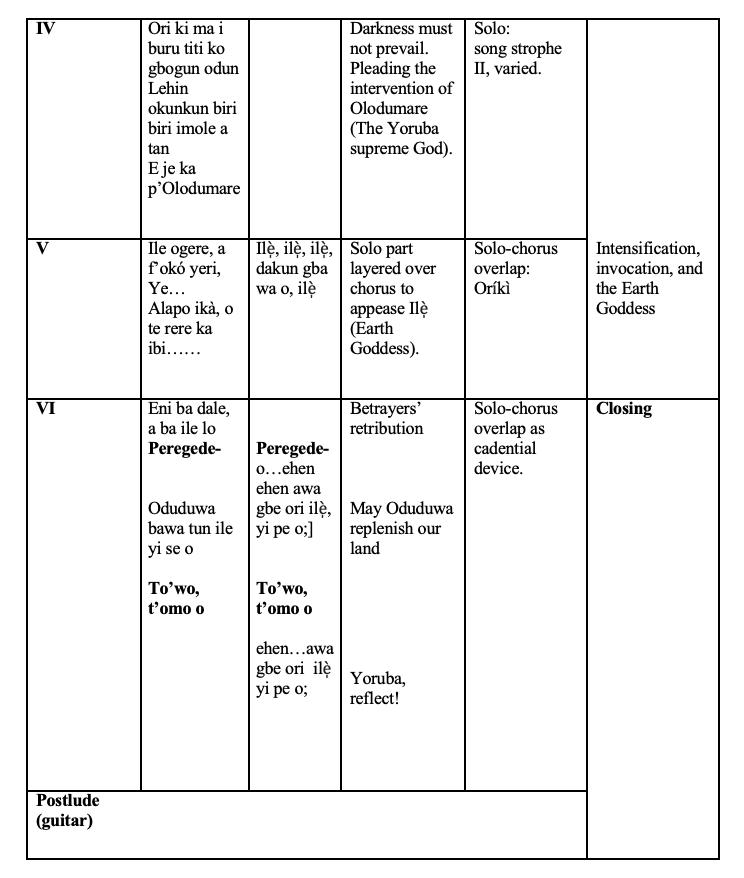

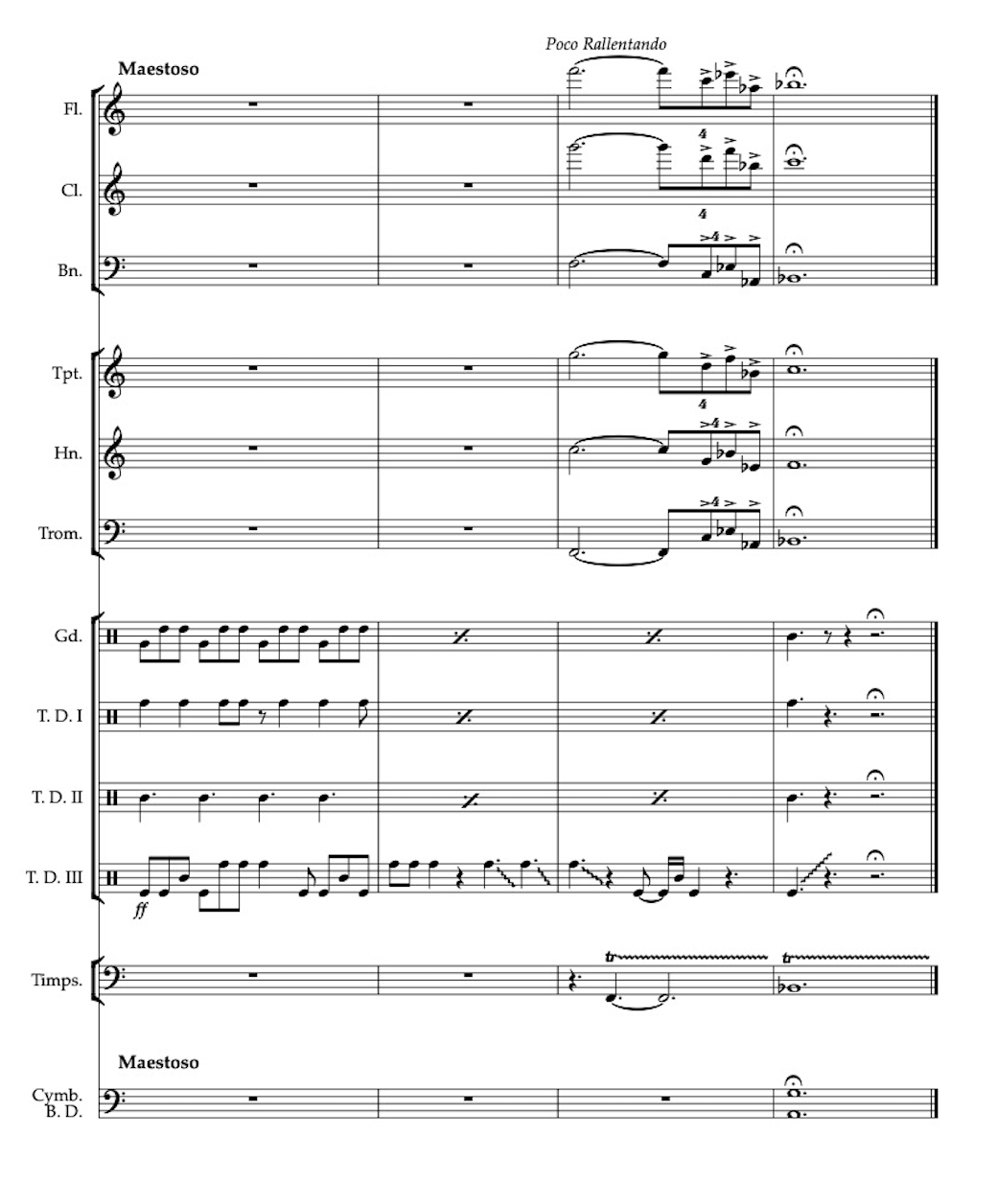

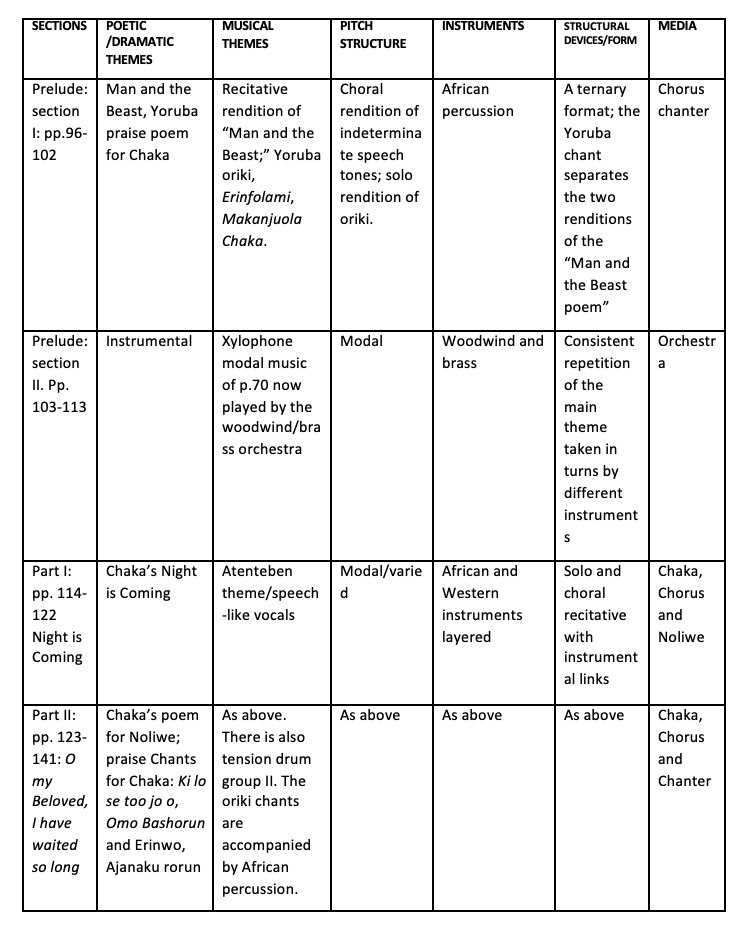

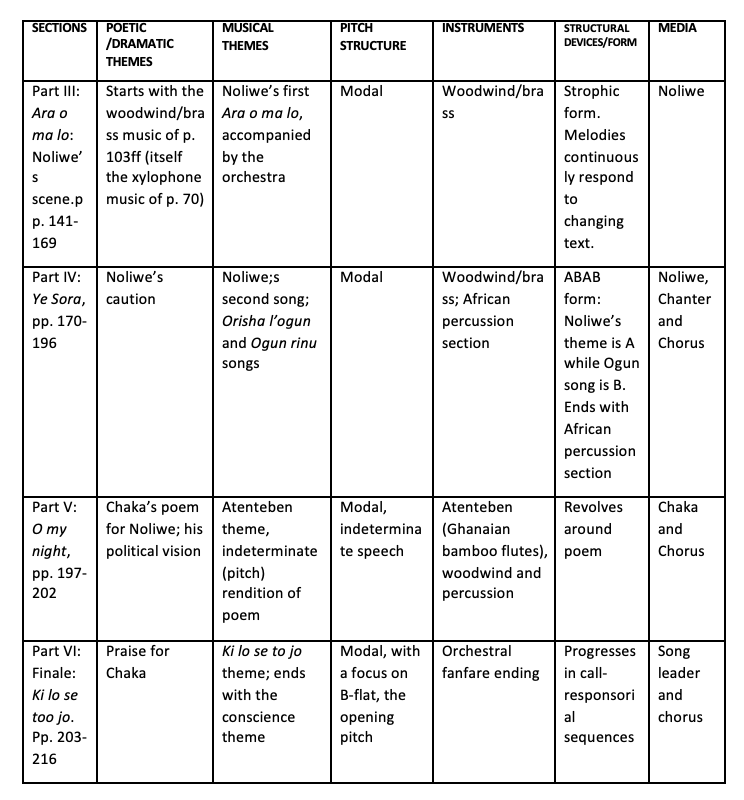

The opera retains the two sections of Senghor’s poem, Chants I & II. The instrumentation of Chaka is intercultural, consisting of Western and African instruments. Euba’s orchestration is informed by his desire to evoke the Yorùbá festival performance in which different ensembles perform close to one another in “uncoordinated ways.” In “Chaka,” configurations of ensembles include the xylophone group, the atenteben (Ghanaian flute) group, the dùndún hourglass tension group, and the Western woodwind-brass group. As shown in Table 3, which focuses on Chant II, these groups often relieve one another in weighing in on the storyline or supporting different characters. This technique is anticipated in the opening moments of the prelude where brass instruments, the double bass and African percussion, appear in succession as part of the composer’s objective to highlight the distinct instrumental “voices” of the opera, (Figure 1). At critical moments, such individual units are brought together for dramatic purposes, as is the case in the opera’s finale, where the woodwind, brass, timpani and cymbals combine with the African percussion group for an emphatic ending, (Figure 2).

