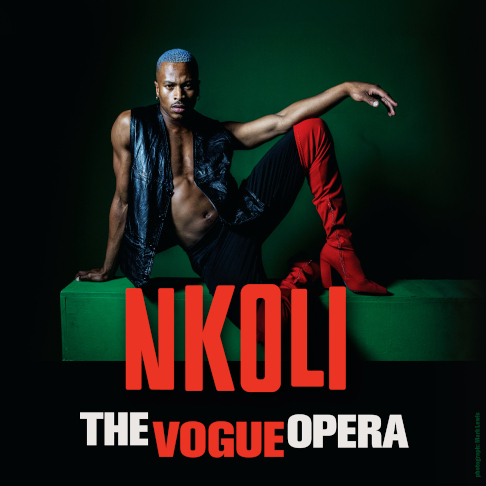

This interview is based on the author’s discussions with the creators and production team of the 2023 South African production Nkoli: The Vogue Opera. It sets Nkoli within the context of a brief, selective historical account of other South African opera initiatives challenging, in various ways, the imported conventions of “grand opera”.1 It discusses the choice of the “vogue opera” form, and through its creators’ reflections, how they define the production’s decolonising features: an activist intention; a collective process of creation; a non-conventional staging; the use of diverse musical sources; and, most importantly, the subversion of both gender and heroic character binaries.

This interview-based contribution seeks to explore the different ways in which the makers of the production Nkoli: the Vogue Opera (which dramatises the life of an important Black, gay activist in South Africa’s struggle against apartheid) frame their work as challenging the kind of opera that arrived with colonialism, and what they see as the defining elements of decoloniality in that context.2 The starting point for my own work as a music writer and researcher, concurring with Eric Porter, is that we must hear how the makers of cultural texts such as music theorise their own creativity: that a democratic, decolonial musicology must embody “more than the ideas of critics and traditional intellectuals”, significant though those are. It is not my project here to measure Nkoli against any externally constructed decoloniality yardstick from either scholars or critics.3

I interviewed the Nkoli ensemble for journalistic purposes.4 But their generous conversations gave me greater breadth and nuance than my commissioned 1,000 words for The Conversation Africa could contain. Often couched in expressive and experiential rather than musicological terms, a clear discourse emerged about the work they were creating.

Composer, dramaturge, librettist and others asserted four key features of Nkoli. It uncovers hidden history with an explicit activist intention. A multivocal, collective development and production process counterbalances any risks of merely appropriating the vogue form. The score draws musical inspiration from diverse African and diasporic sonic sources. Finally, both narrative and staging subvert the gender and heroic character binaries associated with what my interviewees variously termed “grand” or “conventional opera-house” or “mainstream” or “Eurocentric” or just “that kind of” opera.5

As contextual framing for these conversations, I include a brief historical sketch of Eurocentric opera in South Africa and how it served the colonial project, and provide illustrative examples of other local productions positioning themselves as opera, challenging this model in different ways. Nkoli is the first to create a “vogue opera” form, adding an innovative, specifically Black queer, dimension that locates the work as resistance at the point where the national, cultural and gender identity oppressions enacted by colonialism intersect.