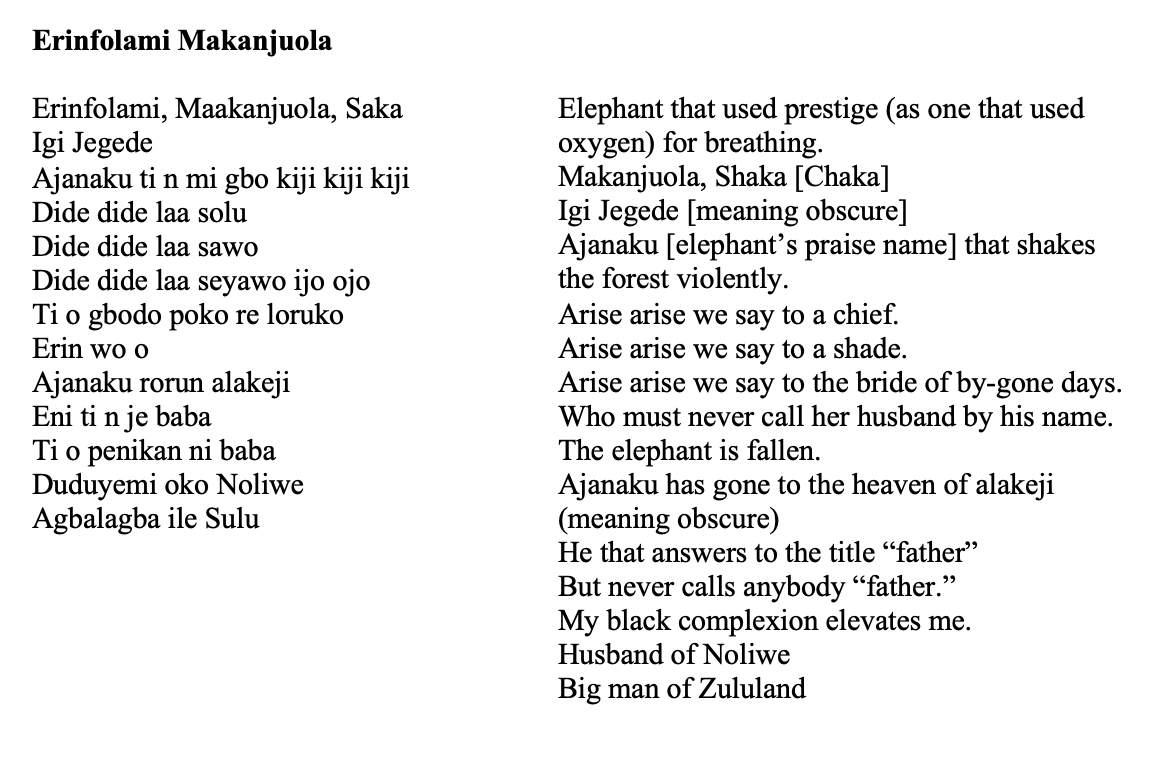

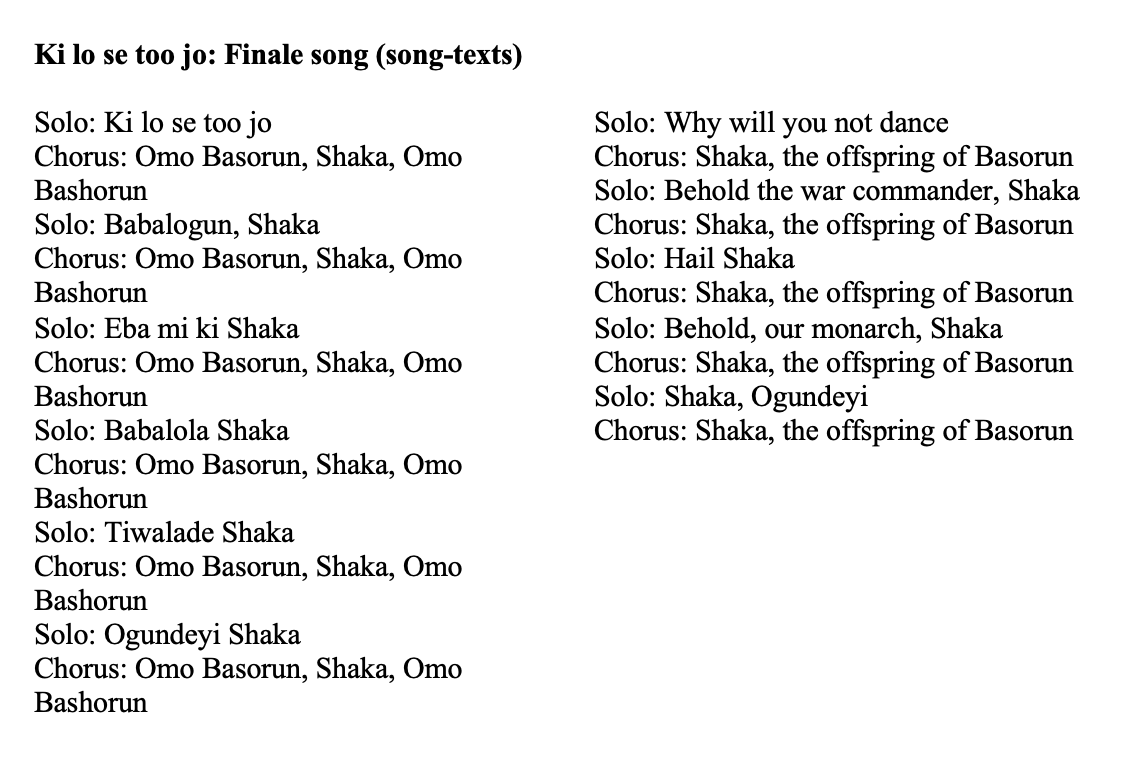

The intercultural instrumentation of the opera is echoed in its diverse vocal styles, combining Western recitative (for example, the poem “Man and the Beast,” rendered in a Western recitative style) and Yorùbá oríkì chanting, as illustrated in “Erinfolami Makanjuola” in honor of Chaka at the beginning of Chant II (see Table 3). The opera employs the aleatoric technique (for example, by asking singers to select their own notes and rhythmic patterns) and uses leitmotifs to index and identify characters (Figures 3, 4, 5), recalling a similar technique by Richard Wagner. African call-and-response procedures feature prominently too as illustrated in the final song, Ki lo se too jo (see text below).

Two parallel themes, praise and reprehension, continuously recur in the narration of the story of Chaka, an interweave that underlines the grand narrative impetus of the opera. Chaka is often treated as a hero to negate White Voice’s representation of him as a bloodthirsty tyrant. The musical means for the veneration of Chaka is the Yorùbá oríkì, re-signified to extol Chaka in ways that clearly reveal the composer’s political objective. Chaka’s portrayal as a heroic anti-colonial activist is expressed in the oríkì titled “Erinfolami Makanjuola,” taken from the repertoire of two powerful Yorùbá kings, Oba (king) Adetoyese Laoye (Timi of Ede) and Oba Adesoji Aderemi (Ooni of Ife). In the re-contextualized version, the chanter compares Chaka to an elephant, nudging him to rise, fight, and lead his people against British colonial rule. The comparison of a South African leader to the Yorùbá hero, Makanjuola, is inherently pan-African, linking two biographical entities thousands of kilometres away from one another. In the chant, Chaka is Yorùbálized as Sulu.

Furthermore, in the finale, a rallying call-and-response song with the English title, “Why Will You Not Dance, Chaka,” but sung in Yorùbá, Chaka is hailed as a Yorùbá prime minister (Bashorun),43 a monarchical personality (Tiwalade). Unlike the Agbégijó performance that I discussed earlier, in which dance is invoked for entertainment purposes, dance in this finale is re-signified in political terms. As a symbol of a Yorùbá warrior (Babalogun) and war deity (Ogundeyi), Chaka is urged to rise and dance, even in death.

In addition to articulating a political agenda and empowering characterisation, as these examples demonstrate, oríkì, in its recurrences, performs a striking structural role within the overall form of the opera. As shown in Table 3, which is based on Chant II, the second main part of the opera, it is interpolated with a European-type recitative to articulate a simple ternary division in the opening moment of the opera. The interpolation also helps expand the pitch horizons of the opera beyond modal and atonal pitch organisational systems. The juxtaposition of the two vocal styles articulates the conflictual relationship between the two protagonists, White Voice and Chaka, thus sustaining the parallel themes (praise and reprehension) that I mentioned earlier. As the opera progresses toward the end, oríkì, supported by African drumming, brass instruments, and complemented by Yorùbá call and response singing, is employed to celebrate Chaka’s heroism, culminating in significant drama in the finale in a manner that emphatically underscores the anti-colonial representation of Chaka in the opera.

As a disciple of Akin Euba, I have been actively engaging with similar issues that he explored. For example, I have composed a series of piano works conceived along the lines of African pianism44 and have written and directed African operatic works that draw on indigenous resources as part of my commitment to decolonising art music practice in Nigeria. In addition to studying Western classical music within and outside Nigeria, I started with informal piano lessons at Christ’s School Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria, followed by a music degree at the University of Nigeria, an MA at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and ultimately obtained my PhD at the University of Leicester in England. Parallel to my formal Western music education, I grew up participating in indigenous musical traditions at secular and sacred ceremonies in Western Nigeria, an experience that continues to this day. I have also conducted ethnographic research into indigenous Yorùbá musical traditions, about which I have produced many academic publications. This bi-musical path provides the foundation for my experiments in integrating Western and African elements in my composition, as illustrated in Funmilayo.