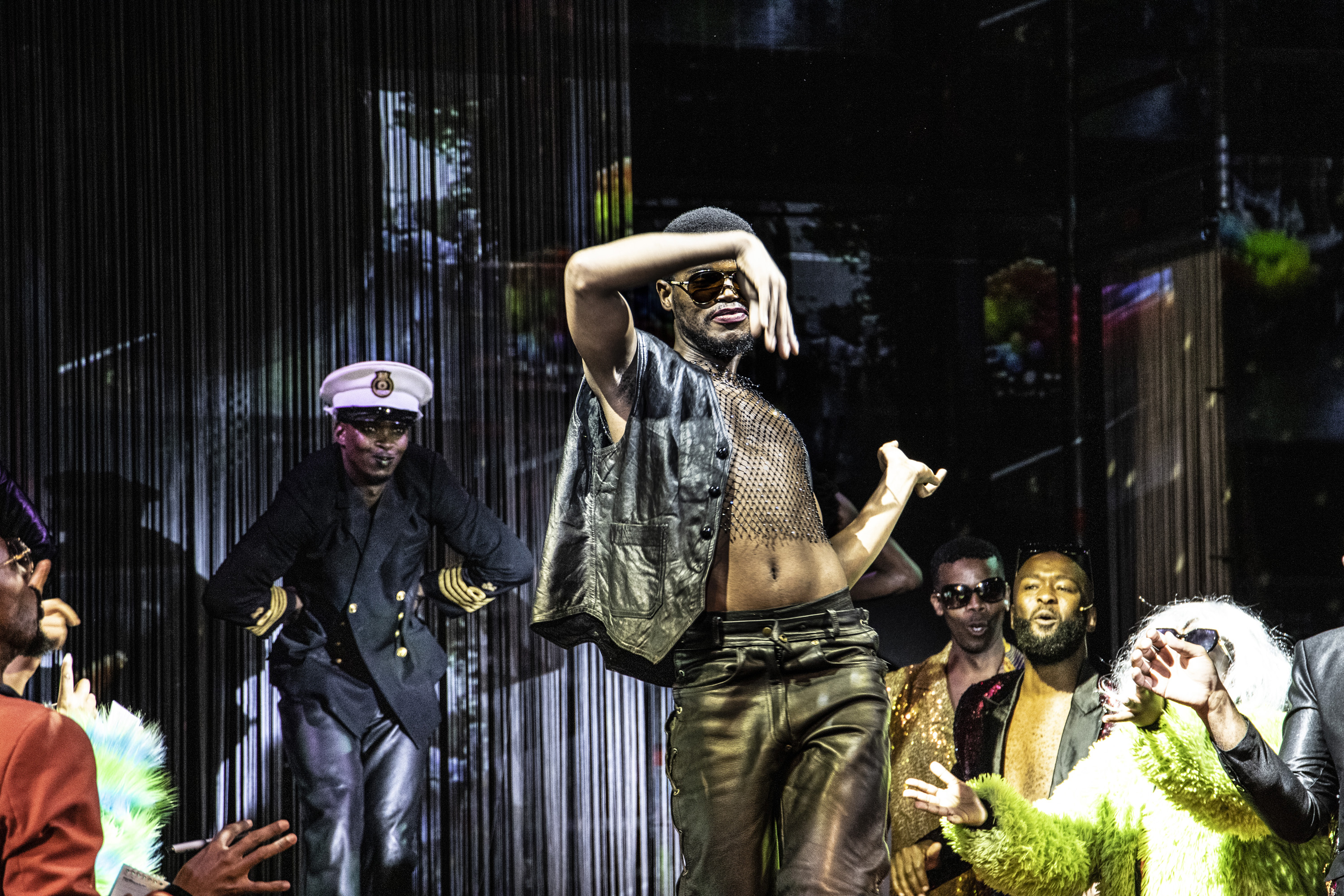

Amid the industrious chaos of a still only part-dressed auditorium in Johannesburg’s Market Theatre in late 2023, the soundcheck for Nkoli: the Vogue Opera begins. Nobody’s singing from the actual score at this point. Instead, individual try-out fragments come from a patchwork of genres: baroque counter-tenor embellishments; the choral hymn “Amazing Grace”; “Vedrai, carino” from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni, the Queen of the Night’s aria from his Magic Flute. Briefly, soprano Anne Masina reduces the bustle to stunned silence with the power and purity of her notes. Composer Philip Miller6 sits behind his laptop, cueing up passages that still need work. Opera people are in the house, no doubt... But, a “vogue opera”?

“Vogueing was a tool of the Black queer revolution in the US,” reflects Miller. “In its defiance of straight sensibilities, in its challenges to the hyperman, and its assertion of the right to joy and the possibility to be anyone you want to be.”7

Vogueing (ballroom culture) emerged as a form of stylised solidarity and defiance for working class African-American and Latinx queer communities during the 1980s: community events where contestants walk a runway as characters riffing on stage and screen superstars and the imagery of high-fashion magazines. Its roots can be traced back to the Harlem drag balls of the Nineteenth Century.8 Vogueing initially found a wider audience through Madonna’s 1990 music video, Vogue,9 film-maker Jennie Livingston’s documentary of the same year, Paris is Burning, and, more recently, in television shows such as Ru Paul’s Drag Race and as an element in Beyonce’s 2023 Renaissance tour.

“But vogueing,” says Miller, “is also not so distant from the story of Simon Nkoli, who, as part of his revolutionary activism, was a patron of beauty pageants asserting gay identity, including Miss Gay Soweto, in the 1990s (...) and who loved disco music.”10 That was part of the conceptual fit Miller saw when he was developing a form for Nkoli. He wanted to foreground the story of Nkoli – neglected in South African liberation movement history, but pivotal in the struggles around sexuality, gender identity and gender rights that ultimately saw South Africa’s post-liberation Constitution outlawing discrimination based on sexual identity, sex or gender.11

The production’s dramaturge, Londoner Rikki Beadle-Blair12, who hosts vogueing balls in the UK, recalls seeing “a lot of opera [there], but never thought it was my lane,” but was “blown away and captivated – yes! – by the idea of a vogue opera and snatched the gift from Philip’s hand.”13

And vogue opera remains opera, says Miller. It employs “the form and sensibility of ‘grand opera’ to bring into focus an aspect of Simon [Nkoli]’s personality, who himself embraced the spirit of exaggerated drama, which is noticeable both in his letter-writing and his love for the ‘popstar diva’”.14

Miller also sought to speak to younger audiences “most of whom wouldn’t dream of going to something called an opera”,15 and in which process as well as product could defy the exclusionary history of the genre. Despite the emergence of Black soloists and initiatives to “Africanise” (through changes to setting, costume and language of established repertoire16), opera institutions in South Africa face shrinking resources and falling audiences.17 Miller notes that the genre remains “rightly or wrongly, perceived as elitist”,18 something he sees reinforced by high ticket prices, and possibly influenced by seasons dominated by performances of Nineteenth Century European “grand opera favourites”.

Back in 1959, composer and co-librettist Todd Matshikiza steadfastly insisted that his work, King Kong, was an “all-African jazz opera”, as the South African long-playing album cover declared.19 Yet from its inception, patrons, promoters and critics alike referred to it as a “musical”, and by the time it reached London in 1961, that was what the posters called it too.20

That categorical elision was not mere marketing. Contested genre definitions around both “jazz/African-American music” and “opera” had featured in critical writing at least since the opening of George Gershwin’s one-act Blue Monday in 1922, often masking what were actually discussions about race, class, dominance and ownership.21 In South Africa, as in the rest of the colonised world, opera had historically functioned as both a transcendent musical experience for some, but also as an instrument and enaction of control over knowledge and representation. 22

The significance of European-originated opera in South Africa outweighs its relatively small performance and audience footprint: first, for the British colonial project and even more for displaying Afrikaner cultural dominance under apartheid. The genre has undergone multiple forms of “indigenisation” since the colonial era.23 But King Kong has much in common with Nkoli in in how both employ urban, syncretic popular music to assert the right to cultural space of a community erased from hegemonic discourses. At the time of King Kong, Black majority culture was narrowly exoticised as rural, unchanging and tribal and the Black city was under forced removal; a sophisticated Black urban presence was being rendered officially invisible.24 During the period of Nkoli’s activism, nonconforming sexual orientations were vilified, stereotyped and silenced, as sin by established Christianity and as an irrelevant embarrassment in liberation movement discourse, as the Nkoli production documents.

At the same time, opera establishments in colonised nations continued implicitly (through access and affordability) and explicitly (through colour bars at every level) to police who could create and perform opera, and who could attend its performances, barricading off physical and cultural space for white settlers and their kin. Indigenous cultures (including those less wedded to gender binaries) were erased as products of a primitive “Other”. Said, reflecting on the imperial Cairo Opera House, foregrounds the function of “managing and even producing [the Orient]” reflecting subaltern Others back through the eyes of the colonisers and thus reinforcing imperial hegemony.25 In this world of stark binaries, operatic performances enshrining the values—production and ideological—of the imperial metropolis reassured nostalgic settlers about the enduring link with “home”.26

In South Africa, music education in Black schools was diminished and eventually almost eliminated under apartheid; Black choral composers and performers were limited to tonic sol-fa notation, and Matshikiza, for example, was never able to access the full concert orchestra he sometimes composed for (Makhaliphile; Uxolo).27

Though there is a “paucity” of musicological studies of European operas in South Africa, because of its small niche,28 Hilde Roos observes “similar patterns” of opera development between South Africa and other “white colonies”.29 Formal opera productions arrived later, but melodies from operatic scores were heard at recitals in the homes of early settlers, at the balls of colonial grandees and in the repertoires of army marching bands. Subsequently, touring European opera companies served as missionaries for the colonial cultural gospel, and later still private opera houses and theatres were built in big cities. Operatic training became part of white music education and local white performers and impresarios grew in prominence in South Africa, at the very time their Black counterparts were being pushed out of music-school classrooms and off stages by apartheid.30

But where there is repression, there is resistance. Some was intentionally political defiance of racist laws; some, simply the assertion by South Africans of colour of their right to create, perform and enjoy any genre. In the early years of apartheid, when “ethnicity [was being] sonically mapped out”, vaudeville performers (such as Griffiths Motsieloa, leader of “De Pitch Black Follies”), would introduce renditions of operatic arias, alongside soliloquies from Shakespeare, into the “concert” segment of Concert and Dance shows.31 The EOAN Group established in Cape Town’s District Six in 1933, was, by the late 1950s, home to “the first amateur company composed of coloured people who learnt to sing in the Italian style and perform world known operas”.32 The company was moved out of the city under the racial zoning clearances of the mid-1960s. EOAN graduates included tenor Joseph Gabriels, who went on to sing professionally at the New York Metropolitan Opera – but never in any of the white-controlled South African State Theatres where operas were staged.33

Natal-based contralto Patti Nokwe sang spirituals, gospel songs and operatic arias and won multiple music contests in her home province in the 1950s and 1960s. But when she sent tapes of her singing to the South African Broadcasting Corporation’s Radio Bantu to secure an engagement, they were rejected by controller Yvonne Huskisson “who declared that ‘she sang too much like white people’.”34

One dedicated fan of Italian opera was poet and sometime 1950s Sophiatown gangster Don Mattera. His grandfather was Italian, and he loved the music, but was met with downright incredulity when, as a “native”, he tried to attend:

We went to recitals too. We went to the City Hall. We used to sit in the corner while the whites would occupy the best seats. And we listened to the likes of Beniamino Gigli: great singers of classical music. (...) I remember one time I phoned to book some tickets (...) and this woman asked me where I would like to sit. I said “in the corner on the left hand side facing the stage”. And she said: “But that’s where the Black people sit” – except she didn’t say “Black people”, she said “natives”. Well, I’m Black, but I never said I was a “native”. And she said “What? But you sound white!”35

These few illustrative instances from many, sketch an era when exclusion was pervasive. For this reason, Matshikiza’s declaration of King Kong as a “jazz opera” signified far more than genre. As well as the right of Black composers and performers to create opera, the King Kong score asserted the place of Black music idioms within the genre and interrogated conventions around who could be protagonists, what was an appropriate context and what audiences the form addressed. The narrative employed an African storytelling frame: Matshikiza’s original washerwomen chorus invoked a tradition in which senior women are the historic custodians of tales. The musical and theatrical idioms were gradually diluted during rewrites, and further during the show’s 1961 London and 2017 Cape Town runs.36

Up to the 1960s, “opera” on the white theatrical landscape had a small footprint, despite porous definitions admitting light operetta and Afrikaans-language folk drama, and organisational and financial support from the state-run National Theatre Organisation after 1947.37 But after 1963, for reasons inextricably linked to the consolidation and promotion of apartheid, resourcing for the genre grew, mirroring its perceived symbolic importance. In 1962, the National Party Government dissolved the National Theatre Organisation, created four provincial Performing Arts Councils (PACs) with wide powers, and made provision for the construction of 48 new theatres (in white areas). Broad programming was sidelined in favour of “high” forms such as opera and ballet, nurturing Afrikaans translations of serious European works and new works rooted in that language and tradition.38

Like many structures created by the regime, this was a way of expanding white employment, here in cultural entities. It also advanced “the agenda of the Afrikaner nation,” portraying the volk [the white Afrikaans-speaking population] as possessing sophisticated European roots and at the same time dynamically “indigenising European art forms” intended as a persuasive demonstration that the apartheid nation was “civilised”.39

Opera was henceforth generously funded and foregrounded. In each of the four keystone Performing Arts Council theatres, the largest and best-equipped performance space was named the “Opera Theatre”. When the Johannesburg Civic Theatre, also a child of the PACs and built at a cost of R720 000 (US $514,712), opened in 1962, impresario Percy Tucker notes it was welcomed as “especially valuable to the enhancement of ballets and operas,” opening with a season of three operas.40

The first official PACT season in 1963 included runs of Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca (1900) and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (1786) in Afrikaans. The 1964 Johannesburg Festival featured Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore (1853). When CAPAB’s Nico Malan Theatre opened in 1971, it raised the curtain on Verdi’s Aida (1871). When the Civic celebrated its 20th anniversary in 1982, it did so with, among others, Puccini’s Turandot (1926).41

Even into the early post-apartheid years this largesse continued. When the Civic closed for renovations in 1987, one priority was facilitating the transfer to Johannesburg of PACT operas staged at the State Theatre in Pretoria.42 Tucker estimates the final cost (after multiple overruns) at R132 million.43 The result was “one of the most technically sophisticated theatres in the southern hemisphere, with facilities including six stage wagons, one of which provided the outer and inner revolves that accommodating State Theatre opera and other productions required.”44