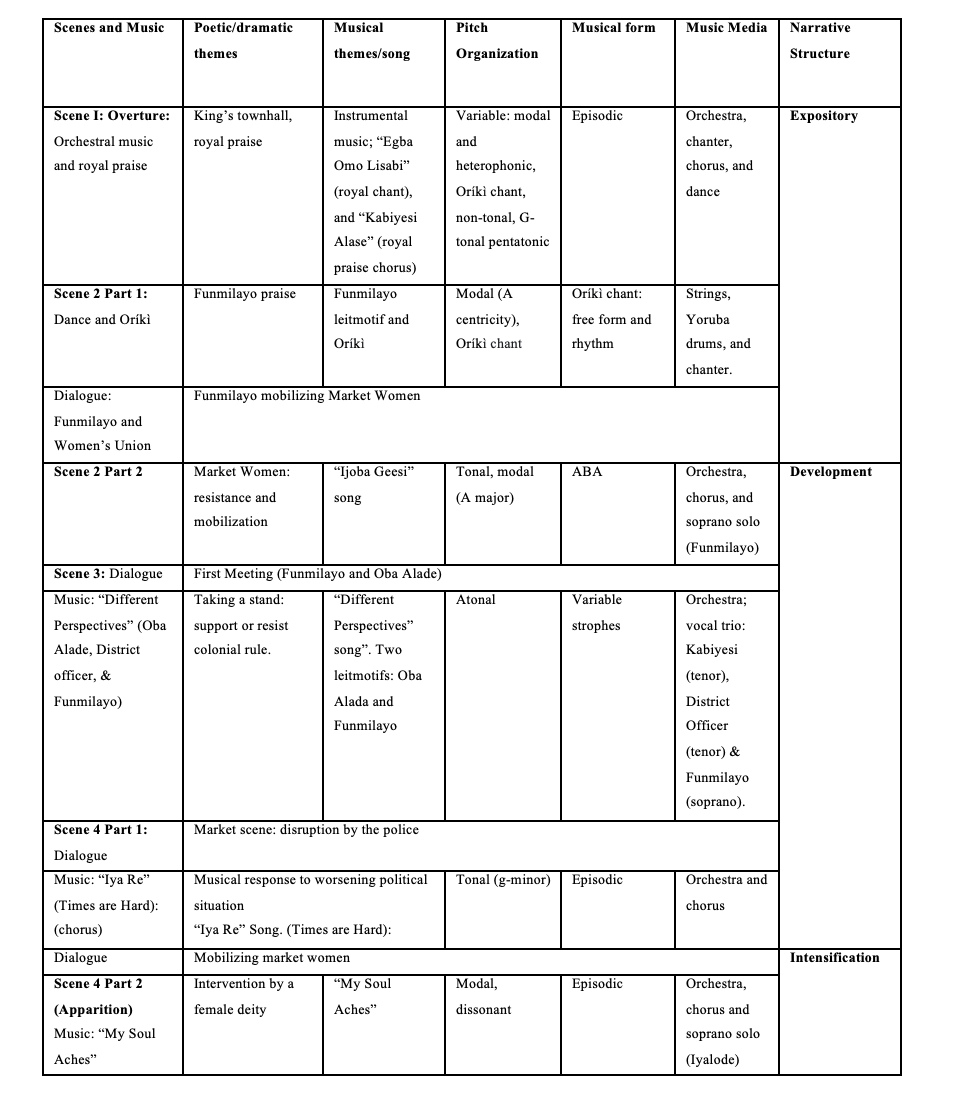

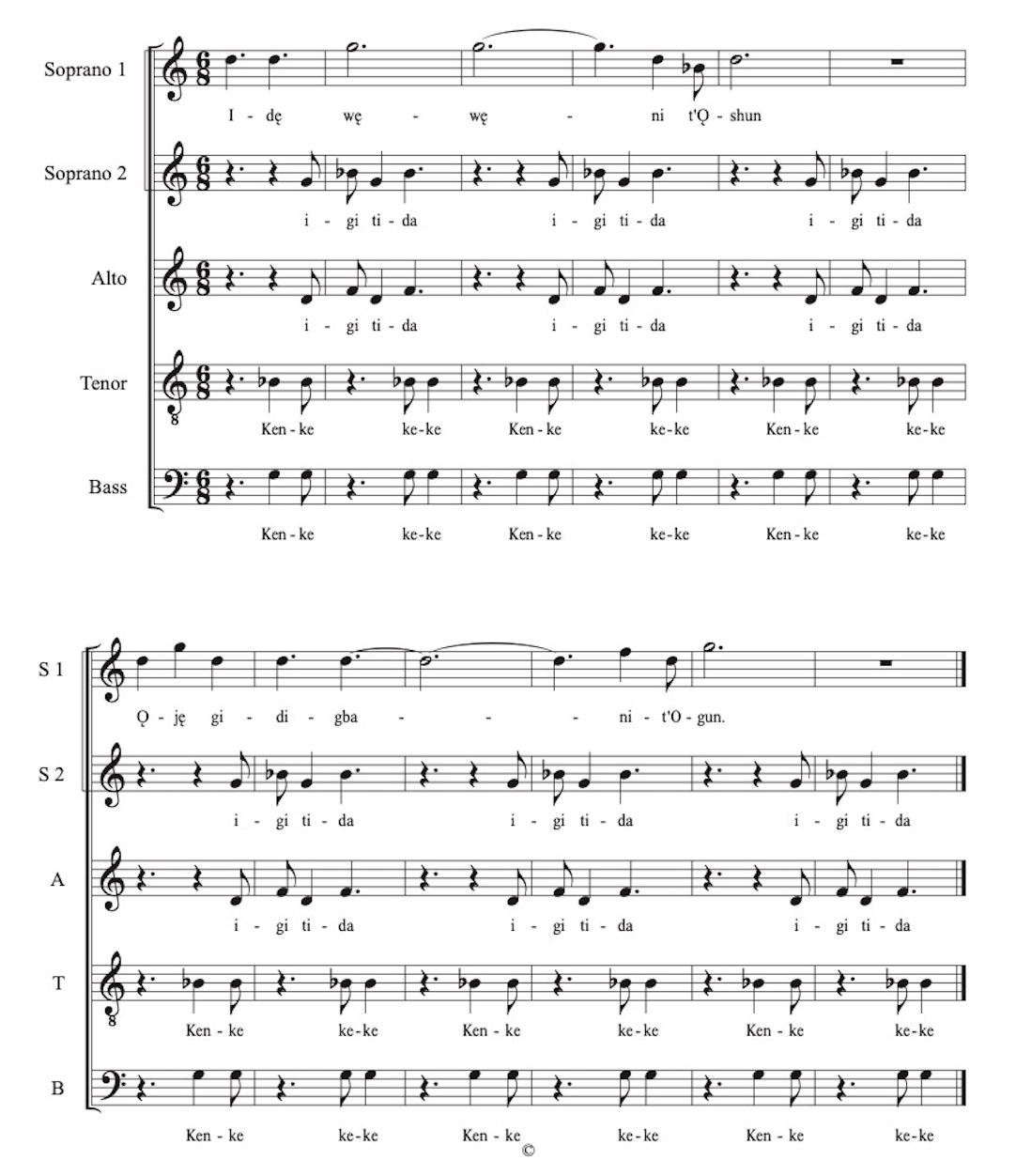

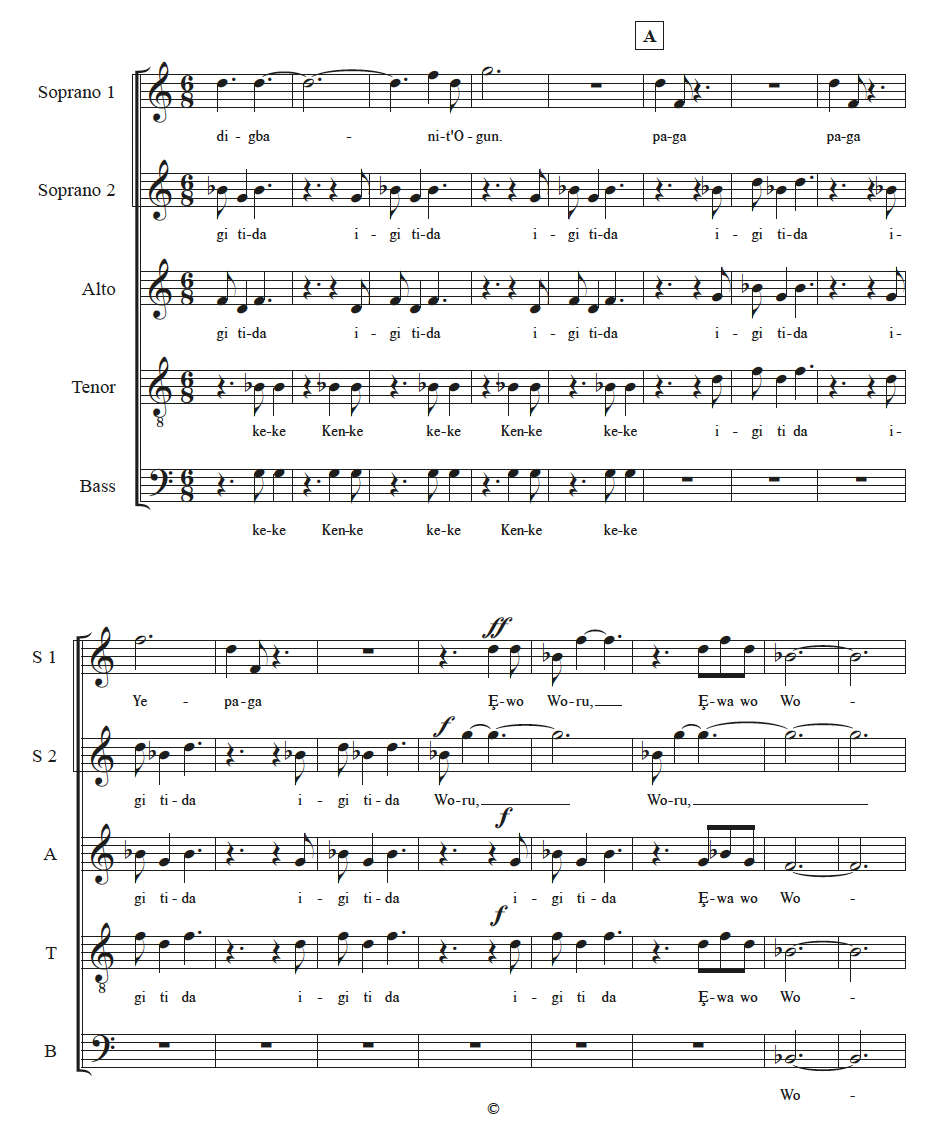

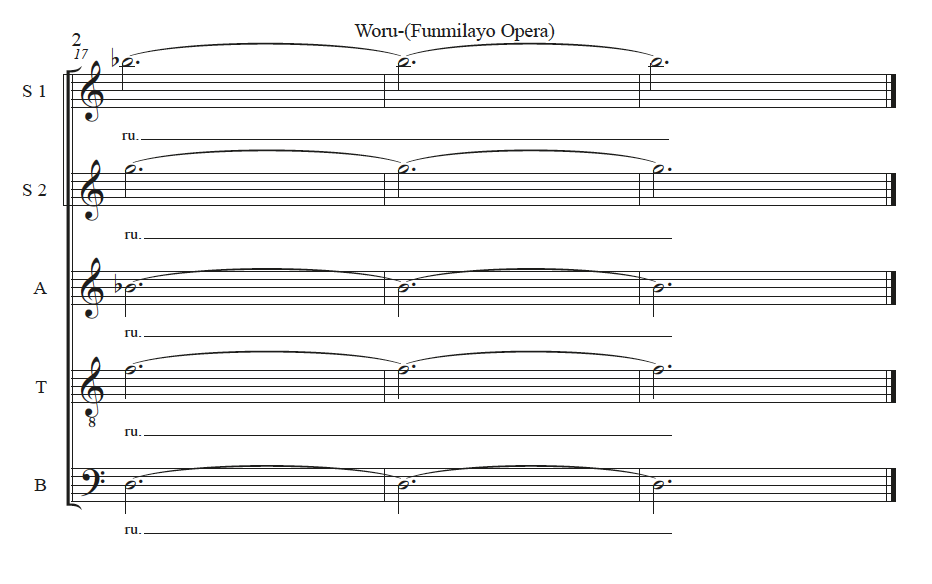

Like Chaka, Funmilayo relies on multicultural musical material, including the use of oríkì as one of the devices for narrating the anti-colonial and feminist activism of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (1900–1978). Kuti, in the 1940s, led the women of Abeokuta in a series of demonstrations against the excessive and anti-woman tax policy of the British and forced the abdication of the Alake (King) of Egbaland, who was seen as a stooge of Britain. The activism of Funmilayo Kuti and the Women’s Union, described by Wole Soyinka as the Great Upheaval, was an epochal event in the nationalist movement leading to Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Funmilayo premiered in the United States in April 2023 as part of the African Opera Series that I started in 2006 at Mount Holyoke and the Five Colleges. It is scored for an intercultural orchestra (featuring African and European instruments), soloists, chorus, and dancers. The music of Funmilayo, like that of Euba’s Chaka, also reflects the experimental and evolving styles of post-colonial African operas within which oríkì chant plays an important role. The opera’s experimental language manifests in the use of varied pitch organisations ranging from tonal, atonal, modal, and dissonant systems.

“Overture to Funmilayo.”

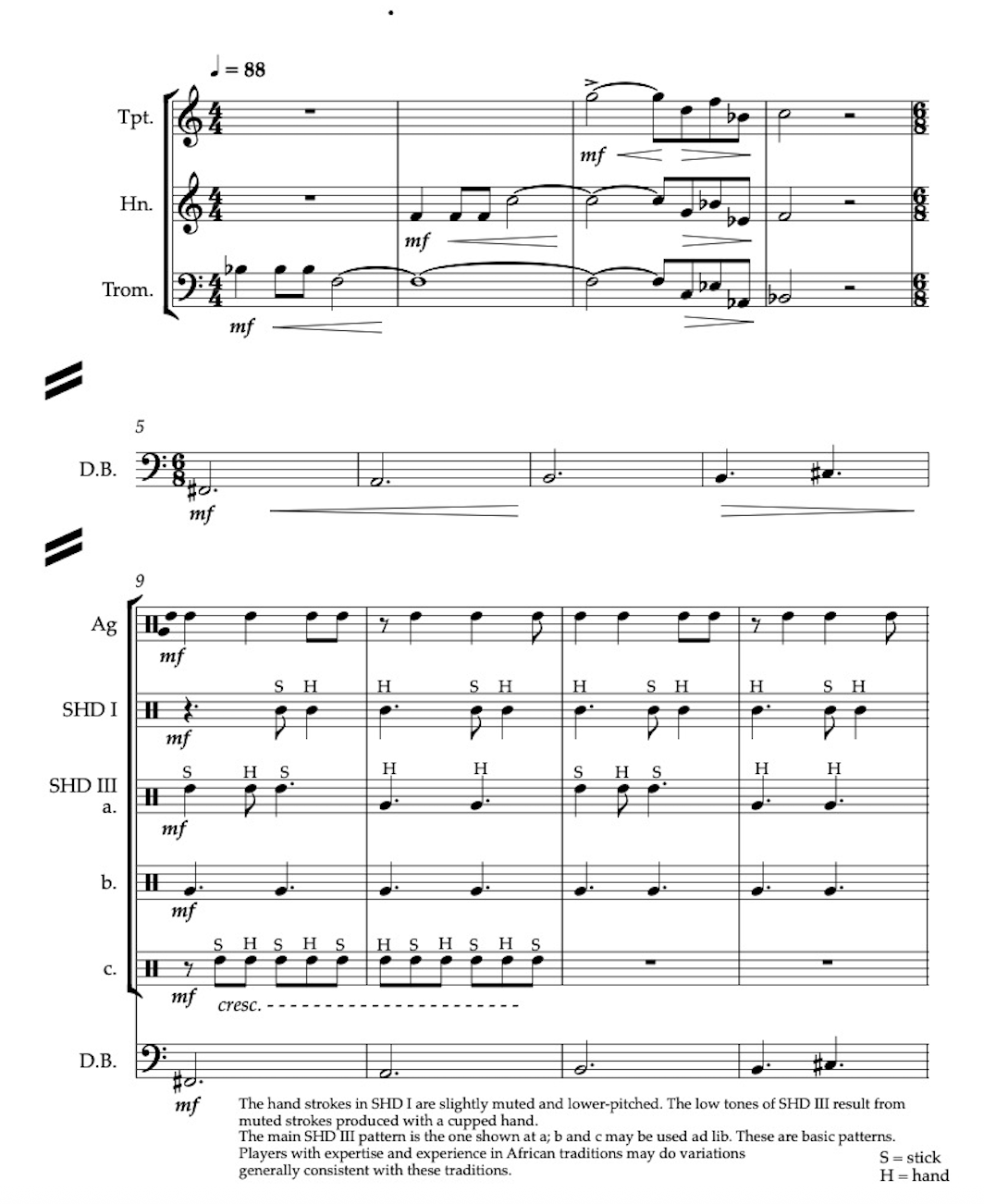

As shown in Table 4, most of the musical pieces follow the Yorùbá-informed episodic structure or variable strophes oriented toward continuous variation. My preference for these forms is to enable narrative fluidity suited to musical storytelling. The episodic form is illustrated in the overture.45 It features diversely sourced cultural and thematic materials suspended over ostinato melo-rhythms and pedals and punctuated with chromatic chords by woodwind and brass. Melodic and choral material are separated by ostinato passages provided by the marimba and Yorùbá dùndún drums. The overture also combines instrumental and vocal passages, deviates into a chant, and features dùndún talking drums in conversation with the symphony orchestra. There is also a chanter, who dances, and whose oríkì narration is accompanied by pentatonic choral harmonies and Yorùbá drums to usher in the royal procession. The arrival of Oba Alade (the king) and his chiefs in full regalia toward the end of the overture demonstrates how shifting sequences of the musical material facilitate and support dramatic actions that advance the plot.