By the time the Civic reopened in 1992, apartheid was at an end, cultural institutions were being renamed and arts councils reconstituted. Fears about the future of opera among the white minority were initially reflected in “a survivalist approach in arts reportage that highlighted a political attack on a Western art form”.45 Dr Ben Ngubane, the first post-apartheid Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology in the ANC government, meanwhile, framed arts decolonisation in terms of product rather than process or discourse: “If there is a need to perform Romeo and Juliet in Zulu, the [new] Arts Councils should make it happen.”46

The remaining formal barriers to learning, creating, performing and appreciating opera – many of which had, in any case, been wound down during the regime’s final decade – officially fell away. By the early 2000s, songs from “grand opera” were being prescribed as choral competition set works, the community context where South Africans excluded by apartheid historically acquired formal vocal skills.47 But stereotypes (musical or societal) did not instantly dissipate, nor did gatekeeping end. Issues of affordability persisted. Matshikiza’s deliberate interrogation in the 1950s of who could be a hero, and of the sonic and staging idioms employed in telling their story, remained intensely relevant.

Subsequent compositions certainly took those questions seriously. For example, Professor Mzilikazi Khumalo’s 2002 opera, Princess Magogo ka Dinizulu posed (as his 1982 oratorio, Ushaka, had also done) a nationalist challenge to Western operatic convention in deploying melodic, harmonic and rhythmic elements of isiZulu musical tradition and using the isiZulu language.48 Its protagonist was nevertheless a princess, and the gender roles, narrative treatment and heroic staging her story received would not have been unfamiliar to a “grand opera” audience.

Bongani Ndodadana-Breen’s 2011 Winnie, the Opera was sung in English and isiXhosa, and also wove African musical idioms into a score much more modernist than Khumalo’s. Ndodana-Breen described the work as: “the first full-length opera to be written and orchestrated by an African. I do not orchestrate the European way...it is sparse. I use African sounds, the brass band, the church, the village...we adopted things from a traditional context.”49 But the work’s protagonist, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, was also certainly a “princess” (of the liberation movement, as well as having been born into Xhosa aristocracy) and, said the composer, “a tragic heroine and that is why she is the perfect subject for an opera.”50

Constructions of gender and sexuality were central to how the protagonists in grand opera were represented. As part of colonial cultural hegemony, the presentation of gendered stage stereotypes had run parallel to the legislated gendering of social roles and relationships, patriarchal restrictions on female autonomy, and “anti-sodomy” legislation based on Roman-Dutch law. The genre’s dominant tropes foreground triumphalist depictions of imperial conquest and hyper-masculine conquerors (sometimes actual colonisers such as Vasco da Gama; see Andrews, 2007) defeating treacherous male protagonists or raping (perhaps euphemised as marrying) doomed, often passive, barbarian princesses.

That did not change substantially even in operas challenging triumphalist colonial narratives. King Kong’s hero was a perpetrator of gender-based violence, and its heroine a glamourised victim of it.51 Even when nationalist and liberation heroes walked some stages, and African and popular music genres sounded there, queer protagonists and culture did not. Binary gender roles remained unquestioned.

Nkoli surfaces those questions. At a time when the LGBTQI+ community is often stigmatised—inaccurately and a-historically—as un-African, Simon Nkoli’s liberation role and queerness go unmentioned in post-apartheid school curricula.52 Actor Bongani Khubeka, who plays Nkoli’s prison ally among the Delmas triallists, Gcina Malindi, says he “didn’t even know there was a queer activist in the struggle.”53

Miller, who knew Nkoli and remembers him warmly, wanted to put the story of that life back into the historical record: “He hasn’t been celebrated as other struggle figures have. His life of intersectional activism from as early as the 1980s is inspirational (...) at a time when homophobia and transphobia are rising everywhere, even in South Africa.”54

Miller did not set out to compose a hagiography centred on one, larger-than-life, perfect protagonist. Nkoli had blind spots. Miller recounts conversations with Nkoli’s mother Elizabeth that exposed how, while he was being feted worldwide post-apartheid, she still lived in her tiny township home, dependent on a social grant.55 In the documentary Simon and I, Beverley Ditsie is frank about Nkoli’s dismissal, almost to the point of misogyny, of the concerns of the lesbian community.56 (Both Miller and Ditsie recall how, later, he accepted that his own earlier disdain for lesbian struggles had precisely the same colonial/apartheid roots as the regime’s suppression of Black and male gay rights.)57

For Miller’s co-lyricist, rapper S’bo Gyre, the opera’s critique of that is “the real revolutionary shake-up: one of the strongest decolonial moments. Nobody who’s even a little familiar with vogueing is going to be shocked by an MC with a dildo on their head. But that moment will shock them – and make them think. You see Simon Nkoli’s narcissism, his disregard for others – whoa! Is this a hero? And yet he also definitely was a hero...”58

Gyre, born in Kwazulu-Natal but educated in Johannesburg, had been destined for a career in law. Singing was a hobby, and while studying for his law degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2015, he began rapping “as a way to improve my singing, particularly breathing.”59 His first album, the 2018 Queernomics, scored considerable success; his second, the 2024 Altar Call, he says, “would never have existed without my work on Nkoli: it gave me room to take more risks.”60

Mutual friends had networked Miller and Gyre; a period of online exchange of beats and proposed lyrics—“a bit hit-and-miss”—culminated in live studio collaboration to fit score and words together and develop both.61

Presenting the ambiguities of Nkoli’s character, Gyre suggests, is where the vogue form, with its assertion of fluid space and rejection of rigid categories, is uniquely able to embody the narrative in ways more conventional operatic narrative might not.62

Such conventional operatic telling, reflects Miller, as well as the historic imaging of struggle, would naturalise anti-apartheid resistance “as the territory of the strong male activist (...) and we tend to create our great heroes in binaries: saint or sinner.” That was not, he recalls, the biography that emerged from consultation and debates within the cast and with Nkoli’s circle: “You need to capture the full human being: the flaws and the fabulousness of Simon; his fierce activism and leadership – but also his vulnerability”.63

How the production treats the end of Nkoli’s life illustrates the work’s decisive break from “grand opera” stereotypes. The tragedy of losing such a figure so young (and from a condition the audience well knows is now treatable) is acknowledged. There’s a pause for grief. But this is not La Bohème, where the tragic heroine expires of consumption with her lover clasping her tiny, frozen hand. This is not the kind of production where the curtain falls on Rodolfo, silently bowed over Mimi’s deathbed.