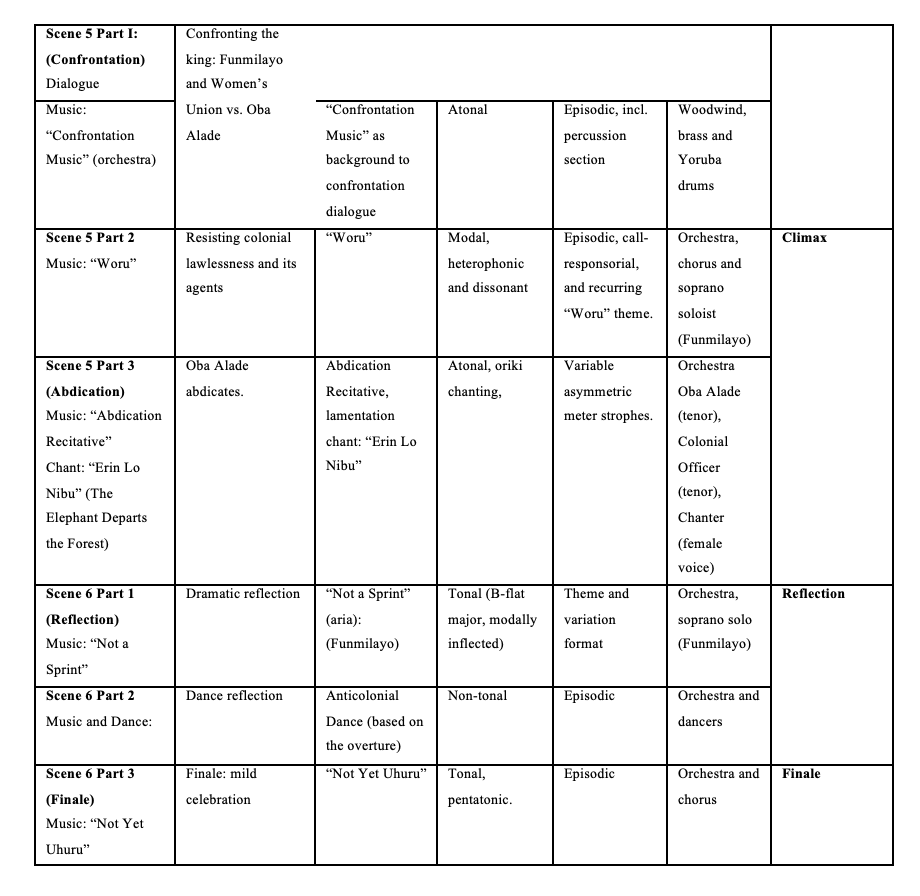

Oríkì serves to introduce the two main protagonists, Oba Alade and Funmilayo (leader of the Market Women). In scenes 1 & 2, it is performed as praise poetry for both characters, describing their heroic deeds as inspired by their ancestors. In the Chant titled “Olufunmilayo, Aya Kuti,” for example, the chanter links the achievement of Funmilayo to those of her ancestors, spotlighting her bravery, power, and nobility.

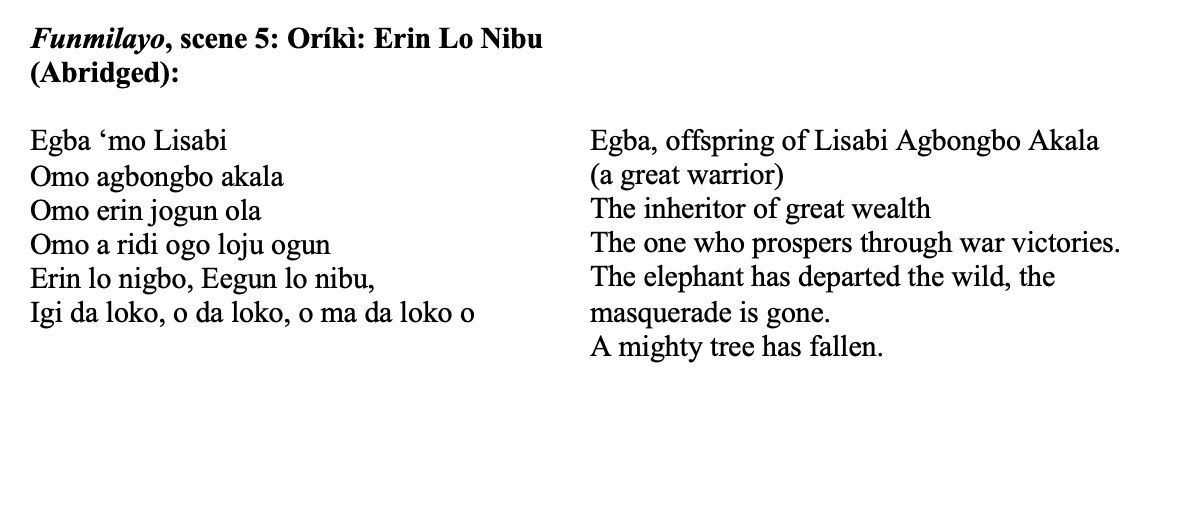

Oríkì is also performed toward the end of the opera as a lamentation, following the abdication of the king. In Scene 5, the oríkì, titled Erin Lo Nibu, combines praise with lamentation to convey a sense of history as decline. The opening part (see translation below) begins with the traditional praise poetry of the King, mentioning the name of a prominent ancestor (Lisabi), describing his wealth, and the war exploits for which the royal family is known. This is followed by the tragic fall of this particular king, who has to abdicate as demanded by the people, an act considered highly disgraceful in Yorùbá culture.

As the two examples show, oríkì is used as a tool of characterization and to historically contextualize the actions of the characters, notably by linking present actions to those of their ancestors. Additionally, oríkì functions as a structural device. As shown in Table 4, it contributes to the expository drama of the opening 2 scenes and helps to consolidate the attainment of the opera’s climax in scene 5.

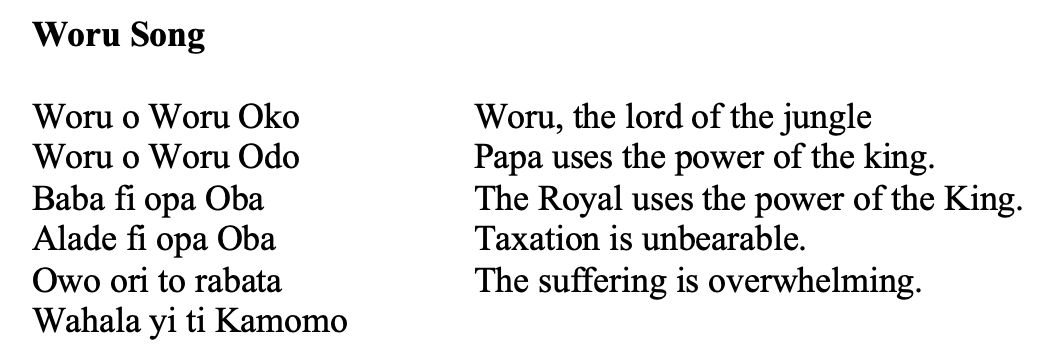

Complementing the use of oríkì is the incorporation of folksongs through paraphrasing or in the harmonic exploration of Yorùbá modal elements. For example, the numbers “Wòrú” (Scene 5, part 2) and “Not a Sprint” (Scene 6, part 3) are based on folk songs, while “Ijoba Geesi” (Scene 2, part 2) simulates Yorùbá folk songs in its modal behaviour as well as melodically and harmonically. The organisation of pitch in the opera is conditioned by a host of factors, for example, to identify a particular character, facilitate dialogue, or accentuate dramatic impetus. This is illustrated in the dramatic climax of Scene 5, part 2, which derives significantly from the tension generated through two different pitch systems. As I explain below, there are two layers to the process: the movement from a modal piece (“Wòrú”) to an atonal one (Abdication Recitative) and the internal unfolding processes in each of the songs, as I explain below, beginning with “Wòrú.”

The dramatic impetus generated in “Wòrú” (for soprano solo and chorus) derives from modal polyphonic procedures, elements of which include overlapping call-and-response phrases, parallel harmonies, pedal, ostinato patterns, and dissonant chords used within the framework of a 4-note modal pitch collection (B-flat, D, F, G) functioning as a subset of a pentatonic scale. Funmilayo’s fury is in the opening measures anticipated by the ostinato patterns of bassoons, cello, and double bass, complemented by the shrilling trills of the oboe. The ostinato material is echoed later and used as a vocal accompaniment to support her reflection about the unruly behaviour of the agents of British colonial rule. Her singing receives support from a dissonant choral pedal point (over which it is suspended) as well as orchestral and choral interjections. Declamation in her part also derives from a relatively expansive register, vagrant phraseology, and continuous exchanges with the chorus. The chorus on its part alternates and layers pedal and melo-rhythmic elements as accompaniment devices, for example, in measures 146–157, Figure 6. It also interjects a passage rendered in parallel harmonies in support of Funmilayo’s attack on the agents of British colonial rule as shown in the text below.

The climax of the song in the closing measures relies on the increased density of modal material, polyphonically generated (mm.153–171, Figure 7)

The dramatic impetus generated in “Wòrú” reaches full climax in the “Abdication Recitative” (a duet, two tenors). The fall of Oba Alade, resulting from the pressure mounted by Funmilayo and the Market Women, is articulated through atonality. The dramatic impact of atonality derives significantly from its appearance immediately after a modal song and is aided by an asymmetric meter (5/4). Significant tension also emanates from the conflicting relationship between the relatively diatonic character of the vocal parts and the atonal orientation of the orchestra (see Figure 8, mm. 1–10). The song proceeds in strophes, beginning with Oba Alade’s expression of frustration, followed by an appeal by the District Officer, an agent of the colonial ruler, urging him not to leave. The self-proclamation of abdication by the king is met with sadness among his supporters as expressed in the Lamentation Chant, the rhythms of Yorùbá dùndún drums, and the melancholy recall of the opening motif by a solo cello (beginning from mm. 103, not shown in Figure 8, but can be watched in the YouTube performance link provided below.).

Abdication Song

I have demonstrated the use of oríkì as a crucial means of linking new operatic forms with precolonial practices. As the discussion reveals, Yorùbá composers from the colonial and post-colonial eras often utilise oríkì in varying operatic contexts and as necessary for specific works. Its application is more pronounced in neo-traditional operas as exemplified by Ogunde’s Yorùbá Ronú. For example, while in the operas of Euba and Omojola, oríkì chant functions within operatic forms influenced significantly by Western styles, in Yorùbá Ronú, it is employed alongside a predominantly Yorùbá-derived song tradition, in which Western tonality plays only a minor role. These stylistic distinctions reflect the unique experiences and individual choices of composers and how they interact with the broader social and historical issues of their times. Oríkì, as a historical, biographical, and panegyric text, evokes meanings that extend beyond the immediacy of specific performance contexts, recalling ancient memories and the heroic deeds of historical figures to illuminate the personalities or enhance the narratives of the actors in the new operas discussed in the essay. The multilayered, multi-sensory, and multi-semiotic features of oríkì resonate productively with the multimedia character and interrogative power of opera. All three categories (Agbégijó, neo-traditional, and “art music”) represent alternatives to a Eurocentric concept of opera because of the significant impact of Yorùbá traditions. The three Yorùbá operas also highlight the political dimensions of operatic performances since the pre-colonial era, ranging from affirming political institutions in Agbégijó to dissecting political power struggles in Yorùbá Ronú, and engaging with the dynamics of colonial power in Chaka and Funmilayo.

At the essay's outset, I underscored the importance of interculturality as a re-signifying perspective with political significance against the backdrop of colonialism. In an essay titled “Musical Narratology: A Theoretical Outline,” Kramer (1991) draws attention to the political and cultural viewpoints that often drive musical narrativity. Specifically, the essay highlights the ideological functionalities of musical narratology, as a “vehicle for both acculturation and resistance to acculturation,”46—an observation highly relevant to the works of African opera composers of the colonial and post-colonial periods. The neo-traditional form of Ogunde diverges from the British Victorian-era music theatre that inspired it, prioritising indigenous Yorùbá song and oríkì traditions with limited incorporation of Western elements as facilitated by the use of the guitar. The music of more recent composers like Euba and Omojola thrives on an intercultural orchestra, featuring songs in the Yorùbá language and combining vocal styles that juxtapose oríkì and Western recitative singing. Both works, however, incorporate Western-oriented pitch systems—atonal and tonal—as elaborated in my discussion. These stylistic elements coexist with a distinctly anti-colonial theme: one celebrates an anti-colonial military strategist, while the other honours feminist resistance to an oppressive colonial tax policy.

The specific stylistic configurations of Chaka and Funmilayo, in which Western elements play a significant role, particularly in instrumentation and variously in terms of pitch systems, elicit questions about how to evaluate the proclivity of African operatic projects to challenge the “coloniality of knowledge.” Is there, for instance, a disconnect between the Western-impacted intercultural style and the anti-colonial messages of the operas? Should the anticolonial or decolonial effectiveness of new African operas be assessed in terms of an incremental and pragmatic approach as offered within an intercultural musical language, or should African operas instigate a more radical Afro-centric departure from colonial musical heritages? In other words, should new operas by African composers entirely reject Western elements to be considered authentically African? As demonstrated in Chaka and Funmilayo, neither Euba nor I is drawn to a simplistic binary approach. The intercultural aesthetics of the two works, despite the substantial differences marking them, reveal a thematic pragmatism that eschews a utopian perspective on decolonisation.47 As a composer, I have always been drawn to an existentialist approach that jettisons a simplistic rejection of Westernisation, while allowing the reality of my bi-musical experience to shape the conception and implementation of my creative work. It is safe to make the same assertion regarding Akin Euba’s approach, given the significant impact of interculturality on his opera. The dynamics of acculturation and resistance, and the tension that defines their relationship as projected in Chaka and Funmilayo, speak to the contingent nature of postcolonial selfhood. They are reflective of the entangled cultural experiences that animate the creativity of post-colonial subjects.48

Abbate, Caroline and Parker, Roger. A History of Opera. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company, 2015.

Adedeji, Joel. “The Origin and Form of the Yoruba Masque Theatre.” Cahiers d’Études Africaines 12, no. 46 (1972): 254–276, https://doi.org/10.3406/cea.1972.2763.

Adéékó, Adélékè. “Oral Poetry and Hegemony: Yorùbá Oríkì.” Dialectical anthropology 26, no. 3–4 (September 2001): 181–192, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021228008790.

Agawu, Kofi. Music as discourse: Semiotic adventures in romantic music. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Aguoru, Adedoyin. “Retrieving, Translating, and Archiving, Hubert Ogunde’s Aye.” Yorùbá Studies Review 7, no.1 (2022): 1–24, https://doi.org/10.32473/ysr.v7i1.131452.

Amin, Nora. “Aida’s Legacy or De-colonising Music Theatre in Egypt.” In Opera & Music Theatre, edited by Christine Matzke et al. African Theatre 19. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey, 2020, 90–106.

Clarke, Ebun. Hubert Ogunde. The Making of Nigerian Theatre. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Clapperton, Hugh. Journal of a Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa. London: John Murray, 1829.

El‐Ghadban, Y. A. R. A. “Facing the music: Rituals of belonging and recognition in contemporary Western art music.” American Ethnologist 36, no. 1 (2009): 140–60.

Euba, Akin. “Concepts of Neo-African music as manifested in the Yorùbá folk opera.” In The African Diaspora, edited by Ingrid Monson. New York: Routledge, 2018: 207–41.

Euba, Akin. Chaka. An Opera in Two Chants. Unpublished Score.

Euba, Akin. Chaka. An Opera in Two Chants. Based on a poem by Leopold Sedar Senghor. City of Birmingham Touring. Conducted by Simon Halsey. Point Richmond, CA: Music Research Institute, 1998, one compact disc.

Irele, Abiola. “Narrative, History, and the African Imagination.” Narrative 1, no. 2 (May 1993): 156–172.

Irele, Abiola. “Is African Music Possible?” Transition, no. 61 (1993): 56–71, https://doi.org/10.2307/2935222.

Jeyifo, Biodun. The Yorùbá Popular Travelling Theatre of Nigeria. Lagos: Nigeria Magazine, 1984.

Kasule, Samuel. “I Smoke Them Out: Perspectives on the Emergence of Folk Opera or Musical Plays in Uganda.” In Opera and Music Theatre 19 edited by Christine Matzke et. al., Oxford: Boydell & Brewer, 2020: 183–93.