Rather, the opera ends with Nkoli’s funeral: family, community and comrades together; struggle songs; a braid of African music styles, traditional and modern; and the upliftment and hope offered by collective remembering and collective action. For Gyre, how the drama and the music handled that moment was pivotal for the message of the whole production: “It’s an archival work and a didactic work too. It needs the emotions [of that scene] to start heavy. It’s like you have a billion doves trapped in a cage—and then they need release; they need to fly!”64

Liminal tensions characterise the music of Nkoli too. Miller’s score employs contemporary concert music alongside and intertwined with elements of choral protest song (“which is already often magnificently operatic,” says Miller) and 1980s South African pop and international disco. “Through Simon’s [prison] letters,” the composer says, “I had magnificent access to his playlists.” Nkoli was a romantic. Together with pop hits by South African artists such as Brenda Fassie and Hotline, Miller recounts how he admired songs like The Power of Love by Jennifer Rush. “And,” says Miller, who recalls socialising with Nkoli at the Skyline Hotel, “he loved disco.”65

Gyre sees the Nkoli stage as a boundary-defying space, where the production can exist both as an opera and, simultaneously, as other things entirely: “It’s art that challenges conventions, which is what it needs to be”.66 His own rap interludes negotiate the tensions deliberately crafted between musical idioms; between social worlds; between then and now; and between what audiences might expect and some uncomfortable truths. Gyre sees them as a bridge: “a portal, drawing listeners through, explaining: this is what’s really happening.”67

Yet the production does not eliminate the thrilling emotion of solo arias. Diana Ross was mentioned in the prison letters; her 1980 I’m Coming Out Today, finds its counterpoint in Nkoli’s Coming Out is Not a Diana Ross Song.68

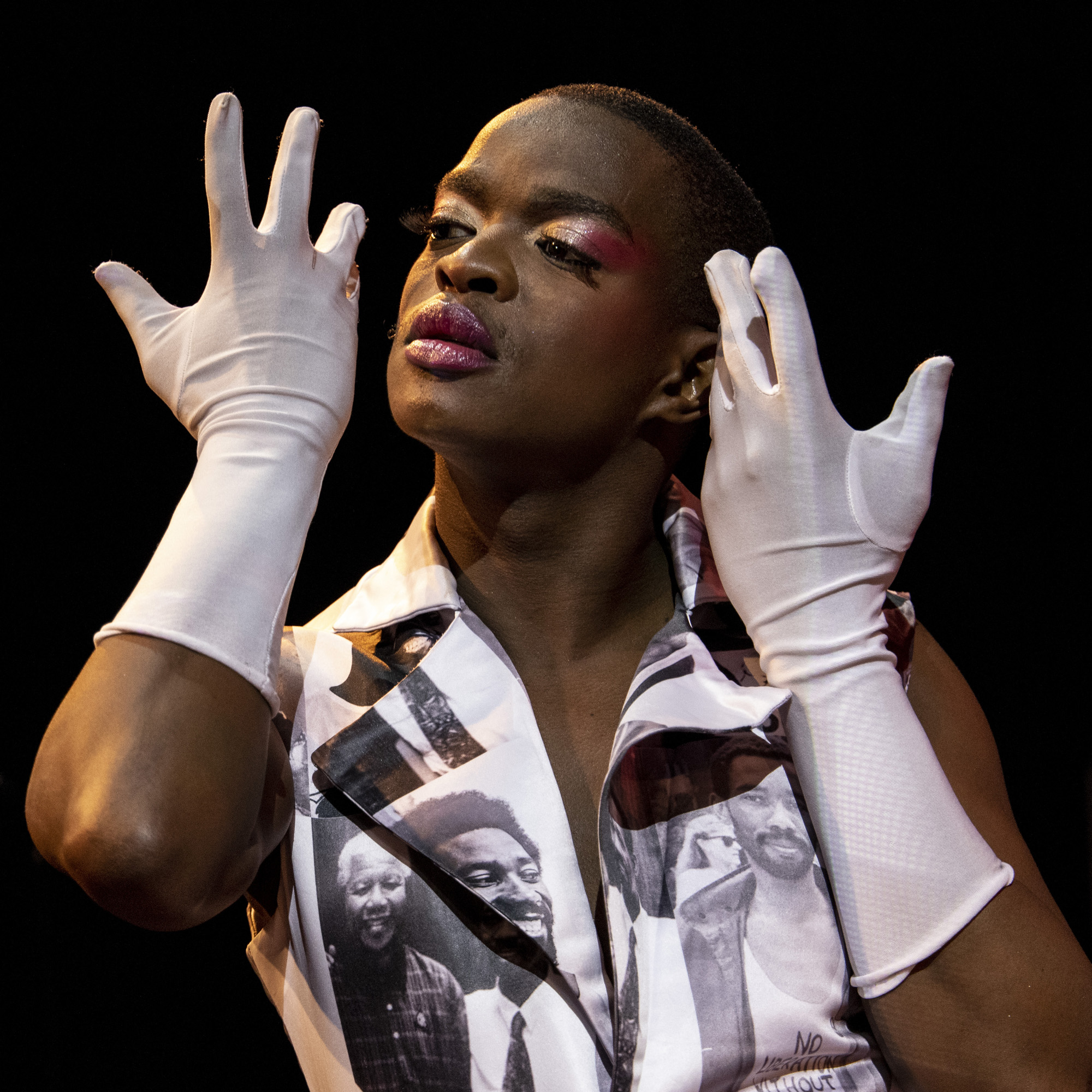

Perhaps the most moving aria is that sung by Nkoli’s mother, Elizabeth: Who Will Remember Me? It moves between recitative reflection and agitated melody. “As a child grows up/ they do things we do not know,” Masina sings, explaining her bewilderment (“I kept silent when you wore my clothes and shoes...”) on discovering her child was “a hermaphrodite/ a gay?!” and her equal bewilderment as Nkoli becomes a public figure that “I did not know you were so famous (...) they call me mother of the house/mother of the queer nation/ but what about me? (...)/They use my name without payment/ Ha re na madi (we have no money)”.69

That song, riffing on the terminology of both vogueing (“mother of the house”) and struggle (“mother of the nation”: the soubriquet awarded Winnie Mandela) emerged from deep, respectful conversations with Elizabeth Nkoli herself, part of a process of collective creation distant from the popular image of the classical composer locked away in his garret, writing an opera fuelled only by his lone genius. Miller and his team consulted many people around Nkoli: his family, his comrades in struggle, his Delmas legal team and more, and continued to consult with cast and crew and make changes during the years of the show’s development from workshopping and try-out, through other public iterations, to Market Theatre stage.70

Such collaboration has been Miller’s consistent working practice, and some of the Nkoli ensemble, such as Masina, have been his collaborators for many years. In 2023, reflecting on another production, he described how “often I will sketch some ideas and hand them over to a singer or musician to interpolate or improvise around. It is a conversation; a dialogue”.71

Musical director Tshegofatso Moeng cites collective teaching and learning as vital to shaping the whole character of the production: “Three of our cast members, including Siya Motloung, who plays Simon, are under 25. The popular music elements gave them points of reference – nobody didn’t know Brenda Fassie or Diana Ross – but they didn’t know Simon’s history. Philip created an atmosphere where they could learn, but also where anybody could say ‘I know it’s written like this, but can we try it like that instead?’”72

That chimes with Gyre’s experience. “I’d sung classical music, even Vivaldi, in my school choir. But when Philip sent through the actual beats, I was dumbfounded: No way! These are classical beats – I’m a pop artist: what do you want me to do with these? But as soon as we got into the studio together, we were almost finishing one another’s sentences! I was able to stay true to my intuition about what a musical or dramatic moment demanded, and say, for example, ‘I hear what needs to be said, but doing it this way is wack [wrong]! I can hear a bit of Amapiano in there, so...?’”73

“It was a porous process,” explains Miller. “There were massive debates in the constituency: about Simon’s misogyny [even about what the show should finally be titled]. My experience of Simon was only one experience and I had to remain conscious of that.”74

That ethos of respectful listening is in direct line of descent from the politics of people’s cultural structures during South Africa’s struggle era, paralleling the activist intention of this retelling of Nkoli’s story. Literary magazine Staffrider, for example, described in 1978 how: “A feature of much of the new writing is its ‘direct line’ to the community in which the writer lives. This is a two-way line. The writer is attempting to voice the community’s experience (‘This is how it is’), and his immediate audience is the community (‘Am I right?’)”.75 The approach was developed explicitly to guard against appropriation and to ensure that more privileged (for example, white) members of creative collectives neither assumed nor were ceded automatic authority.

The multivocality of the Nkoli process sounds in its music too. “Music has such emotional resonance,” says Miller. “We could tell the story employing classic vogueing categories – with a South African twist. So, for example, around the Delmas trial we had the ‘Carducci-suited lawyers’. But then we could have music that deliberately crashed against those ‘walking the runway’ types.”76