Kramer, Lawrence. “Musical Narratology: A Theoretical Outline.” Indiana Theory Review 12 (1991): 141–162, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24045353.

Lander, Richard. Records of Captain Clapperton's Last Expedition to Africa, vol. 1. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, I830.

Leonard, Lynn. The Growth of Entertainment of Non-African Origin in Lagos. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Ibadan, 1967.

Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham, Bc, and London: Duke University Press, 2018.

Mignolo, Walter. "The Colonial Matrix of Power." In Talking About Global Inequality: Personal Experiences and Historical Perspectives, edited by Christian Olaf Christiansen et all. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023, 39–46.

Nii-Dortey, Moses N. “Historical and Cultural Context of Folk Opera Development in Ghana: Saka Acquaye’s ‘The Lost Fishermen’ in perspective.” Institute of African Studies Research Review 27, no. 2 (2012): 25–58.

Ogunde, Hubert. Yorùbá Ronú (Yorùbá and English Lyrics). Accessed June 1 2025. https://drbiggie.wordpress.com/2013/11/02/Yorùbá -Ronú-Yorùbá -and-english-lyrics-chief-hubert-ogunde/.

Omojola, Bode. Nigerian Art Music: With an Introduction Study of Ghanaian Art Music. Ibadan: Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique-Nigeria, 1995. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.ifra.598.

Omojola, Bode. Studies in African Pianism: A Collection of Seven Original Works for Piano. Bayreuth African Studies 63. Bayreuth: Bayreuth African Studies Breitlinger, 2003.

Omojola, Bode. “Rhythms of the Gods: Music, Spirituality and Social Engagement in Yorùbá Culture.” Journal of Pan African Studies 3, no. 9 (2010): 232–50.

Omojola, Bode. Yorùbá Music in the Twentieth Century. Identity, Agency, and Performance Practice. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2012.

Omojola, Bode. “Towards an African Operatic Voice.” In Opera & Music Theatre, edited by Christine Matzke et al. African Theatre 19. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey, 2020, 107–35.

Bode Omojola, “Overture to Funmilayo,” accessed May 11, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9ZgNUpDIO4.

Osadola, Oluwaseun Samuel and Adeleye, Oluwafunke Adeola. “A Re-assessment of the Exceptional Indigenous Political Setting of the Yorùbás: Historicizing the Formation of Old Oyo Empire.” London Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences 19, no. 6.1 (2019): 27–33.

Gerald, Prince. “Narratology”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature (July 2019). Accessed May 30, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.996.

Soyinka, Wole. “African Traditions at Home in the Opera House.” The New York Times: Arts and Leisure 25 (1999): 25–26.

Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi. Against Decolonisation: Taking African Agency Seriously. London, England: Hurst Publishers, 2022.

Taruskin, Richard. Taruskin, Richard. Review of She Do the Ring in Different Voices, by Carolyn Abbate. Cambridge Opera Journal 4, no. 2 (1992): 187–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/823744. https://doi:10.1017/S0954586700003736.

Yorùbá Ronú Theme Song49 by Hubert Ogunde

(Yorùbá song text and translation)

Mo wo Ile Aye o, aye sa malamala;

Mo ma b’oju w’orun okunkun losu bo’le;

Mo ni eri eyi o, kini sele si Yorùbá omo Alade, kini sele si Yorùbá omo Odua;

Ye, ye, ye, yeye, ye awa mase hun, oro nla nbe;

Yorùbá nse r’awon nitori Owó, Yorùbá jin r’awon l’ese nitori ipò;

Won gbebi f’alare, won gba’re f’elebi;

Won pe olè ko wa ja, won tun pe oloko wa mu;

Ogbon ti won gbon lo gbe won de Ilé Olà, ogbon na lo tun padawa si tunde won mole;

Awon ti won ti n s’Oga lojo to ti pe, tun pada wa d’eni a n f’owo ti s’eyin.

Yo, yo, yo, Yorùbá yo yo yo bi ina ale; Yorùbá ru ru ru bi Omi Òkun; Yorùbá baba nse…Yo yo Yorùbá Ronú o!

Yorùbá so’ra won di boolu f’araye gba;

To n ba gba won soke, won a tun gba’won s’isale o;

Eya ti o ti kere te le ni won ge kuru;

Awon ti ale f’ejo sun, ti di eni ati jo;

Yorùbá joko sile regede, won fi owo l’owo;

Bi Agutan ti Abore n bo orisa re o!

Yo yo Yorùbá r’onu o!

Ori ki ma i buru titi, ko bu ogun odun;

Leyin okunkun biribiri, Imole a tan;

Ejeka pe Olodumare, ka pe Oba lu Aye; k’ayewa le dun ni igbehin, igbein lalayo;

Ile mo pe o, Ile dakun gbawa o, Ile o;

Ile ogere, a f’okó yeri…ile!

Alapo Ìkà, o te rere ka ibi…ile!

Ogba ragada bi eni yeye mi omo adaru pale Oge…Ile, dakun gba wa o…Ile!

Ibi ti n pa Ika l’enu mo…ile!

Aate i ka, o ko ti a pe Ile…Ile!

Ogbamu, gbamu oju Eledumare ko mase gbamu lowo aye…Ile…dakungba wa o…Ile

Ehen, ehen awa gbe ori ile yi pe o;

Eni ba dale, a ba ile lo…peregede o…ehen ehen awa gbe ori ile yi pe o;

Oduduwa bawa tun ile yi se o…to’wo, t’omo o…ehen…awa gbe ori ile yi pe o;

Oduduwa da wa l’are o, kaa si maa r’ere je o…ehen awa gbe ori ile yi pe o!

Yo yo yo Yorùbá Ronú o!

English Translation

I look down upon the Earth and it looks faded and jaded;

I look up to the skies and see darkness descending;

Oh! What a great pity!

What has become of the Yorùbá?

What has befallen the children Odua?

Hey, hey hey hey, hey hey…

We appear helpless and the situation ominous;

The Yorùbá inflict rain on themselves for the sake of wealth;

The Yorùbá undermine one another in pursuit of position;

They declare the innocent guilty and the guilty innocent;

They induce thieves to invade a farm and invite the farmers to apprehend them;

The same cleverness that was responsible for their past successes;

Has now turned out to be their albatross;

Impactful leaders of the past have now been rendered irrelevant;

Yo, yo, yo Yorùbá yo, yo, bright as light on a dark night;

Yorùbá ru, ru, ru as the rumblings of the Sea;

Yorùbá baba deserves to be baba;

Yo, yo, yo.Yorùbá reflect.

The Yorùbá have turned themselves into a football for the world to kick about;

They are lobbed up into the sky and trapped down to the Earth;

A region that was already small, has its size further reduced;

And those through whom we could have sought redress;

Have been rendered men of yester years;

Yet the Yorùbá sits down helpless, like a sacrificial lamb;

Yo, yo, yo, Yorùbá reflect;

But misfortune, I say, does not last for a lifetime;

For after darkness comes light;

So let us cry unto Edumare, the makers of heaven and earth to grant us recovery;

For he who last, laughs best;

Oh mother earth! I call upon you;

Mother Earth, oh! Mother earth;

Please come to our aid, Mother Earth;

Slippery earth, whose head is shaved with a hard worker’s Hoe;

Whose wicked container spread out to contain evil;

Flung out as a mat, in the manner of my mother, scion of those who spread ash to heal the earth;

Mother earth, please come to our aid, Mother Earth!

Fame that confounds the wicked… Mother Earth, please come to our aid, Mother Earth;

Spread out and cannot be folded…Mother earth, please come to our aid, Mother Earth!

The sheer expanse of Edumare’s view cannot be contained within human arms…oh mother earth, come to our aid!

Yes, yes, yes, yes, so we may live long on this earth;

Those who renege on oath will pay the price, yes yes yes, so we may live long;

Oduduwa, please aid us to replenish the earth for our success and fecundity…yes, yes, so we may live long on this earth;

Oduduwa vindicate us so that we can succeed; yes, yes, yes, so we may live long on this earth.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.