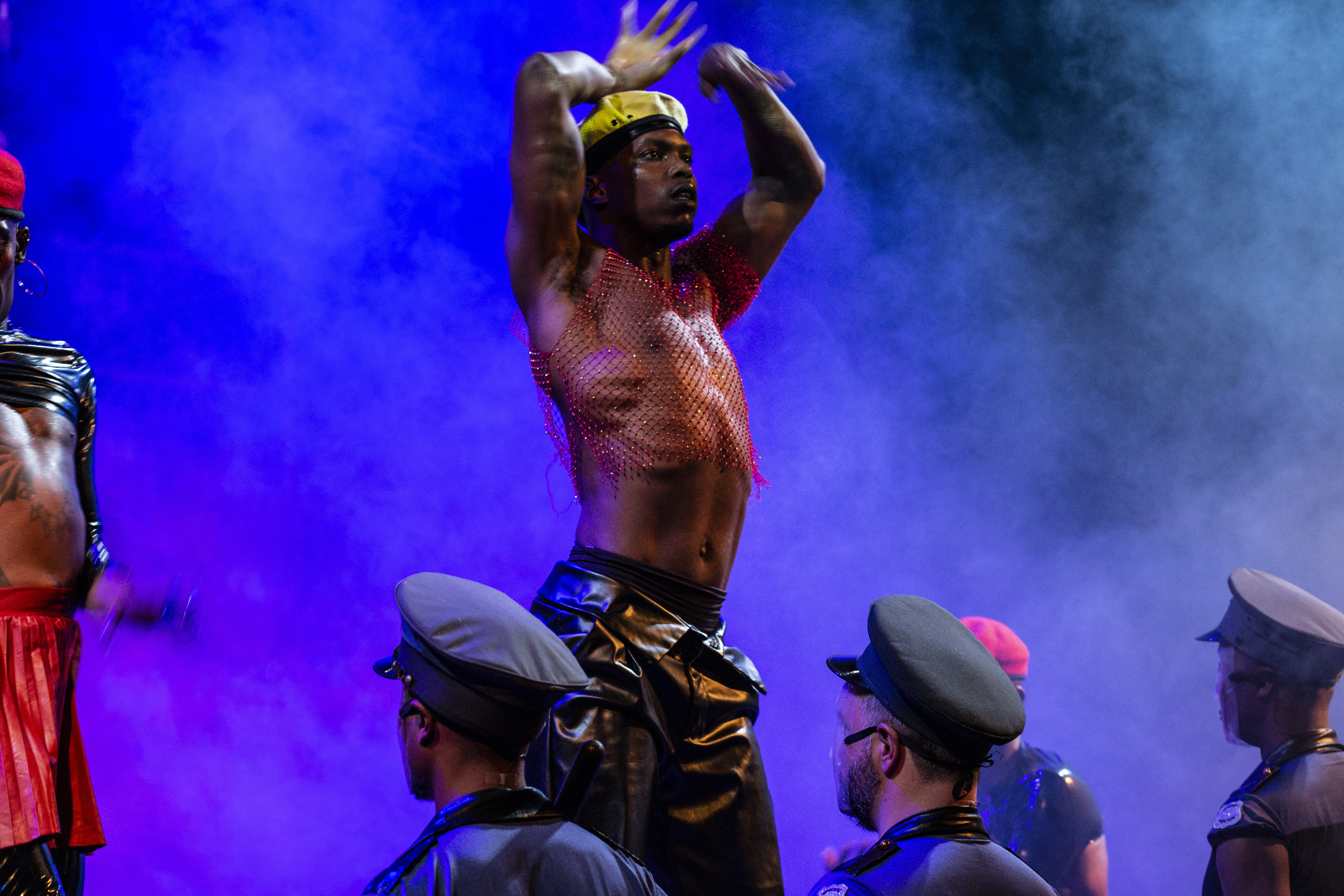

The “Carducci suits” form part of a complex staging vision, deliberately building on techniques of historic South African protest theatre as well as vogueing. Miller is emphatic about the major contribution of the work’s producer, Harriet Perlman, a veteran creator of activist film and television drama, as well as dramaturge Rikki Beadle-Blair, in melding these dramatic traditions. Working together, they conjured a stage vision that employs a catwalk ramp rather than a proscenium arch stage, and layers multimedia elements over the performed text of script and libretto. Campaign posters, newspaper headlines and relevant documents are projected above the stage, and, as in agit-prop, the audience is encouraged by the MC to offer spontaneous, loud responses, rather than maintaining reverent silence.

Costumes—not from a theatrical costumier, but from young Black queer stylist Mr Allofit—visually foreground the work’s African identity.77 Rather than the meticulous ethnographic accuracy of, for example, the Princess Magogo attire, the production wears a sharply contemporary mix of traditional print and ornament, outrageous vogue iridescence, and street style, echoing what younger audience members actually wear. The stage and catwalk are draped in pink glitter, the MC parades ballroom glamour; the cast in character wear re-visioned fashions and symbols of Nkoli’s era.78

“Using African prints and textures to create queer outfits,” says Gyre, “that’s decolonial! It frames the opera as an African story that just happens to be queer, just as Simon’s life was reflective of what was happening to Black people at the time – except he happened to be queer.”79 Nkoli himself had articulated that same intersectionality: “If you are Black and gay in South Africa,” he had said, “then it really is all the same closet...inside is darkness and oppression. Outside is freedom.”80

Each Nkoli ensemble member I spoke to expressed differently nuanced views about how the production challenged grand opera and how this related to decoloniality. For Beadle-Blair, for example, coloniality was challenged by the “synthesis – not pastiche – of diverse, including contemporary, music genres: reclaiming things from Africa. By drawing in music from the diaspora, it’s like a tree paying tribute to its leaves.”81 For Gyre, decoloniality rests in the overall project of “redirecting the lens through which we view anything away from a purely Western gaze.”82 The “vogue opera” form offered the best fit for the specificities of Nkoli’s human story: a buried legacy demanding reassertion in these times. But it simultaneously explored novel ways of speaking to potential new opera audiences about African histories, without centralising or naturalising the cultural tropes inherited from colonial conquest.

Nkoli weaves together and overlays multiple diverse elements to do this. By declaring itself a “vogue opera” – as Matshikiza did when he declared King Kong “a jazz opera”—the production claims space for work redefining what African opera can be, and who can be a hero. “In the bigger picture,” Miller says, “the resistance in the work lies in its creation of an activist campaign, primarily through social media, to tell Simon’s story.”83 In that frame, a catwalk that takes the stage physically into the midst of the audience is not only a vogue convention, but a hammer to smash the fourth wall.

“A Wonderful Performance by Innocent Masuku.” Westminster Abbey. Facebook. July 17, 2024. https://www.facebook.com/WestminsterAbbeyLondon/videos/a-wonderful-performance-by-innocent-masuku-tenor-who-sang-uxolo-peace-by-todd-ma/822379029861419/.

“About Joburg Theatre.” Joburg Theatre. https://www.joburgtheatre.com/about-us/.

“About Staffrider.” Staffrider 1, no. 1 (March 1978): 1.

Andrews, Jean. “Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine: French Grand Opera and the Iberian Exotic.” The Modern Language Review 102, no. 1 (2007): 108–24.

Ansell, Gwen. Soweto Blues: Jazz, Politics and Popular Music in South Africa. New York: Continuum Press, 2004.

Ansell, Gwen. “Mattera on Music in His Own Words.” Sisgwenjazz. July 19, 2022. https://sisgwenjazz.wordpress.com/2022/07/19/mattera-on-music-in-his-own-words/.

Ansell, Gwen. “Nkoli the Vogue Opera: The Making of a Musical about a Queer Liberation Activist in South Africa.” The Conversation Africa. November 16, 2023. https://theconversation.com/nkoli-the-vogue-opera-the-making-of-a-musical-about-a-queer-liberation-activist-in-south-africa-217833.

Balkis, Lale Babaoǧlu. “Defining the Turk: Construction of Meaning in Operatic Orientalism.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 41, no. 2 (2010): 185–93.

Ballantine, Christopher. Marabi Nights: Jazz ‘Race’ and Society in Early Apartheid South Africa. 2nd ed.

Scottsville, ZA: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2012.

Brukman, Jeffrey. “The White Claw Grabbing the Black Man’s Creative Work: Dominant Culture and African Expression, One Festival and Two World Premieres.” SAMUS: South African Music Studies Journal 38, no. 1 (2019): 261–88.

Ditsie, Beverly and Nicky Newman, directors. Simon and I. 2002; STEPS. 52 minutes. VHS.

Emmett, Melody. “Philip Miller Explores Power and Language as Form of Control and Oppression.” The Nollywood Reporter. May 18, 2023. https://thenollywoodreporter.com/theater/philip-miller-explores-power-and-language-as-form-of-control-and-oppression/#google_vignette.

Fleming, Tyler. Opposing Apartheid on Stage: King Kong the Musical. New York: University of Rochester Press, 2020.

Gershwin Blog Team. “Jazz Opera? Problems of Genre in Blue Monday.” The Gershwin Initiative. School of Music, Theatre & Dance, University of Michigan. January 28, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20241005193534/https://smtd.umich.edu//ami/gershwin?p=10784.

Heywood, Mark. “‘If Hamilton and RuPaul’s Drag Race Had a Baby in South Africa’—Icon Simon Nkoli Gets the Glamour Treatment.” Daily Maverick. November 15, 2023. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-11-15-icon-simon-nkoli-gets-the-glamour-treatment/.

Kester, Mabel. “South Africa’s Classical Music Ambassador who Made his Mark in Verdi’s Territory.” JamboAfricaonline. November 6, 2020. https://www.jamboafrica.online/south-africas-classical-music-ambassador-made-his-mark-in-verdis-territory/.

King Kong South Africa - A Reflection. The Fugard Theatre. Uploaded July 24, 2017. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-JOYA2Cn-4.

Madonna. “Vogue.” Official music video. Directed by David Fincher, 1990. Uploaded October 27, 2009. YouTube video, 00:04:33. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuJQSAiODqI&list=RDGuJQSAiODqI&start_radio=1.

“Medu Art Ensemble,” South African History Online, August 27, 2019. https://sahistory.org.za/article/medu-art-ensemble.

Meersman, Brent. “Winnie Faces the Music.” Mail & Guardian (South Africa). April 29, 2011. https://mg.co.za/article/2011-04-29-winnie-faces-the-music/

Mhlambi, Innocentia J. “The Question of Nationalism in Mzilikazi Khumalo’s Princess Magogo ka Dinizulu.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 27, no. 3 (2015): 294–310.

Miller, Philip. “Nkoli. The Vogue Opera.” Performed at the Baxter Theatre. October, 2024. Uploaded December 2, 2024. YouTube video, 00:05:22. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJCD7Y9qJXo.

Molefhe, Z. B. and Mike Mzileni. A Common Hunger to Sing: A Tribute to South Africa’s Black Women of Song, 1950–1990. Cape Town: Kwela Books, 1997.

Moore, Matt. “Diana Ross Originally ‘Didn’t Understand’ how I’m Coming Out was a Queer Anthem.” Gay Times. May 24, 2020.

https://www.gaytimes.com/culture/diana-ross-originally-didnt-understand-how-im-coming-out-was-a-queer-anthem/.

Morgan, Thaddeus. “How Nineteenth Century Drag Balls Evolved into House Balls, Birthplace of Vogueing.” History.com. June 28, 2021. https://www.history.com/articles/drag-balls-house-ballroom-voguing.

Msibi, Thabo. “The Lies We Have Been Told: On (Homo) Sexuality in Africa.” Africa Today 58, no. 1 (2011): 55–77.

Muller, Wayne. “A Reception History of Opera in Cape Town: Tracing the Development of a Distinctly South African Opera Aesthetic (1985-2015).” PhD diss., University of Stellenbosch, 2018.

Muller, Wayne. “Opera in Africa: Critics Trace how a Colonial Art Form was Reinvented as African.” The Conversation Africa. November 29, 2023. https://theconversation.com/opera-in-cape-town-critics-trace-how-a-colonial-art-form-was-reinvented-as-african-217698.

Ntsabo, Mihlali. “Meet Gyre, the Rapper Driving a Queer Revolution.” Mambaonline.com. February 21, 2019. https://www.mambaonline.com/2019/02/21/meet-gyre-sa-the-rapper-driving-a-queer-hip-hop-revolution/.

Olwage, Grant. “Apartheid’s Musical Signs.” In Composing Apartheid: Music for and Against apartheid, edited by Grant Olwage. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2008, 35–53.

Porter, Eric. What is This Thing Called Jazz? African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Pyper, Brett. “State of Contention: Recomposing Apartheid at Pretoria’s State Theatre 1990-1994. A Personal Recollection.” In Composing Apartheid: Music for and against apartheid, edited by Grant Olwage. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2008, 239–53.

Rocha, Esmeralda M. A. “Imperial Opera: The Nexus Between Opera and Imperialism in Victorian Calcutta and Melbourne 1833-1901.” PhD diss. University of Western Australia, 2012.

Roos, Hilde. “Indigenisation and History: How Opera in South Africa became South African Opera,” Acata academica supplementum 1 (2012): 117–55.

Roos, Hilde. “The Eoan Group and Opera in the Age of Apartheid.” UC Press Blog. October 31, 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20240214100152/https://www.ucpress.edu/blog/39360/the-eoan-group-and-opera-in-the-age-of-apartheid/.

Said, Edward W. Culture and imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

“Simon Nkoli.” South African History Online. July 25, 2025. https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/simon-nkoli.

This is Amapiano: Director’s Cut BBC Africa. BBC News Africa. Uploaded August 20, 2022. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ou0luMrf1mU.

Tucker, Percy. Just the Ticket. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 1997.

van der Hoven, Lena. “Opera has been Dying Slowly Even before Covid-19: Mapping South African Opera after 1994.” SAMUS 41-42 (2021/2022): 256–93.

Vokwana, Thembela. “The Empire Sings Back: The Deep History behind South African Soprano Pretty Yende’s Triumph.” The Conversation Africa. December 6, 2024. https://theconversation.com/the-empire-sings-back-the-deep-history-behind-south-african-soprano-pretty-yendes-triumph-205152.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.